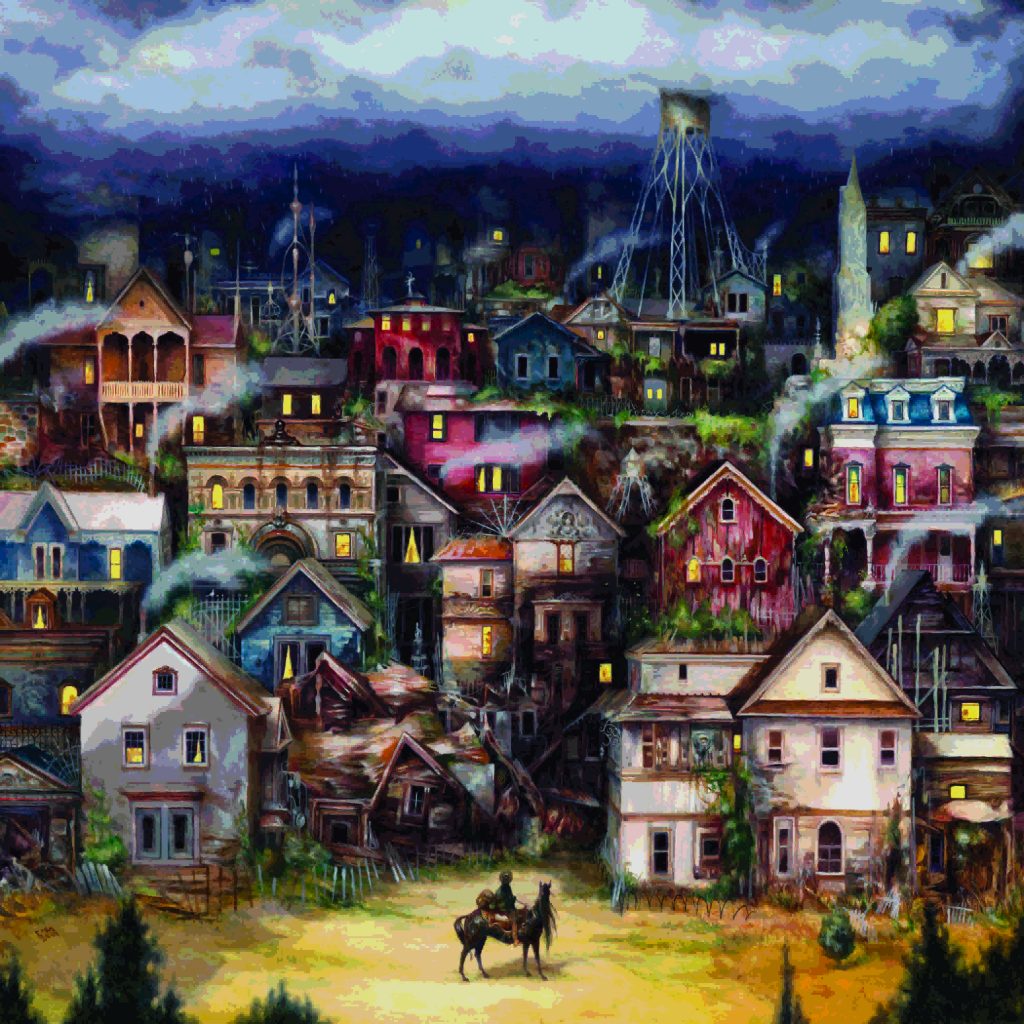

Esao Andrews’ mid-career retrospective at Mesa Contemporary Art Museum, Petrichor, evokes a lot of feelings and questions about the artist’s process and connections developed throughout his life. Viewers can easily find themselves trapped in one of the paintings, such as “Mortal Coil,”for ages – finding new characters and meanings missed at first glance.

Shifting over to a wall full of skateboard decks will have viewers looking for different things. Detailed paintings are rendered equal alongside cartoony pinups and printed photos with minimal graphic design elements, and viewers may spend less time absorbing a piece’s complexity and more time connecting each pro skater with the presented deck designs. A miniature swimming pool skull mural, journalistic sketchbook pages, and painted skateboard wheels – there is a lot to take in within Petrichor.

