A common perception of the ’60s to ’70s is that everyone involved in social change embraced communal, “free love” ideologies—hippie collectives with visions of utopia as a pooling of resources, reliance on peers and lots of groupthink.

But not all of the tastemakers of that era embraced these attitudes. “Repositioning Soleri: The City Is Nature,” an exhibit opening at Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, embraces the more artistic side of this well-known, visionary Italian architect.

Taking the easy road, “tuning out” and unplugging was never part of Soleri’s vision, explains SMoCA contemporary art curator Claire C. Carter. “He was very suspect about institutionally enforced rules and order,” Carter says. “He didn’t want any religious or political overtones for his community.”

The artist-architect, after all, came of age at university in Italy under fascism. When he relocated to the United States, he embraced the American spirit of freedom and liberty, but he never was one to loaf. Soleri embraced hard work and individualism, Carter explains. This is evinced by his strict personal daily regimen and the hard manual labor he introduced to students and apprentices working at the Cosanti foundry and doing construction at Arcosanti.

The “Arc-ology” plan for futuristic cities was based on ideals of efficiency, sustainability and walkability, along with an appreciation of the arts. Soleri did celebrate the sense of community, Carter says, but he still believed in a balance of individual thought and work. His plans for Arcosanti—the idea to build up instead of out—were very much a response to the materialism and urban sprawl that sprung from the 1950s.

Carter began research on Soleri in 2010, and by 2013 she knew there would have to be a much more well-rounded retrospective than any that had been mounted before. The book she produced to accompany the show and corresponding catalog, Repositioning Paolo Soleri: The City Is Nature, represents seven years of her research.

The more Carter got into his timeline, the more she came to realize that 1969-1970 was a very important year, marking the height of Soleri’s prolificness. In that year, he had a well-referenced debut at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington D.C. His work then traveled to the Whitney, then to Chicago, then Canada, and finally landed at Berkeley.

But the last time he had a really large career show, it included only a small catalog. This motivated Carter to produce something more comprehensive—an overview of a lifetime of work, art and plans. “Soleri was really controlling about what was published on him. He always had a hand in the writing, editing and crafting,” Carter says. She believes SMoCA’s catalog is the first impartial piece of writing on Soleri produced outside of his own foundation.

Many of the items on view are very delicate, having survived decades of often not being kept in museum-style archival storage. “The exhibition is filled with a lot of ephemera that has never been displayed before,” Carter says.

Some of these items of interest include giant scrolls. Soleri liked to create city plans on rolls of butcher paper, unrolling as he went. He usually worked on a drafting table that was only 12 feet long. He’d keep drawing as he unrolled the paper. One of the scrolls to be placed on view is a large drawing of Macrosanti, the second major city design Soleri imagined for a high-density community. When unrolled, the scroll is 528 inches long—44 feet, Carter says.

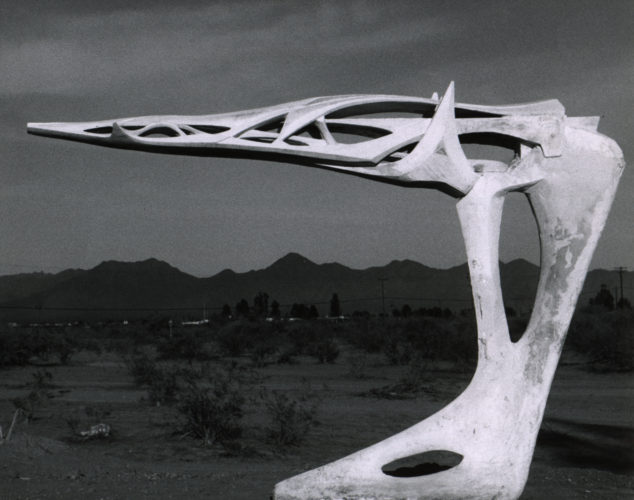

Another part of the exhibit that will captivate visitors is a collection of bridge models, thought to have been lost since 1971. “I was interviewing all these people about where these models might be, and everyone landed on the conclusion that they were thrown out,” Carter says.

They had never made it home to Cosanti after a traveling show whose final stop was Phoenix Art Museum—so it was assumed. But Carter and friends searched high and wide across Cosanti and finally found the bridge models in a storage room that hadn’t been excavated in 40 years. Luckily, they were safely packed in crates, with nothing piled on top, only around, hiding them from view.

