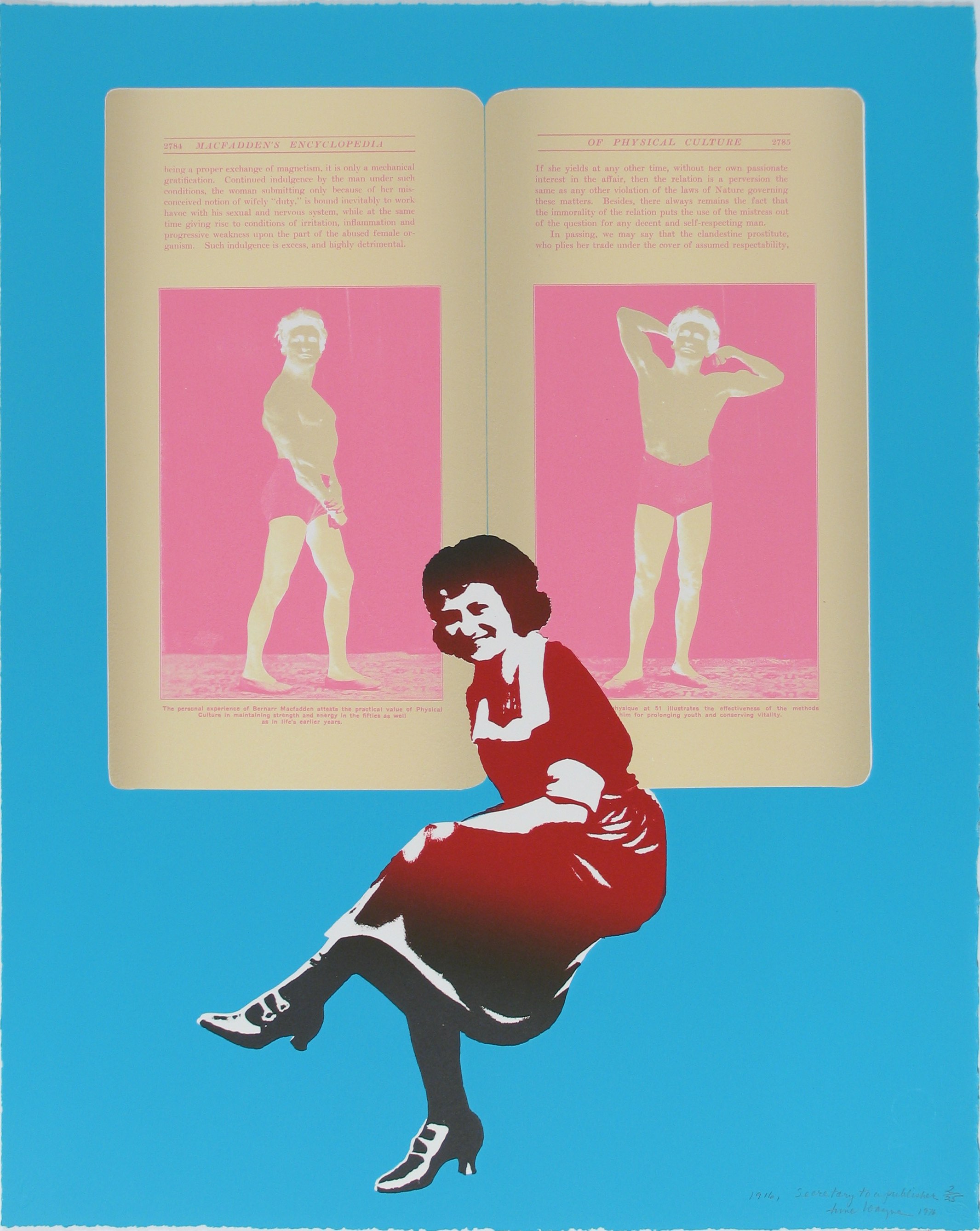

June Wayne, “Secretary to a Publisher (Plate 6 of the Dorothy Series),” 1976, lithograph, 17 x 1/4 x 21 1/2 inches, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Malcolm Dorfman

Too often, museums rely on a narrowing repertoire of artists with obvious oeuvres to draw a crowd. Kusama, Kapoor, Hirst, Judd, Turrell – these are artists whose works are so recognizable that every museum makes sure to have at least one of each. The ASU Art Museum’s current show about the under-recognized life and artistic practice of June Wayne (1918–2011) is a welcome contrast. Brief but delightful, Change Agent: June Wayne and the Tamarind Workshop exhibits seldom-seen prints from the museum’s permanent collection by an artist whose multifaceted practice extended far beyond her role as a maker of objects.

