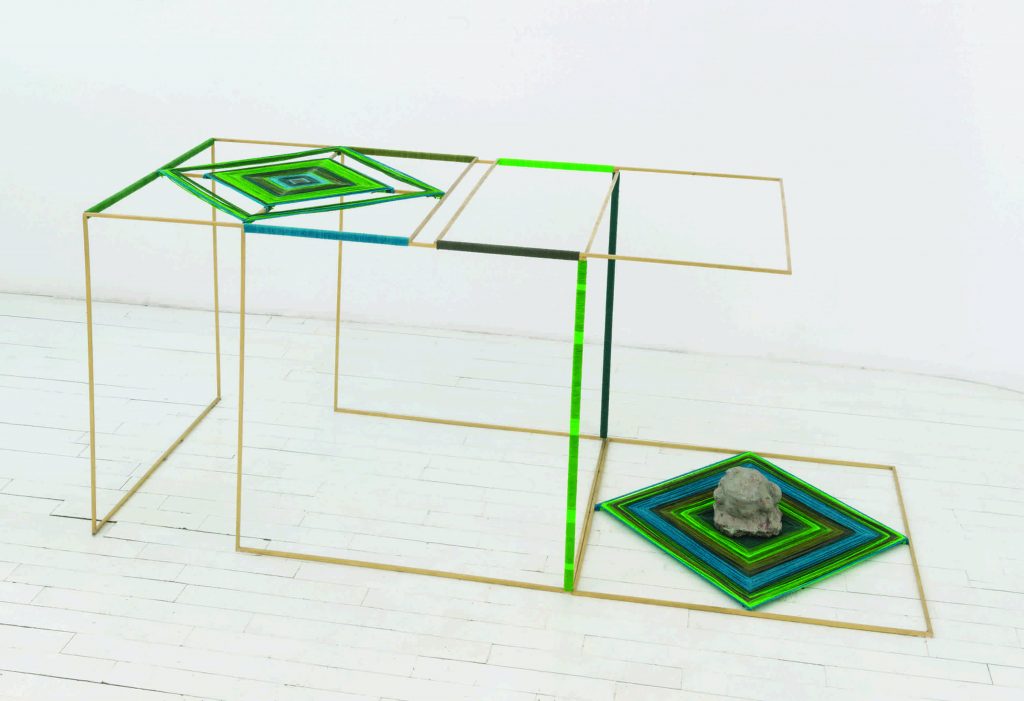

Claudia Peña Salinas, “Cueyatl,” 2017, Brass, dyed cotton, concrete frog, 24 1/2 x 24 x 61 inches, Collection of Ignacio Lopez & Laura Guerra, Photo by Adam Reich, Courtesy of the artist and Embajada, San Juan.

Over the past several years, artist Claudia Peña Salinas has narrowed the focus of her practice to two Aztec water deities: Tláloc and Chalchiuhtlicue. Her research into the subject is as much personal as it is political. Peña Salinas was born in Montemorelos, Mexico, and now lives and works in New York City. The pursuit of this particular body of work has led her all around Mexico: from major sites including the National Museum of Anthropology and Teotihuacan to street markets and tourist shops. What results is a series of works – sculpture, photography, and video – that transform the didactic into the poetic and problematize the ways in which images construct national identity.