Though this show is considered a mid-career retrospective, there is also a lot of Andrews’ work you won’t find in the show, like his many comic book covers or web-animated pieces. For this show, he focuses on his oil paintings and skateboard deck designs, two of his stronger ties to home.

Hints of Andrews’ childhood in Arizonarun through the gallery. Growing up in east Mesa on a county island, Andrews had to walk down dirt roads with his skateboard to reach some pavement. His dad, who had been in the Air Force, moved his family near the now-closed Williams Air Force Base and became a first grade teacher for the Gila River Indian Community.

Hints of Andrews’ childhood in Arizonarun through the gallery. Growing up in east Mesa on a county island, Andrews had to walk down dirt roads with his skateboard to reach some pavement. His dad, who had been in the Air Force, moved his family near the now-closed Williams Air Force Base and became a first grade teacher for the Gila River Indian Community.

Andrews spent his youngest years combing through his family’s backyard shed full of craft supplies and a room full of kids’ activity and learning books, all left over from his father’s classes. From that point on, he has spent next to no time thinking about a future without art.

His pathway to becoming an accomplished art professional was not a smooth one – it was more reminiscent of the bumpy dirt roads of his childhood. “It was very raw desert,” Andrews recalls. Though worse now in spots than it had been, the rough environment seemed normal to him. “Growing up, it was just your typical desert. Practically every adult is riding a bicycle because they got a DUI.”

He compares his mother’s neighborhood, even today, to scenes in “Breaking Bad,” with frightening similarities. “The house across the street has car hoods for the roof, and shopping carts tied together to keep the dogs in. It was like a meth lab – and it exploded. On the front of my mom’s house, all the windows broke. My mom couldn’t have a porch light because they would steal the lightbulb.”

Andrews’ mother, an immigrant from Okinawa, Japan, worked odd jobs, as many migrants do, and shielded Andrews and his siblings from their heritage. For all intents and purposes, Andrews grew up white. He found his place within the Valley’s white-dominated skater community. He felt little to no permission to make art about the side of his identity that he “lost.”

“Being half was a very weird identity thing growing up. There weren’t any, like, real Asians out there. So my identity, the way I looked [stood out] until I moved to New York,” Andrews says. “My mom’s Japanese, so that’s my makeup, but I feel pretty foreign to it. It does [bother me]. That’s probably why I don’t do any kind of thing that seems like it’s Japanese-based. I think I’d be a fraud or something. But at the same time, I’m doing the same thing: I’m still pulling from all sorts of different cultures. I feel ambiguous.”

Andrews read JAVA as a teenager, “when it was bigger – I mean bigger in size,” and enjoyed learning about the artist community in and around Tempe and Phoenix. He reminisces about looking through the photos of people attending events and shows in the back pages, exploring the subcultures between the pages, and, in the late’90s, reading an issue whose cover featured his friend Bevin McNamara.

Andrews spent his days away from painting connecting with friends spider-webbed throughout the metro Phoenix area, converging at Fiesta Mall. Later, at the coffee-art-house Java Road in Tempe, they would skate in the parking lot or drive to a different spot. Andrews favored the Wedge the most, well before it became the Wedge it is today.

His friends in that community also connected him to some of his first jobs in the arts sector. He designed his first skateboard deck in high school, for local skate shop Turtle and Balance. Erik Ellington, who spent his teen years in Tempe, had Andrews design his first pro model on Zero Skateboards. Ellington then hired him in the years following high school and through college to design a heavy amount of decks for his own skateboard companies, Baker and Deathwish.

Andrews achieved his success through tremendous work throughout high school, building his portfolio. He convinced his art teacher to let him use art class to finish his homework from earlier periods so he could spend every minute after school working on oil paintings. Whereas most college prospectives are expected to have 12 to 16 pieces in their portfolio, Andrews was well past the 100 mark upon graduation. His future was spurred on by a recruiter’s visit to his school early on, with whom he stayed in touch. This led to a scholarship at the School of Visual Arts in New York.

