The door opens and David Emitt Adams leads me into a room full of equipment and tools stacked from floor to ceiling. The scene is frenetic with repairmen all around. We make it out of the space and I’m eventually led into a living room. There we encounter Claire A. Warden, Adams’ wife of three and a half years. She graciously offers me tea, and we chat about their lives as thriving creatives in Phoenix.

The artist couple just got back from a three-week trip to India to visit Warden’s family. They are both jet-lagged, but there’s no time to take a break. Adams is preparing to travel to Lawrence in a couple of days to teach at Kansas University for the upcoming semester.

Adams and Warden are the embodiment of working artists. They make art, for sure, but they do so much more. Both are educators: Warden runs the photo program at New School for the Arts and Academics in Tempe, and Adams has taught at several colleges. They do countless photo workshops here and abroad. Both of them have been individually awarded the Research and Development Grant from the Arizona Commission on the Arts as well as the prestigious Artists’ Grant from the Phoenix Art Museum.

Adams and Warden met while studying photography at ASU. Since then, they’ve been busy growing their art careers here in Phoenix and beyond. Nonetheless, one of their most important projects has been establishing a thriving live/work space on Grand Avenue.

A fortuitous property listing by Tom Carmody led to the couple buying a multiple-unit property on Grand. Carmody and his wife, Laurie, are known for rehabilitating properties and supporting artists in downtown Phoenix. In this instance, both aims were accomplished.

“That was always our plan for that place as soon as we thought it was possible to buy it,” Warden said. “We know what artists can afford. We keep all the apartments at a reasonable rent. Everybody living there now has had local shows, is involved in the art community. One way or another they’re all doing things.”

The couple has built on this momentum by acquiring the property next door as well; hence all the commotion and work happening there. Their goal over the next year or so is to convert the front space into studios, along with a community space that will feature a classroom. They want to make it available to their tenants and anybody from the community to come in and teach workshops in all mediums.

Warden was born in Montreal, Canada. Her father is Indian – from Mumbai – and her mother Canadian. The family moved to Phoenix for her father’s job. She had an interesting upbringing, having parents of different ethnicities, that has played an essential part in her art to this day. “My family was very encouraging of art and learning about art and studying art,” she said. “There was a lot of artistic talent in the family.”

“Actually when I was born, there was a Hindu priest at the hospital because my grandmother is Hindu. He did an astrological reading for my birthday, which was based on the date, time, and location in the world – all these factors. He gave a prediction of what my parents could expect out of me, and basically said I’m going to have a creative life.”

After graduating with a double major in photography and art history, Warden knew she had to diversify her artistic skillset and tried out different photography jobs. She shot weddings, worked for the college newspaper, and interned at Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art and the Getty Institute in Los Angeles. Eventually, her time working at an art gallery in Palm Springs solidified what she wanted to do.

“I spent an entire summer documenting and archiving a bunch of artwork in the gallery. I realized that was it. This work could keep me satisfied. I was exposed to more artwork every day, but I didn’t feel exhausted from doing photography all day, so I could go home and make more art. That probably was the turning point, but I tried everything that I could think of on a photo-related path. And I settled in on a combination of museum work and teaching – which is what I still do now.”

