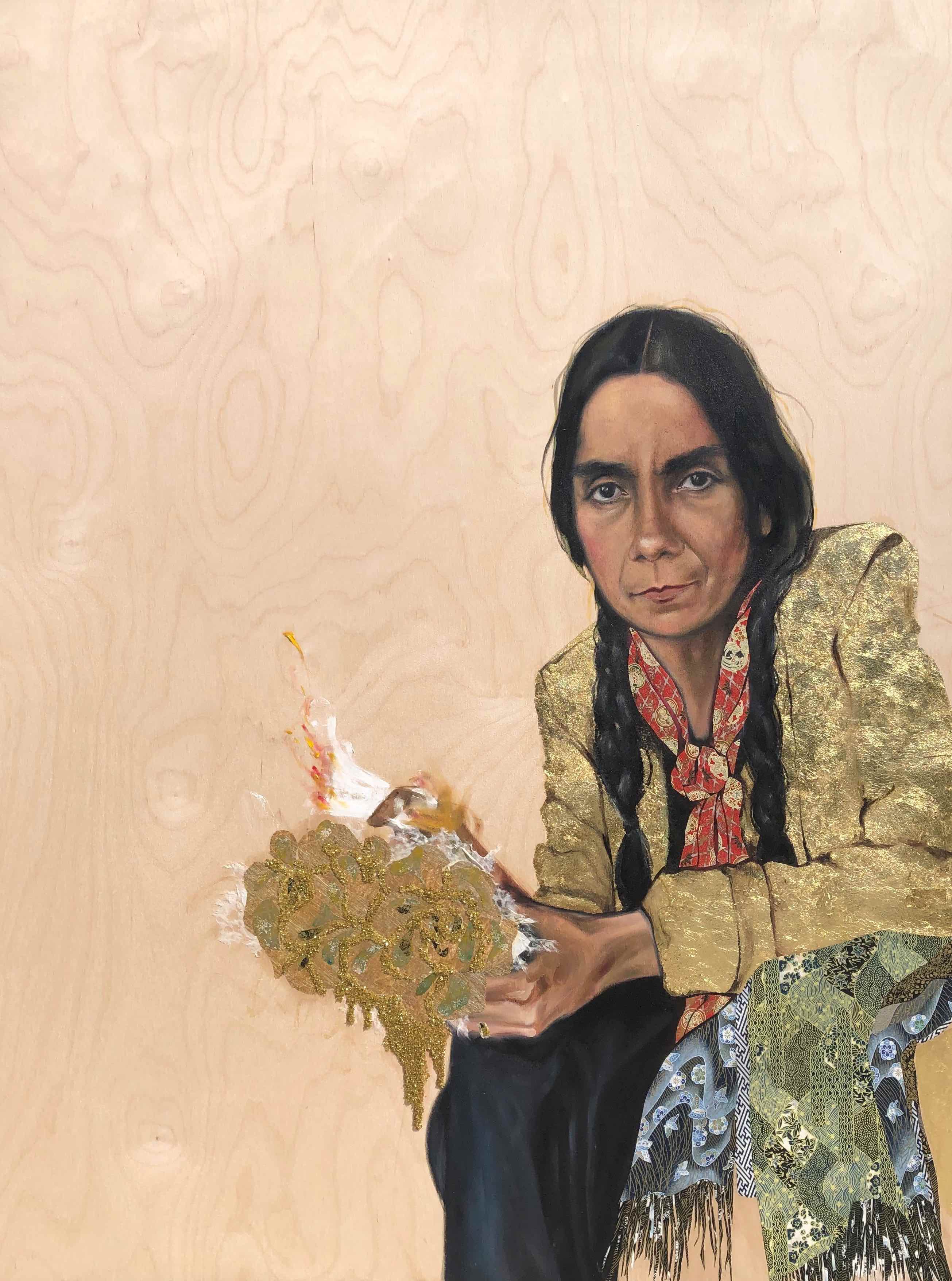

Shizu Saldamando, “Grace and Ira, Golden Hour At and Despite Steele Indian School Park,” 2019, Mixed media on wood, Courtesy of the artist