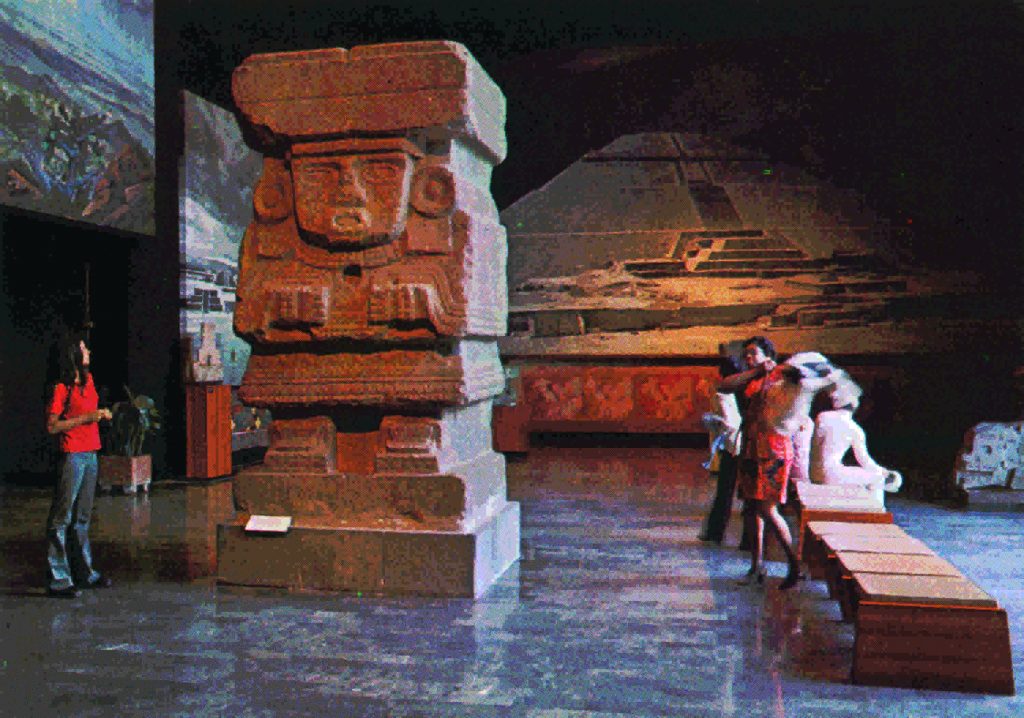

Her work unfolds as a sort of travelogue that compresses past and present, vernacular and sacred. Tlachacan, the earliest work in the exhibition, is an informative video essay that follows the artist as she searches for the original site of the Tláloc monolith, which now sits transplanted at the entrance to the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. Over the course of her research and travel, the artist uncovers replica upon replica that span the gamut of image economies: decorative facsimiles erected throughout the country, souvenirs and memorabilia sold to tourists, and images found online. As a documentary, the video presents a history of this monolith, but it’s more aptly laid out as a history of its misuse.