SMoCA pledged to the Cosanti Foundation and to private collectors that it would return anything it borrowed in better condition than originally found. The museum paid for a lot of conservation, and if they mounted anything, they used archival materials, Carter explains. “It’s recent history in a lot of ways, but sometimes recent history is the easiest to lose track of,” she says.

In 2013, shortly following Soleri’s death at age 93, SMoCA hosted a museum show honoring his memory, Paolo Soleri: Mesa City to Arcosanti. Mesa City was Soleri’s first big vision for a whole city plan. That show focused on Soleri as an architect, but this one, Carter says, focuses on Soleri as an artist.

Repositioning Paolo Soleri: The City Is Nature

October 14, 2017 through January 28, 2018

Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art

For more information, visit smoca.org

Images:

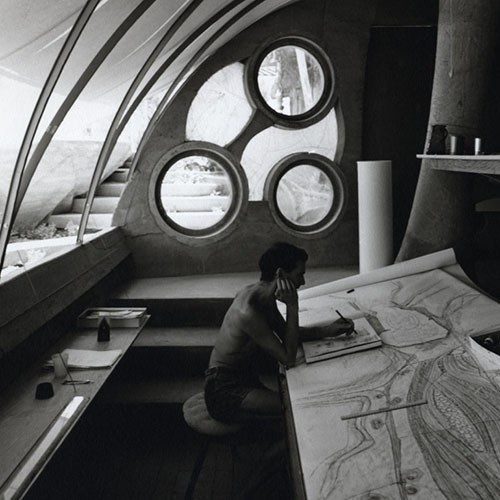

Stuart A. Weiner, [Soleri sketching at his desk, Cosanti], ca. 1960. Gelatin-silver print, 10 x 8 inches. Collection of the Cosanti Foundation. © The Weiner Estate

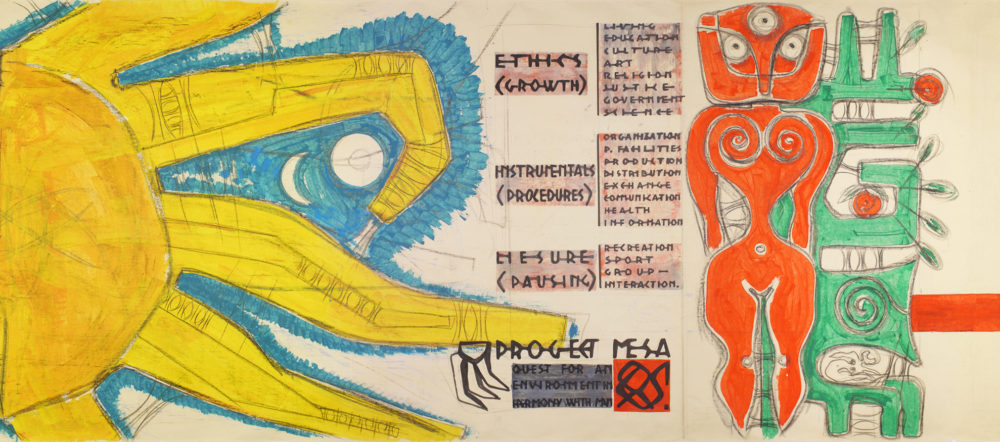

Paolo Soleri, detail, History of Man, ca. 1960. Acrylic applied with spatula, charcoal, brushed black ink, watercolor, pastel, colored wax crayon and graphite on wove paper, 704 x 36 inches. Collection of the Cosanti Foundation. © Cosanti Foundation

Paolo Soleri, Mesa City, Arts + Crafts Villages C-D, 1961. Charcoal, ink and pastel on paper, 48 x 212 inches. Collection of the Cosanti Foundation. © Cosanti Foundation

Paolo Soleri, Untitled bells, ca. 1960 – 1968. Ceramic, bronze and aluminum with copper wind sails and metal hardware, dimensions variable. Collection of Will Bruder and Louise Roman, Phoenix. © Cosanti Foundation

Paolo Soleri, Single Cantilever Bridge, early 1960s. Plaster, silt and adhesive; top element: 16 x 15 x 78 inches and base: 45 ½ x 14 ¼ x 29 inches. Collection of the Cosanti Foundation. © Cosanti Foundation