I was greeted by Jessica Palomo at her apartment/studio in central Phoenix, where she lives with her husband and two rescue dogs, Bowie and Duwee. The dogs greeted me with both caution and curiosity but quickly sensed I’ve got two of my own at home. While Duwee retired to another room, Bowie stayed during the entire interview, only interrupting once to show off a squeaky toy.

Jessica wore moon sneakers and a satin palm-tree bomber jacket. She has jet black hair, with the exception of a streak of white that changes sides depending on how she parts it. Her longish hair won’t last, though. Soon she’ll be going back to what she calls her Justin Bieber cut. It doesn’t matter what she wears, she notes, as long as the hair looks great. Jessica has a confident demeanor that’s softened by insights about art and life, speaking humbly about her work and process.

Jessica grew up in Texas among a large family. Her mother owned a hat business and her father was a history teacher. She received her BFA from Southern Methodist University in Dallas, and taught middle school and high school before moving to Phoenix to enter the MFA program at Arizona State University. There, she studied under professors Anthony Pessler, Susan Beiner, and Janice Pittsley, receiving her Master of Fine Arts degree in 2017. She’s currently a faculty associate in ASU’s art department, teaching various undergraduate drawing classes, including introduction to life drawing this semester.

Palomo has exhibited her work locally, nationally, and globally. In 2011, she was the artist in residence at the Palazzo Rinaldi program, which included a solo exhibition in Noepoli, Italy. She was the recipient of the Nathan Cummings Travel Fellowship and the Martin Wong Foundation Scholarship, among other awards. In 2018, Palomo took part in the 2018 Arizona Biennial at the Tucson Museum of Art. Last year, she showed with Cami Galofre in the two-artist exhibition Ensnarled with Flowers, I Fall on Grassat Phoenix College’s Eric Fischl Gallery. Palomo’s work is currently on exhibit in the Project Space and lobby at Bentley Gallery in downtown Phoenix. The show runs from January 17 through March 14, 2020.

In undergraduate school Palomo worked primarily in sculpture, using drawing as a way to conceptualize what would end up being three-dimensional art. Her sculptural work is derived from the organic but is finished with an artificial, glossy look that does not attempt to replicate the natural but rather plays on that disconnect. There is an intricacy to the pieces, especially in the “Weaken Defensives” series, which are constructed of pig intestines and resemble cancerous cells or marine echinoderms. She also uses materials like limestone, plaster, bronze, and wax.