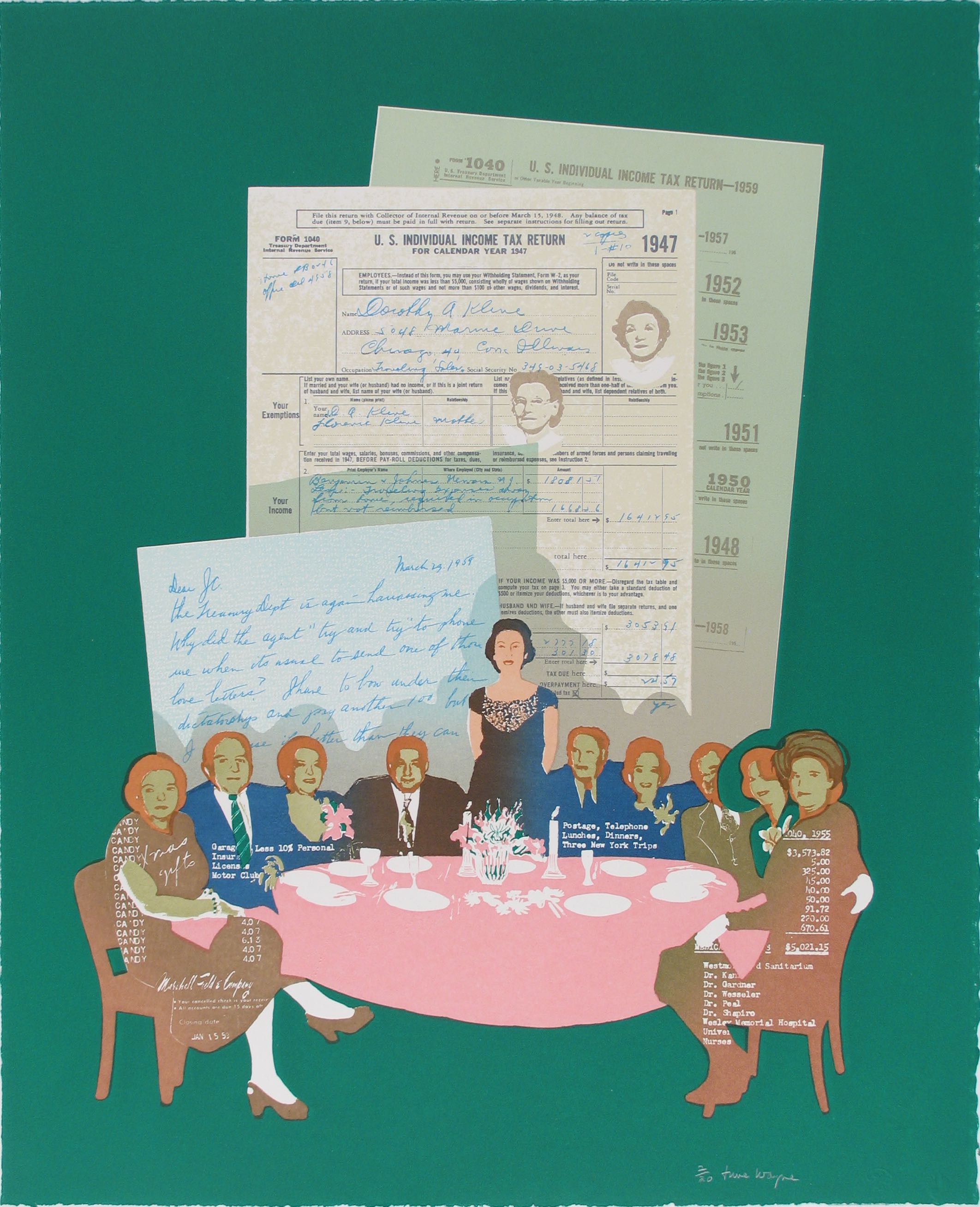

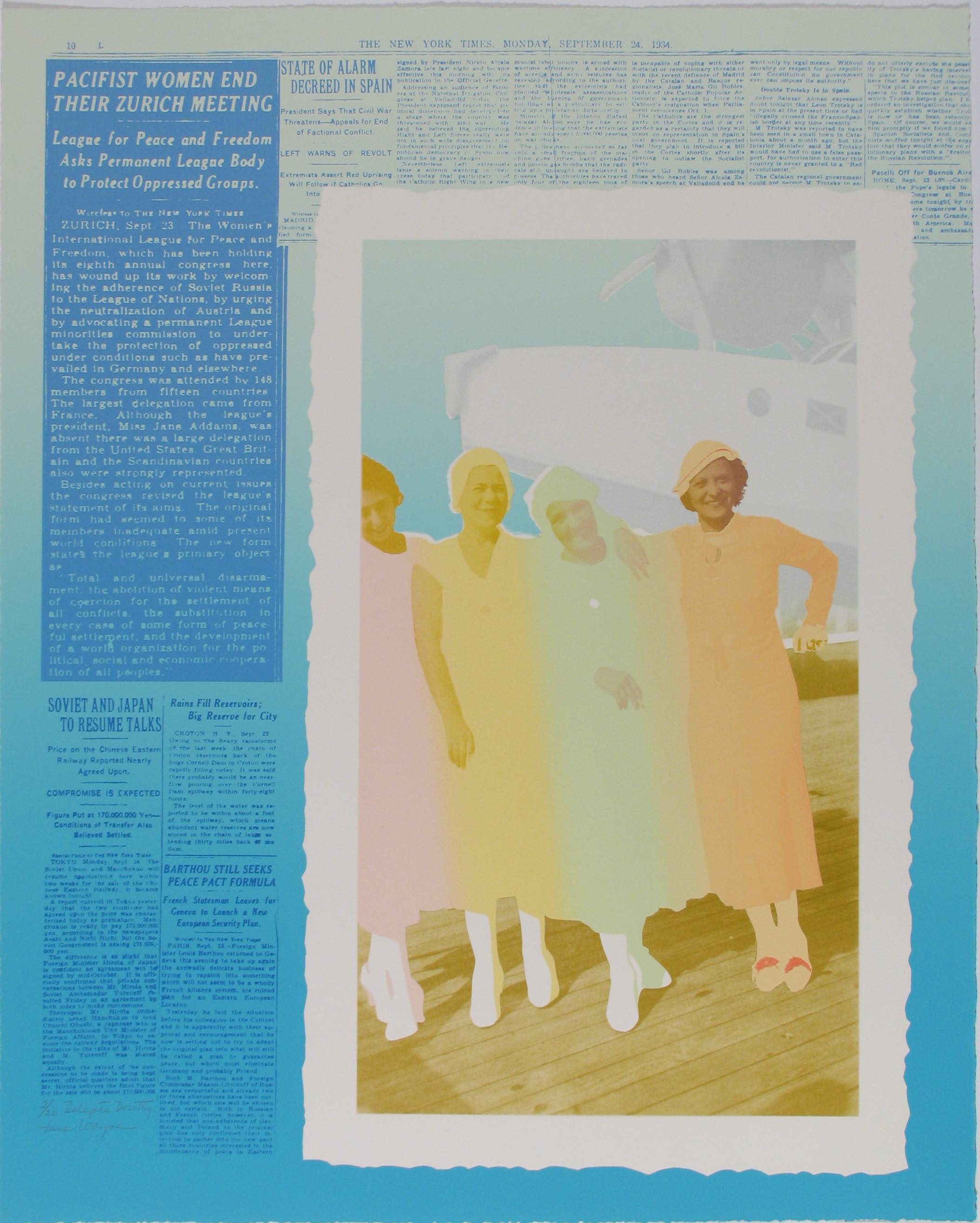

The exhibition lays out the life of June Wayne and her artistic practice chronologically in three parts. The first room begins with Wayne’s earlier works in which she looks back toward her childhood in early 1900s Chicago and the working women she grew up with. She tells these stories with wild and unrestrained technical proficiency, combining figurative painting, photo collage, and saturated color gradients.