Andrews had never visited New York or the East Coast before, and the culture shock turned into a benefit. The community of artists he spent time with in college was a dramatic turn from the skaters in Arizona. Though he holds deep connections with Ellington and others from his childhood to this day, the artists he met in New York pushed him to a level of competitive motivation that hasn’t been matched anywhere else. Contemporaries and fellow classmates, like James Jean, served as influencers who pushed Andrews to refine and hone his process.

“There was a renaissance going on at my school. There were a lot of really, really good students, and it was like steel sharpening steel. We were all really competitive against each other, but we were all friends.”

While pursuing his BFA, Andrews also extended his professional portfolio with illustration jobs. Though still designing skateboard decks, Andrews also picked up computer illustration jobs towards the beginning of the digital wave, mastering Adobe Flash to animate stories and characters on educational websites for kids.

His online portfolio reflected these skills. “My website would check the time of day of where you were at and change based on your time. If you went there at nighttime you’d have to use a flashlight to navigate. There were landscapes and interiors that would lead to secret rooms,” mixed in with his actual work. “Easter eggs” were littered throughout his page much like in his recent paintings.

Andrews made his mark in several commercial realms, but often at the cost of following a direction that wasn’t his own. He struggled with compromising in order to maintain a separate career of artistic freedom. But while he prefers to execute his own ideas and work for himself, his fine art and commercial illustration both strive for approval from others. Andrews believes much of his drive in both freelance illustration and personal art-making stems from a deep-rooted wish to please his parents and family.

“I’m doing it for an audience,” he confirms. “I want people to have some kind of reaction to what I’m doing and feel something.”

Andrews was glad to have the opportunity for a homecoming exhibition, and dedicated this chapter of work on display to his desert upbringing. While carrying many connotations, Petrichorsuggests the smell of rain, which reminds him of the desert.

Andrews’ older work frequently featured oceans, deciduous vegetation, and structures representative of the East Coast, often Victorian in style, illustrating his break with Arizona and pining for the unfamiliar. He describes his newer work as “Southwestern escapism,” and he spends more time exploring motifs that remind him of where he grew up. The desert has become romanticized again, and his longing manifests in pigment and narratives.

Elements of Andrews’ work always bring him back home, to heavy metal music and the horror movies his mom would watch. Meanwhile, other elements are prompted from his contemporaries, influences, and his everyday environment. Images and feelings are collaged together and presented to viewers as an open-ended puzzle.

