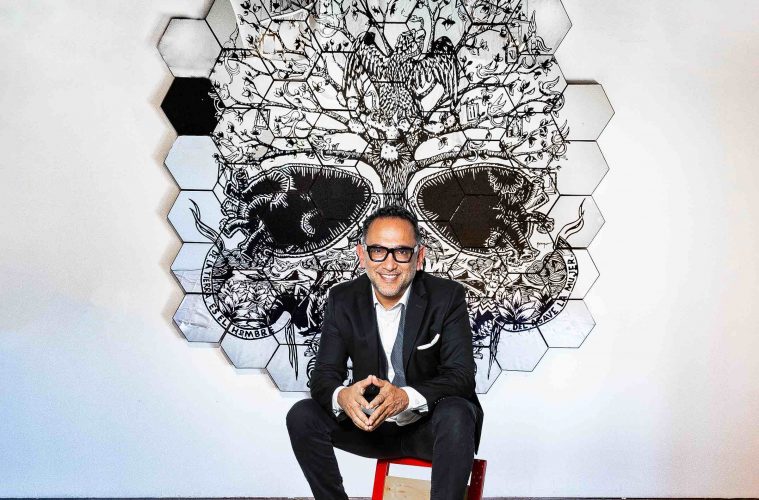

For Gennaro Garcia, art is all around us, from the clothes we wear to the buildings we live in to the food – and tequila – we consume. Whether he’s designing murals for restaurants or leading tours of his studio for students, Garcia tirelessly spreads his gospel of creativity. His paintings, prints, ceramics, and woodwork grace the walls of three-star Michelin restaurants, nearly a dozen prestigious galleries spread across two countries, and the homes of collectors, where they even hang beside the works of his main inspiration, Frida Kahlo.

Garcia also owns restaurants, counting a string of celebrity chefs as his friends and partners. In a time when walls have become lenses exposing America’s underbelly, Garcia shows that the Mexican and American dreams can share a border and a table, making all our lives a little happier and more colorful for it.

Growing up poor in Mexico, for Garcia, creativity was a part of daily life. When he wanted toys, Garcia and his father made them out of whatever materials were available. As a teen in San Luis – a Mexicantown across the border from Yuma – he painted signs for local businesses and helped his dad run restaurants. He honed the DIY ethos and down-to-earth style that are as much his trademarks as Tzompantli skulls and outstretched hands. He studied graphic design at a university in Tijuana and then returned to San Luis to take over his father’s restaurant, after the rest of the family moved to Yuma.

Growing up poor in Mexico, for Garcia, creativity was a part of daily life. When he wanted toys, Garcia and his father made them out of whatever materials were available. As a teen in San Luis – a Mexicantown across the border from Yuma – he painted signs for local businesses and helped his dad run restaurants. He honed the DIY ethos and down-to-earth style that are as much his trademarks as Tzompantli skulls and outstretched hands. He studied graphic design at a university in Tijuana and then returned to San Luis to take over his father’s restaurant, after the rest of the family moved to Yuma.

Continually trading up from a small food cart to a larger one to an actual storefront, Garcia noticed that field workers a few hundred meters north in the U.S. were making more than he was as a restaurant owner. Like so many young and ambitious immigrants before him, he came to America with a dream and little else. Broke and with no connections, he slept in an alley for the first few weeks while he found a job and place to live.

Later, Garcia painted murals on the walls and ceilings of the modest house his family rented. He took photos, to show local restaurant owners what he could do. Though at first he had no takers, Garcia eventually received his first commission to paint a mural for Mi Ranchito Restaurant in Yuma, where his art still graces the walls. Within two months of starting the project, he was hired as the restaurant’s general manager, a job he kept for five years.

“The owner is like my second dad,” Garcia recalled. “His son was the best man at my wedding years later.”

Garcia eventually met Briseida, an ASU student visiting Yuma. They quickly fell in love. After a few months, he moved to Phoenix and worked as a manager at a Mexican restaurant. Two years later, he told Briseida that he wanted to do art full-time. She encouraged him to pursue his dream, helping him to weather the drop in his income during the transition.

“I think that’s something every artist needs, somebody that gives them support,” Garcia said.

Garcia quit his day job and began painting at a furious pace, then working in a highly abstract style. In Ahwatukee, where he and Briseida still live, he found a coffee shop that let him display his art. A woman who liked what she saw contacted him, explaining that she ran a high-end interior design company and offering him a job doing what he loved: painting. Garcia honed his craft and style, working first as an apprentice and eventually as senior muralist. After five years, Garcia sold his stake in the company and finally married Briseida. He was ready to court the art world in a big way.

His first gallery show was with Xico Arte y Cultura, now known as Xico Inc., whose mission is to “nourish a greater appreciation of the cultural and spiritual heritages of the Latino and Indigenous peoples of the Americas throughout the Arts.”The organization operates galleries at their headquarters on Buckeye Road as well as the container complex on Roosevelt Row. It was through Xico that Garcia first connected with Virginia Cardenas, who was on the nonprofit’s board. Virginia and her husband Jose are prominent local art collectors and supporters of Latino culture. Garcia resolved to see his works enter their extensive collection. He developed a friendship and deep admiration for the couple.