Painted portraits, historically speaking, were once a luxury afforded to those of considerable wealth and power. They were created to emphasize the importance of the sitter, and were often made to reflect the sitter’s virtues, tastes, and background. This hefty tradition, loaded with classist and racist baggage, has been reimagined by contemporary artists for decades. Not to mention that the invention of photography, despite having its own set of problems, has flattened out the hierarchy of images.

Shizu Saldamando’s portraits often begin as snapshots of friends and acquaintances around her predominantly Latinx community of East Los Angeles. With photography, Saldamando captures the likenesses of those in her circle, but through the translation from one medium to another, she is able to amplify the details with meaning. Her sitters are often marginalized as brown, queer, and punk, but Saldamando treats her subjects with dignity and validation.

Saldamando’s exhibition at the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art features recent painting, drawing, and video work. Intermingled throughout the exhibition are images of relatives, close friends, and other artists and musicians from the scene in East L.A. In depicting the community around her, Saldamando effectively renders her own identity as a Japanese and Mexican American visible. The portraits not only reveal details pertaining to each subject but also collectively constitute a portrait of the artist herself.

The context of punk music reverberates throughout the show. Saldamando’s subjects are depicted at shows and sport band tees and back patches. A set of three drawings focuses on the heavily stickered lunch boxes of Saldamando’s friends. One portrait features the hairy-chested Martin Sorrendeguy (of queer hardcore punk band Limp Wrist) donning a blue tutu that transforms into swirling waves. These images are of people with the agency to be seen the way they want to be seen.

Waves are also prominent as an element of sound in Ouroboros, Revolutionary Cycles or Dancing in a Circle, a video projected at the back of the gallery. Recorded at a show at Self-Help Graphics and Art, a community center in East L.A., the looped video shows a group of people moving around in the mosh pit. The scene becomes tranquil and meditative, emphasizing that although punk can be fast and hard, there’s an underlying sense of camaraderie to consider. This music is their way of moving through the world.

“I think music is such a huge part of the work in that it’s such a huge part of youth subculture in general. It’s kind of like the glue where people can find other like-minded people,” explains Saldamando. “People can come together and sort of release at a music show, and that’s an accessible therapy for a lot of people. It’s a way to escape and survive.”

Saldamando’s approach to her subjects is one of intimacy rather than objectification. She documents the folks she surrounds herself with and often looks up to. “The person that I’m drawing is usually the person that I wish likes the piece the most,” says Saldamando. This is reflected in the delicate realism of Saldamando’s portraits. Whether painted or drawn, Saldamando treats her subjects with honor.

While Saldamando makes use of artistic means steeped in tradition, such as oil paint and graphite, she also employs alternative gestures that undermine painting’s fraught history. Materials like spray paint and glitter, often more associated with street art and craft, appear throughout her work. Roughly half of the exhibition is works on paper – the rest are composed on raw wood panels.

As a material, wood is characterized by its availability and carries working-class connotations. Its untreated surface is subject to change over time, and its grain patterns function as a ready-made ground for the picture plane. For Saldamando, wood also refers to her grandfather, who made driftwood sculptures during his time spent in a Japanese internment camp.

The largest painting in the show, Grace and Ira, Golden Hour At and Despite Steele Indian School Park, in many ways serves as a key for understanding the rest of the work. Accompanying the painting is a quote from Grace, the Indigenous mother depicted in the portrait, that addresses motherhood and survival in the face of “racism, trauma, capitalism, violence, depression, and hatred.” Saldamando’s portraits aren’t solely to be seen as documentation of those who are suffering, but of those who are surviving and thriving in spite of these conditions.

southwestNET Shizu Saldamando

Through October 13

Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art