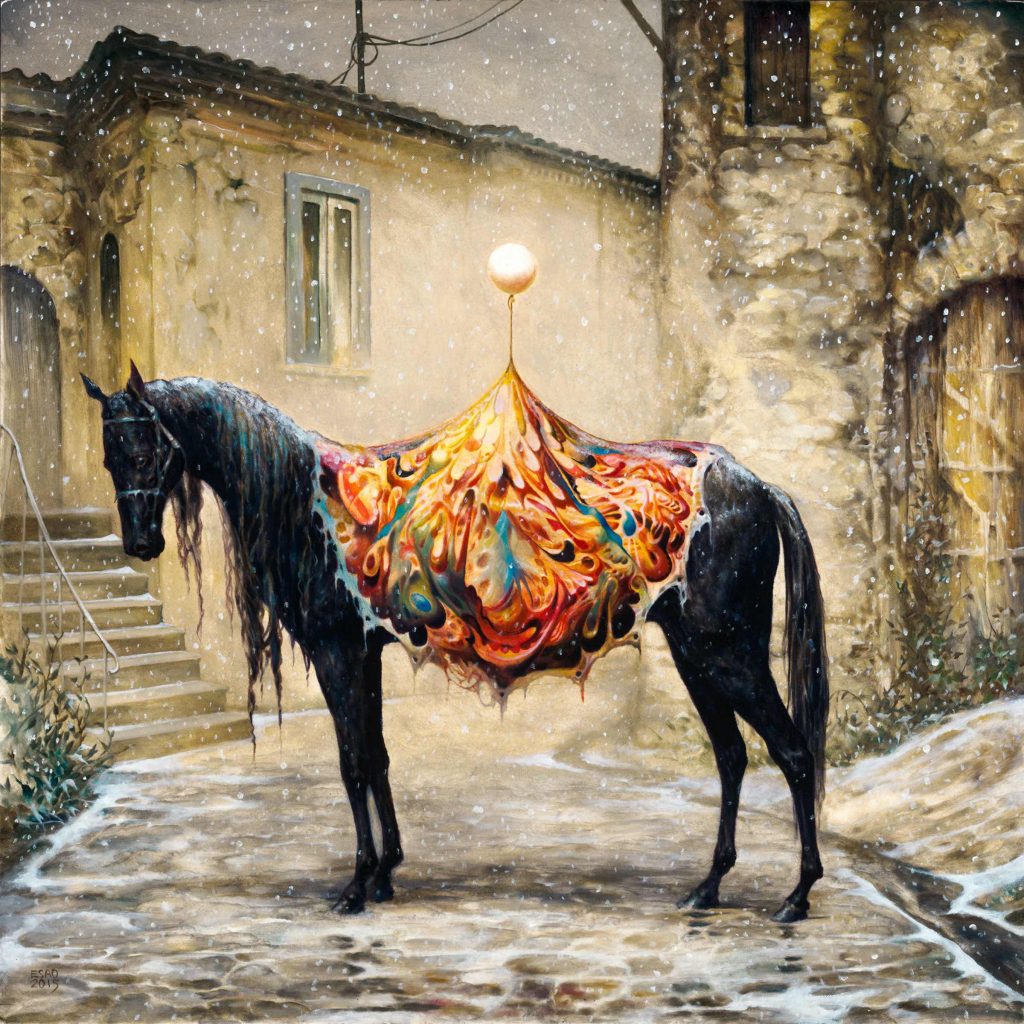

Andrews is more interested in letting others discover meaning from his work than deciding it for them. Whether it is a firefighter extending a hand through dense smoke or a man eating a Big Mac, Andrews seems equipped to combine visuals and familiar archetypes and turn them into chimeras of questions. (Those who want only a single meaning from Andrews’ work can visit his Instagram account, @esao, where he designs rebus puzzles that are notopen-ended.)

That is not to say he doesn’t spend a fair amount of his time creating work outside of ambiguity. An example of work with a specific concept in mind is a small but powerful piece presented in a display case in Petrichortitled “The Waiting Game.” In the piece, exposed remains of a genie rest inside a bottle. Andrews discloses his inclination toward scientific reasoning when exploring the realities behind fantasy, while dissecting a common storyline to reveal the fate of a supernatural deity whose dependence on a mortal being proves fatal.

“What if nobody came? How long does magic last? From a scientific point of view, what if so much time passed – we’re not talking thousands of years, but if millionsof years passed – if the sun turned into a super-giant, and if Earth just didn’t exist anymore, it was just a rock, dead of life – is he still waiting? Is he waiting for eternity? What if he waits so long that the magic is gone?” He quiets, and then reasserts his point. “It’s beautiful, tragic, and very real.”

Romantic abandonment, which Andrews draws as a storyline of “The Waiting Game,” is found throughout Petrichor, in his brushwork and his eye for detail in storytelling that provokes a second, third, or sixth look at the work. The moods within the show, coupled with Andrews’ Poisonous Birdsbook release on the night of the opening, mix sentiments of coming home with saying goodbye and letting go.

After wrapping up a major chapter, Andrews looks forward to taking people from the gallery and bringing them into his surreal narratives within a real-world setting. He is preparing to take on larger projects, both three-dimensional and functional, and enter the realm of public spaces. He aims to manifest his storytelling in public art projects and is readying himself to dive back into computer-rendered art, for 3D modeling this time around.

Perhaps it is the idea of a greater impact that motivates him in this direction, or reminiscing about systems in which people choose to lose themselves. Or maybe it’s his desire to break beyond a canvas, a phone screen, or an inauthentic reaction, to form deeper and more sincere connections with people.

Petrichor

Through August 4

Mesa Contemporary Art Museum