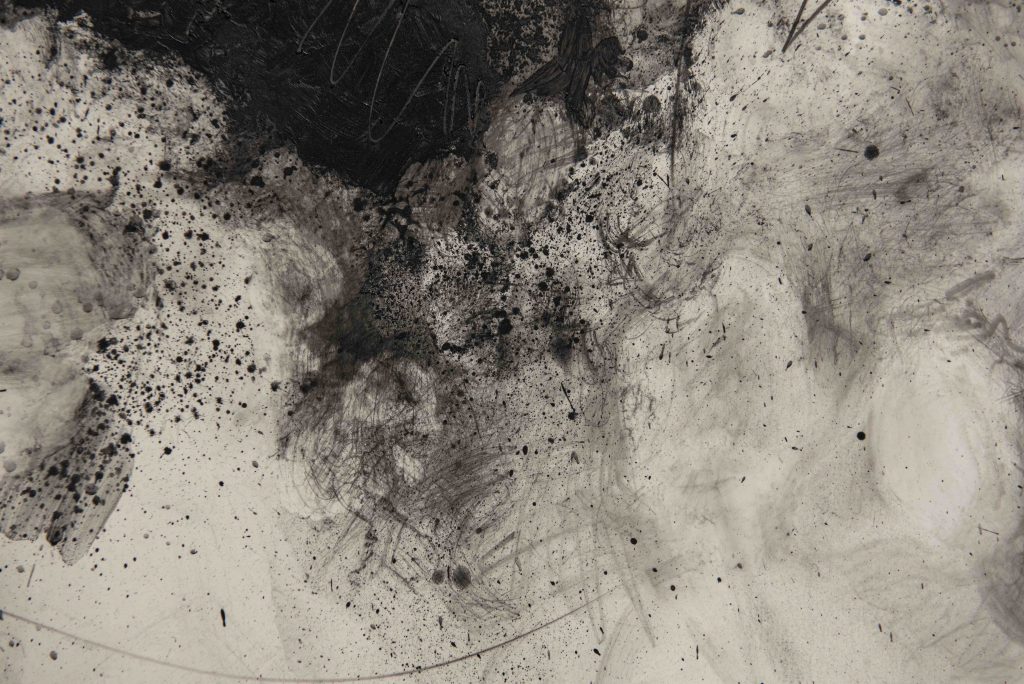

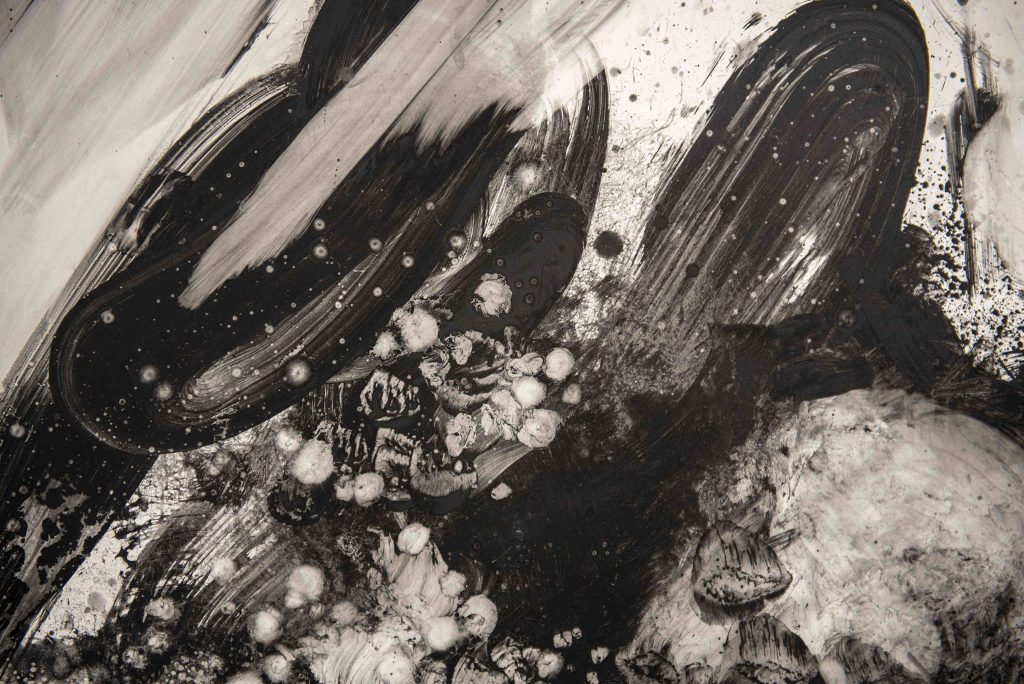

Palomo’s most recent work stays in two dimensions, however, consisting of graphite, ink, and gesso applied to boards. In ethereal black-and-white compositions she layers imagery that is sometimes familiar but at other times abstract. There are discernible shapes that may come from cell structures and muscular systems, but other shapes reference plant species. In fact, the artworks are named after plant families such as Asteraceae (often called the sunflower family) and Zantedeschia (one of which is the calla lily).

As far as process, to get the specific look of these works, Palomo uses an absorbent gesso instead of regular gesso (which looks more plastic and sits on the surface). The absorbent gesso helps make the surface more like watercolor paper, enabling her to work and rework the marks to create a sense of depth. That’s one of the things that’s striking about the images – the number of layers built with lines, washes, and brush strokes in each composition and integrated wall drawings.

What’s more, Palomo does something not many artists are able to do, and that is to dismantle a finished piece of art. Her larger mixed-media works, once completed, are cut up to create several panels. Palomo says she finds it liberating to be able to treat her art with such irreverence after putting so much emotion and time into each piece. Once separate, however, the panels may be reworked until she feels they are complete.

Individual panels may then be hung adjacent to each other in site-specific installations like at Bentley Gallery, where she connected the panels by drawing directly on the gallery’s walls. Palomo also applied this method at the 2018 Arizona Biennial and earlier in a shipping container installation on Roosevelt Row. This approach, in effect, creates another layer of depth for the viewer to engage in. And, being wall-specific, it makes each presentation of the work unique. The spacing of the work is an important component for Palomo, which she hopes leaves the connections open for interpretation.

Where does Palomo find the inspiration for her art? Much of the work stems from the experience of losing her mother to cancer. She draws on this to ask questions like: What does trauma do to us? How do we deal with extreme emotional states? Where do we place painful memories from the past? Her art also deals with feelings of being uncomfortable and not being able to put feelings into words.

But while Palomo’s works and exhibitions may appear flowery, decorative, and at times colorful (she has been steadfast in sticking to black and white only recently), there is an edge that can be overlooked. She calls her work “total experiences” and says the process is the most important part for her, as well as the “most draining.” Indeed, there is conflict, pain, and tension found in the beautifully rendered escapes. These emotions are more evident upon closer look at the marks that make up each composition.

Palomo has been influenced by artists such as Rebecca Horn, Louise Bourgeois, and Kiki Smith. She said she was obsessed with Horn’s early body-extension performances that pushed the artist to her physical limits. With Bourgeois, she was encouraged by the artist’s explorations with sculptural materials, among other aspects of the wide range of mediums she produced work in. Kiki Smith was another influencer in terms of how and when to use certain materials.

To get into ASU’s Master of Fine Arts program, Palomo submitted drawings that were process-based and dealt with her response to cancer. While not being completely aware of it, she was influenced by abstract expressionism (a movement that was mostly dominated by males, although many women painted in the style and even changed their names to fit in) and by its emotional characteristics, as well as the concept of “action painting,” but with more control over the medium. In graduate school, while searching for her unique voice, she says the most important criticism she has ever received has been, “This is nice, but anybody can do this.”

What does a Texas native have to say about Phoenix as a destination for creatives? Palomo finds a lot of support in the Phoenix art community, where she feels integrated and inspired. She has a group of close creative friends who are able to bounce ideas off each other and provide often needed motivation to keep working. That group, she says, fuels her creativity and drive.

The thought of modules of small creative groups thriving in Phoenix is an exciting one. There could be several movements happening simultaneously that may not be evident until years to come. Art can be a solitary process, and many artists have a need to stay in that space, but eventually breaking out to find response to the work created is almost critical.

A well-known patron of the arts once said to me, “It becomes art when you show it to someone else.” Well, one might argue that point, but one thing is for certain: Community, like competition, fuels the creative process. Let’s hope it continues to flourish with artists like Jessica Palomo and others here in Phoenix.