“They used to come and see my art at festivals and galleries,” Garcia recalls. “They loved the art, but it took them two years to get one of my pieces.”

Now six of his works grace the walls of the couple’s home, which Jose preserves in honor of Virginia – she died of kidney cancer in 2012. One of Garcia’s next big breaks came with a show at Calvin Charles Gallery in Scottsdale. Things went well, and he began lobbying hard for a solo show, which he got a few months later. At the time, he was only the second Latino to do so there. Knowing how vital the show’s success would be for his career, Garcia poured his own money and energy into promoting it, even taking out full-page ads in magazines. His efforts paid off: the show sold well and launched Garcia into a higher stratum of the art world.

“After that one, most galleries came easily,” Garcia recalls.

Garcia had also begun working with prominent spaces in Los Angeles, such as ChimMaya Gallery, an East L.A. fixture for up-and-coming Latino artists since 2005. At long last, he was achieving the success he had pursued for years. A gallery from New York reached out about doing a show there, and Garcia said yes. During a family celebration afterward, his father congratulated him on finally achieving his “American dream.” The comment lodged in Garcia’s head, leading him to deep introspection and precipitating something of an artistic crisis.

Garcia had also begun working with prominent spaces in Los Angeles, such as ChimMaya Gallery, an East L.A. fixture for up-and-coming Latino artists since 2005. At long last, he was achieving the success he had pursued for years. A gallery from New York reached out about doing a show there, and Garcia said yes. During a family celebration afterward, his father congratulated him on finally achieving his “American dream.” The comment lodged in Garcia’s head, leading him to deep introspection and precipitating something of an artistic crisis.

“I was talking to my wife the next day and told her, ‘Seriously, what happened to my Mexican dream?’” Garcia recalls. “I’m about to have the show of my life in New York, but nobody knows my name in Mexico.”

Unable to dislodge the demon of doubt, Garcia made the bold move of cancelling the show. He had recently met and befriended Carlos Muñoz, a film director from Mexico City, whom he told about his decision one night while they shared tequila. “Ohpendejo,that’s stupid,” Garcia recalls his friend saying before breaking into a self-effacing laugh. However, Muñoz also understood Garcia’s desire to be true to his roots. He eventually accompanied the artist and filmed him as he journeyed across Mexico in search of gallery representation in his homeland.

Garcia set his sights on San Miguel de Allende, drawn by the city’s unique history and beauty. Located in the central Mexican state of Guanajuato, San Miguel de Allende has a history of attracting artists from around the world, and was recognized as a UNESCO world heritage site in 2008. A friend and art collector he knew there took Garcia and Muñoz around town, introducing the artist to numerous gallery owners.

After a series of rejections, the indefatigable Garcia finally found a gallery space. He carted his art across the border, and the show proved to be a critical and commercial success. After the show, when Garcia picked up the remaining items, a local art collector – who had acquired five trunks of art, journals, and other property purportedly belonging to Frida Kahlo (though its authenticity has been hotly disputed) – acquired Garcia’s remaining works. His gambit had paid off.

Garcia continued to work in the U.S. at the same time, adopting a border-straddling existence he continues to this day, traveling between the two countries at least ten times each year for various art and business projects. Like his life, Garcia’s art fuses elements from both of the countries he calls home, as well as his twin passions of food and art.