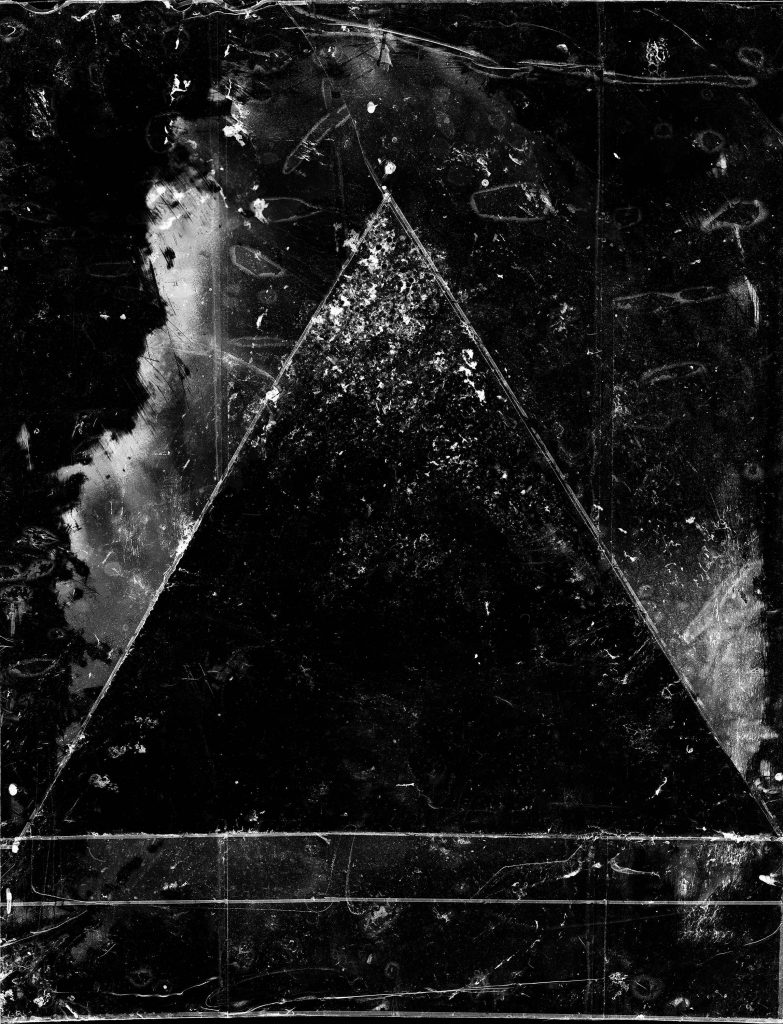

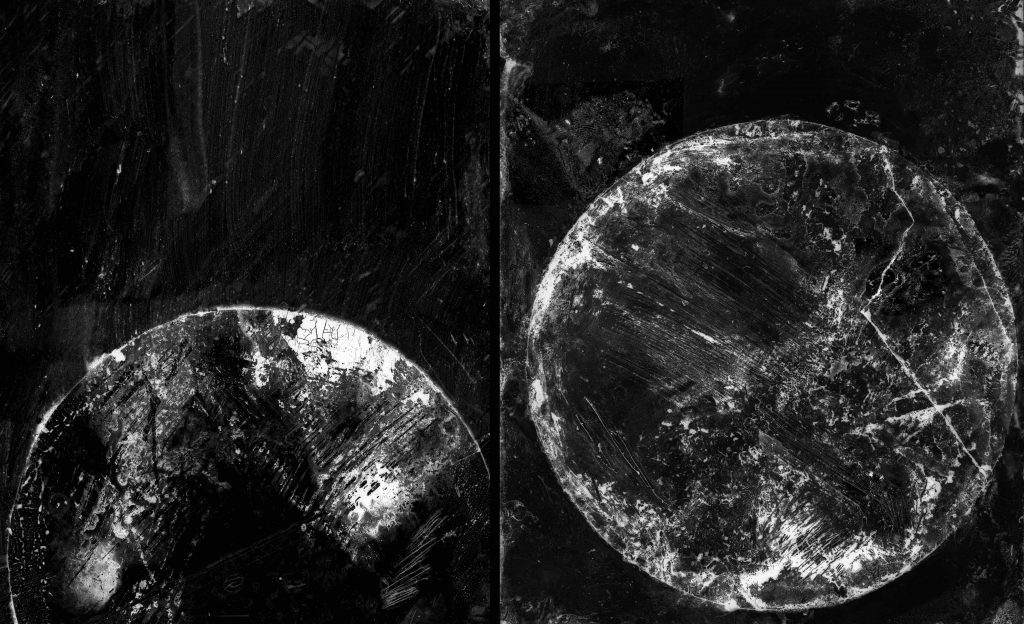

Warden’s most recent body of work, titled Mimesis, uses physical mark-making as well as applying her own saliva directly onto black and white film. The saliva affects the film in unexpected ways, resulting in images that are enigmatic but also talk about identity and what makes us who we are through the poetry of the photographic process. She has also been working on her 99Moons Project, which is “a series of camera-less silver gelatin prints made in the darkroom” that depict abstracted nightscapes.

Warden has continued to show her work at significant institutions. She recently had a solo exhibition at the Philadelphia Photo Arts Center of work selected by Lucy Gallun, curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. She also had a solo show at the Catherine Edelman Gallery in Chicago. At the moment she is featured in a group show called Qualities of Light at the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson.

Adams was originally born in Yuma, but he didn’t stay there long. His parents worked for the U.S. State Department, requiring the whole family to move every three years. They made stops in Mexico City, Buenos Aires, and Jakarta, among other places. The perpetual relocation would stop when his father retired and took over the family farm in Ohio.

Adams finally put down roots in the Midwest, but the constant travel had already made a lasting impression on him. He was compelled to capture the diverse cultures he experienced by taking photographs. This was before the advent of smartphones, so he had to make a concerted effort to do so. “I just knew I wanted to be a photographer,” Adams said. “The first camera I got was in Jakarta, Indonesia. I still have it, a Nikon F3. I was there during one of their first election processes ever. I have photographs that I made with zero knowledge of photography.”

Adams spent summers on the family farm with his grandparents. This was a huge contrast to the chaotic, bustling cities he lived in during the majority of the year. Life on the farm initiated an appreciation for those that came before him. “I think it built a strong respect for tradition, a strong respect for history inside of me as a person,” Adams said. “That’s what led to my interest in historic photo processes, but also my interest in expanding them, as well.”

Adams built his own large-format camera and darkroom in grad school. While teaching a beginning photography class, he set up a bin for his students to put their used metal film canisters in, with the intention of recycling them. He figured out a creative way to flatten them and print his students’ images on them through the wet-plate process.

“So this whole notion of photography at that point changed for me because I had always been very traditional, large format, black and white,” Adams said. “Now I can make photographs on objects that speak to the nature of what that thing is and really kind of expand my mind. This got me out of this traditional realm and pushed me into just thinking that I can do anything with photography.”

That body of work was the genesis of all his ongoing projects. Conversations with History comprises photographs that he makes on detritus found in the Sonoran Desert. Anything from old cans to car parts – Adams prints the landscapes where they were found directly on the objects. His most recent project, Power, is made up of photographs on 55-gallon oil drum lids. “I go across the country photographing the oil infrastructure and all the architecture that surrounds it, using a portable darkroom truck,” Adams said. “I drive around the country and make photographs on these objects.”

Adams is featured in Ansel Adams in Our Times, which opened at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and will be travelling to the Crystal Bridges Museum and then on to the Portland Museum of Art. Last year he was in the New Southern Photography exhibition at the Ogden Museum. He opened his first solo show of the Power series at Candela Books + Gallery in Richmond, Virginia, and currently has work at the Shelburne Museum in Vermont.

All the accolades are great, but ultimately Adams and Warden make art so they can keep doing what they love. And what they love is living the creative life of artists as a couple, which makes it all the more rewarding.

“The way that we’ve always approached our relationship, even early on when we were dating, was very supportive and encouraging,” Warden said. “If I have access to something, then David has access to it. Any grant or award that either of us gets will help the both of us, because we’re a team. It’s just our personalities that we’re constantly helping each other. Most of the time, we balance each other out.”