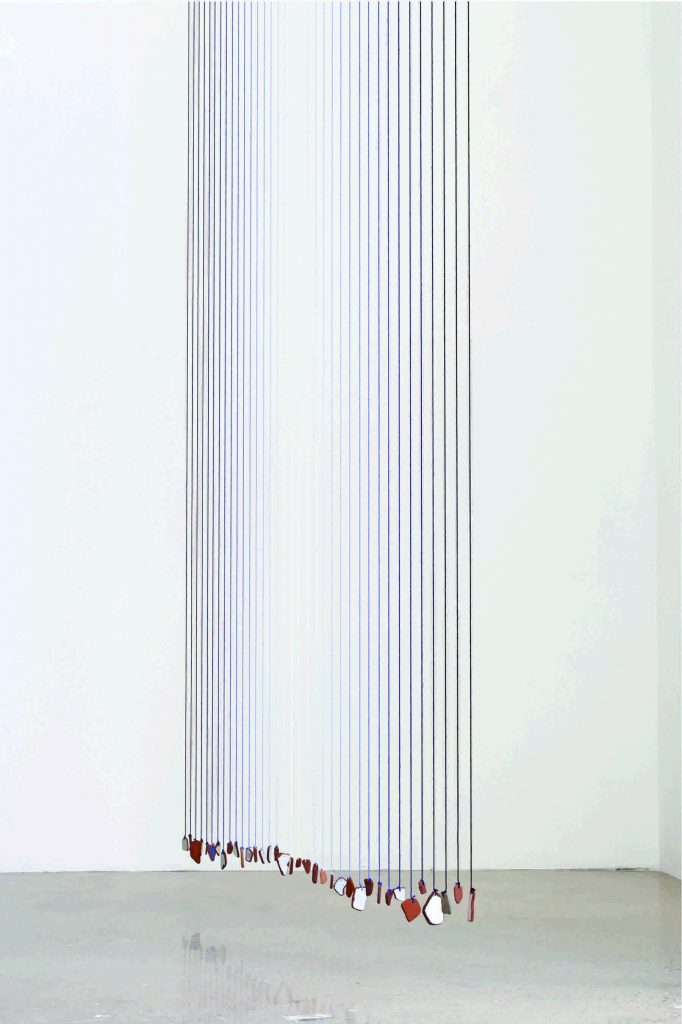

Claudia Peña Salinas, “Acapulco Blue,” 2018, Brass, dyed cotton, obsidian, ceramic, metal, plastic and wood

The artist’s investment in the circulation of these images is compellingly spiritual, as if she is searching not only for the aura of the original but for a part of her ancestry outside of constructs such as nationality, class, and gender. We learn, though, as the video goes on, about the water crisis in Mexico, about the country’s plan to build a hypermodern airport atop a depleted lake, and about how this project presents a threat to the ecosystem, archaeological sites, and landowners.

At one point in the final section of the video, Peña Salinas shifts focus to an image of a stone statue in the National Museum of Anthropology that appears on a postcard. “It is attributed to Chalchiuhtlicue, the goddess of terrestrial waters, of rivers, lakes, and springs,” the video reads. “In this postcard from the 1970s it is labeled as Tláloc.” The image, which reappears throughout the artist’s work and is presented in the adjacent gallery alongside her sculptures, speaks to how slippery history can be and how our understanding of it is inevitably shaped by modernity.

Claudia Peña Salinas, “Tlaloc,” 2016, Brass, Inkjet monoprint on wax panel, 24 x 36 inches,

Courtesy of the artist and Embajada,

Where Tlachacan sharply traces its subject through a highly rational approach that still manages to weave together autobiographical narrative with documentary, Metzilocan, the artist’s latest video work, from which the exhibition takes its name, represents a liberation from form. Taking a definitively non-narrative approach, the video focuses on the figure of Chalchiuhtlicue and the Nahuatl words for water (atl) and moon (metztli). The sequence of images, clips, and text – of the Chalchiuhtlicue statue, the Pyramid of the Moon at Teotihuacan, and lush landscapes with picturesque waterfalls – is accompanied by an eerie, otherworldly score that layers distorted recordings of water with sounds produced using turtle shells and other pre-Hispanic instruments.

The video relies heavily on the associative traits of montage, a gesture that reverberates throughout the exhibition. The artist’s sculptures, which refer to motifs of mythology, are arranged as a compound through which we navigate. Level with the floor on either end of the gallery are two large reproductions of photographs of the Chalchiuhtlicue statue exhibited in the museum. Displayed in geometric brass enclosures, Peña Salinas’s objects appear as artifacts outside the context of history. They instead represent a kind of potentiality, a possibility of what we don’t already know – the very thing that drives modernity. Peña Salinas has, in effect, rearranged the tableaux of history to reflect the reciprocity of “then” and “now.”

One of the main concerns this exhibition raises is whether it is possible to preserve without erasure. The figures and symbols that Peña Salinas references in her work have traveled far from the context of their ancient city, and have traveled even further as reproducible images and decorative replicas. Deposed in the space of the museum, they become emblems, not of the gods themselves, but of conquest and progress. Metzilocan asks us to approach history not as a lateral timeline but as a set of layers to maneuver through. The forward stroke of the contemporary doesn’t mean that we have to abandon looking back.

Metzilocan

Through August 3

ASU Art Museum

asuartmuseum.asu.edu

An extension of “Metzilocan” is also on view at the Innovation Gallery at the School of Human Evolution and Social Change.