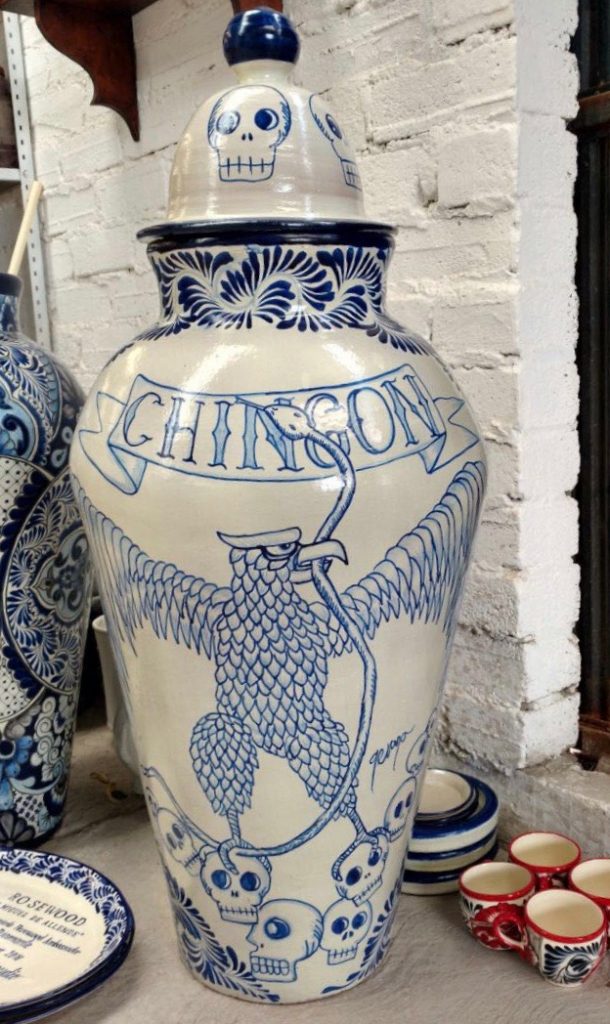

One example of this is his Hecho A Mano ceramics collection, which features a pair of open palms as the primary visual motif – sometimes connected to wrists tattooed with birds, webs, and roses – representing the way his parents worked with their own hands to feed Garcia and his siblings. After Marcela Valladolid, a chef famous for her show on the Food Network, posted images of the plates to her social media accounts, Garcia saw orders on his web store skyrocket overnight.

Garcia also began to study and collaborate with Mexican artists and craftsmen in the city of Pueblo, learning the city’s colorful tradition of Talavera ceramics, which he used to create a mosaic for the Four Seasons Resort in Scottsdale.

Another transnational endeavor is Garcia’s work with chef Javier Plascencia, who helped Baja California become a mecca for foodies and wine aficionados from across the globe. In a business mashup worthy of the hippest urban enclaves in the U.S., the two are opening an art gallery/butcher shop.

With plans to house the hams, chorizos, and other locally made artisan meats within a glass cube inside the space, Garcia explains that the project’s heart is two friends sharing their respective arts in one place. The shop will share a property with Plascencia’s Animalon, a dining experience located under a hundred-year-old oak tree, and Finca Altozano, another of the chef’s world-class restaurants.

A little north of Baja, in La Jolla, California, Garcia has worked with George Hauer and Trey Foshee on both George’s at the Cove and Galaxy Taco, another pair of famous restaurants. The latter establishment invited Garcia to dust off his chef’s hat and participate in its Taco Takeover event, where a visiting chef (or artist/chef) occupies the kitchen for an evening.

Garcia was somewhat reluctant at first, afraid his cooking skills were rusty, but luckily Aaron Chamberlin, a prominent Phoenix chef and restaurateur previously profiled in JAVA, volunteered himself and Suny Santana to tag along for a road trip and guerilla-cooking expedition to California. On the way home, the trio discussed their love for the taco, a conversation that spurred them to partner in the creation of Taco Chelo on Roosevelt Row in Phoenix.

Garcia “is one of the best marketers I know,” Chamberlin said of his friend and business partner. “He knows everybody, and that’s because of his passion for food. He understands food, and he understands restaurants. Another thing about Gennaro that makes him unique from the art perspective is that he’s very fast. When you’re in the restaurant business, you need everything two weeks ago. Those are the things that make him unique and relevant to restaurants and why he gets work through so many chefs.”

Garcia currently splits his time about 50/50 between his design work – collaborating with everything from fashion labels to wineries and tequila distilleries – and studio art, juggling a staggering number of projects that keep him constantly on the go. While you might think this lifestyle could pose challenges for the father of a nine-year-old daughter (who, of course, is named Frida), the pair share a passion for art and Disney. Though Frida is still in elementary school, her own work has been featured in a half-dozen gallery shows, and it has sold well, as Garcia – her first collector and biggest fan – is quick to point out.

Garcia currently splits his time about 50/50 between his design work – collaborating with everything from fashion labels to wineries and tequila distilleries – and studio art, juggling a staggering number of projects that keep him constantly on the go. While you might think this lifestyle could pose challenges for the father of a nine-year-old daughter (who, of course, is named Frida), the pair share a passion for art and Disney. Though Frida is still in elementary school, her own work has been featured in a half-dozen gallery shows, and it has sold well, as Garcia – her first collector and biggest fan – is quick to point out.

During a night of dining with a group in California, one of the guests asked Garcia if he would be willing to discuss how he integrates creativity into parenting in front of a crowd, for a nice paycheck. Somewhat incredulous at first, Garcia finally understood when a friend explained that the man was vice president for Disney’s Latin American and Caribbean operations. Garcia accepted, and Disney footed the bill to fly him and his family to Mexico City, where he and Frida gave a presentation to a rapt crowd of Disney executives and creatives.

When Frida was asked who her favorite princess was, she said she didn’t like princesses, but preferred the heroines from the Disney series “The Descendants,” which follows the younger relatives of some of the company’s most infamous villains. This led to her and her father flying to Mexico City again, where they created a mural to promote the film. In classic style, Garcia invited local graffiti artists to participate as well. As always, Garcia was acting as a bridge, this time between the rough-and-tumble world of Mexico City street art and one of the world’s largest entertainment companies.

Garcia points to his own life as an example of the contributions immigrants can offer. For him, the border is a cultural crossroads, not a place for hate or lies. Ever sensitive to his surroundings, he laments the “visual contamination” that barriers on the border impose on communities along both sides. Now, his art literally helps block such aesthetic imperialism. In 2015, San Luis installed a series of 30 billboards featuring Garcia’s art in front of the metal barrier running along the border. Like his other projects, it embodies his commitments both to building community through art and infusing creativity into daily life.