June Wayne, “Dorothy and the IRS (Plate 17 of the Dorothy Series),” 1978, lithograph, 17 1/4 x 21 1/2 in., Gift of Dr. & Mrs. Malcolm Dorfman

Several prints are from the “Dorothy” series, in which Wayne explores the life of her mother as a Russian immigrant, working-class woman, and single parent. In Winter of ’37 (1979), a photocopy of Dorothy’s social security card and a silver-plate negative of an embroidered glove float on a yellow-blue color field. The gradient transitions into an ambiguous color in between this document of citizenship and the glove. The prints in this first room are the most emotionally resonant in the show. Wayne overlaps historic iconography with personal biography in a way that’s totally refreshing and eye-opening.

The second set of prints follows Wayne in the ’70s and ’80s, when she lived in L.A. near Caltech and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Wayne made fast friends with members of the scientific community who were discovering a new cosmic view of the universe. With intimate insight into this scientific research, Wayne depicted an astral and physical way of seeing the world that succeeds in offering a poetic reaction rather than an illustrative derivation. In these prints, Wayne focuses on light and texture, leaving behind any sense of the human scale or figure-ground organization. Viewed next to her earlier prints, one would not recognize these as from the same artist. Wayne demonstrates – without apologies or rationalizations – her ever-evolving technical style and the freedom with which she approached her own career.

June Wayne, “Winter of ’37 (Plate 12 of the Dorothy Series),” 1979, lithograph, 17 1/4 x 21 1/2 inches, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Malcolm Dorfman

At the time Wayne was an artist, printmaking and lithography in the United States was considered a reproduction technique for more legitimate mediums, and not a creative practice in its own right. In Paris, where Wayne sought an apprenticeship, the European tradition of creative lithography remained. Wayne brought back this independent form of artistic practice and began teaching classes in printmaking, focusing particularly on empowering women artists. With a grant from the Ford Foundation, Wayne founded the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in 1960, which remains one of the strongholds of printmaking pedagogy and printmaking research to this day. It is as a teacher and educator, particularly of women, that Wayne is best remembered.

The third and final set of lithographs is dedicated to Wayne’s lasting legacy: the Tamarind Institute and its students. These prints are by students of the workshop and further diversify the expansive visual vocabulary of the show with unique contributions. It’s proof of Wayne’s mastery as a craftsperson and an artist that her teaching was effective for so many people – including more celebrated names than her own, such as Ed Ruscha, Richard Diebenkorn, and Joseph Albers. But it’s also striking that while Wayne fostered a generation of printmakers and built institutional networks, her own work as a printmaker has largely escaped recognition.

June Wayne, “Delegate Dorothy (plate 11 of the Dorothy Series),” 1977, lithograph, 21 1/2 x 17 1⁄4 in., Gift of Dr. & Mrs. Malcolm Dorfman

June Wayne’s work forms a deeply fascinating collection, especially in the context of a teaching institution such as ASU Art Museum. The museum makes her prints and the works she printed by other artists available as a teaching resource, while also preserving them as physical objects. What is most compelling for contemporary artists and students, however, are aspects of Wayne’s practice beyond preservation: the way she formed her artistic career. She was of the same generation as artists who were employed by the WPA program and experienced the rise of American Abstract Expressionism in a growing art market – dominated then by names that are canonical today: Reinhardt, de Kooning, Pollock.

June Wayne, “Solar Flame (from Solar Flares suite),” 1982, lithograph, 16 1/8 x 16 in., Gift of Dr. & Mrs. Malcolm Dorfman

Wayne pushed back against market pressure that encouraged artistic products that were recognizable, attributable, and collectable. In contrast to many well-known artists who were her contemporaries, her career was chimeric, often centered on collaboration or a shared platform, and thus difficult to assign market value. The pressure Wayne experienced to conform to certain ideas of what constitutes valuable cultural and artistic production is all the more intense today. For contemporary artists – and art students graduating from ASU – June Wayne’s choices and her resulting body of work help expand what we should consider as the scope of an artist’s work.

Change Agent: June Wayne and the Tamarind Workshop

June 1, 2019 – January 25, 2020

ASU Art Museum

51 E. 10th Street, Tempe

www.asuartmuseum.asu.edu