2018 Phoenix Art Museum Artist Grant recipients Malakai, Elliot Jamal Robbins, Papay Solomon, and Taylor James, along with the Arlene and Morton Scult Artist Award winner, Julio César Morales, insist on addressing the politics of Arizona’s intersectional and diasporic communities.

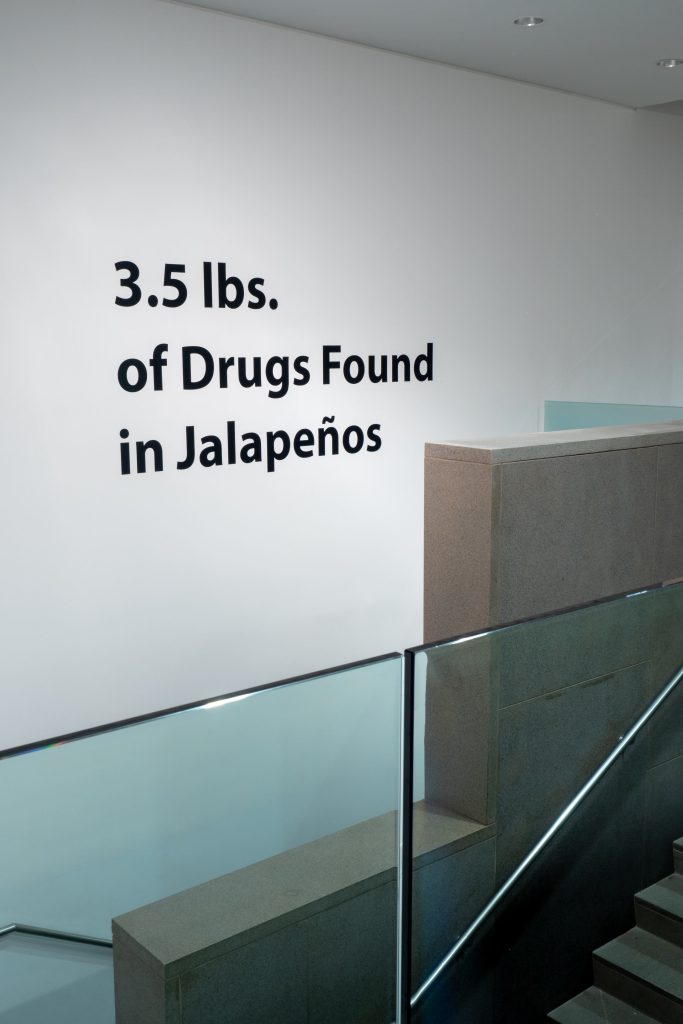

At the entrance of the exhibition glows a red neon schematic of the 1,954-mile border between Mexico and the United States, entitled “Broken Line” (Línea Rota), radiating Morales’ ongoing research and artifact production in response to the rhetoric of immigration. Two headlines reading “7 lbs. of Meth Found in Nacho Cheese” and “3.5 lbs. of Drugs Found in Jalapeños” describe in absurdist detail the methods of drug traffickers, their criminal gravity countered by the comic innocuousness of the mode of transport.

Pathos and comedy are left more unresolved in Morales’ watercolor of a man with his arms crossed, seated within the shape of a car seat used to cross the border. This image, derived from real documentary images taken by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, is part of an ongoing series that softly renders immigrant adults’ and children’s bodies folded into commercial objects, exposing the inventive yet precarious conditions of ad-hoc migration.

Morales extends the sympathetic consciousness of the liminal. In “We Are the Dead”(Somos Los Metros), the narrator inhabits the psyche (in a true account) of one of two brothers traversing the Sonoran Desert. After they separate and he survives the harrowing trek, he learns of the death of his brother: “Since my brother is gone, I no longer speak Spanish.” His loss of identification, struggle to bear witness, and evacuation of language are translated by Morales’ own poetic formalism. Installation

Julio César Morales, “Day Dreaming” 2017, Permanent pigment on Hahnemüle 350 gsm paper, courtesy of Gallery Wendi Norris

In solidarity, Taylor James photographs objects that index sites of Mexican migrant trauma: a grave marker on an isolated dirt path, skeletal remains, a black water bottle, an abandoned shoe. The images on their own can be misread as romantic panoramic landscapes or documentary object recordings, but the captions return the tragic content in deadpan melancholia: “This human atlas vertebra was found just outside the mouth of the cave. It is the first vertebra of the spinal column that connects the spine to the skull.” They are objects that function as memento more, psychologizing the supposed objectivity of photographic memory.

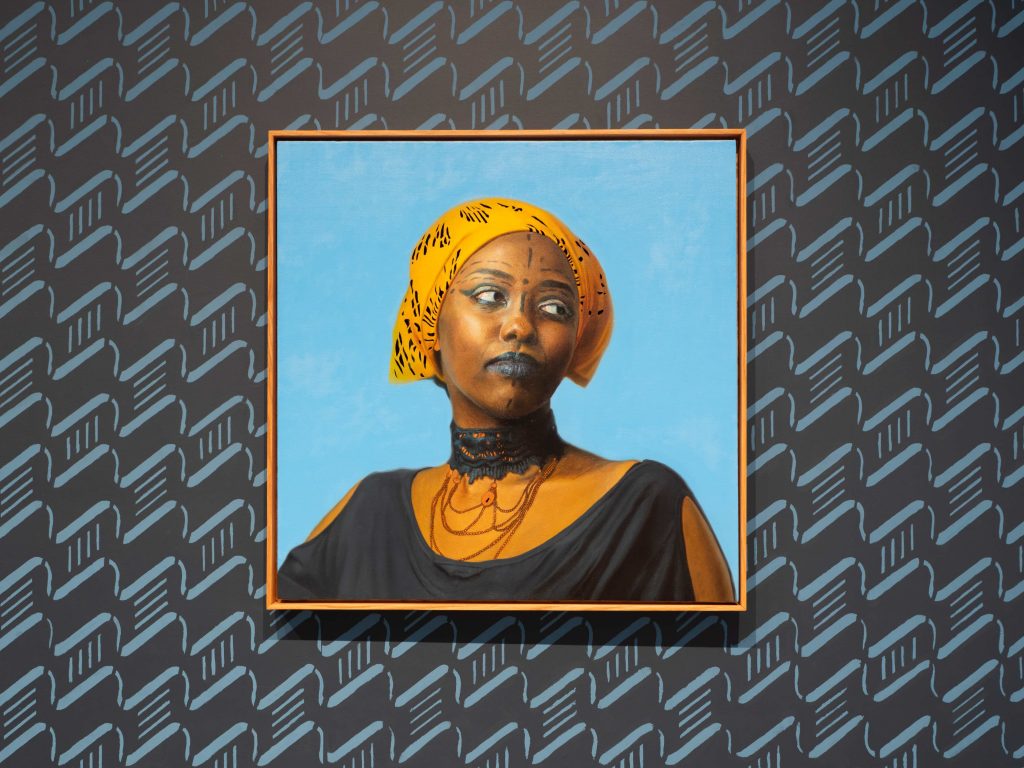

Papay Solomon’s own migratory experience as a Liberian war refugee is mediated by leaving open – or, as the artist puts it, non-finito – categories of identification. He combines Flemish painterly mimesis, figural realism, and decorative abstraction drawn from the textile and craft traditions of Liberia. His subjects are exuberant, replacing pearl earrings and silk with golden hoops, knotted headwraps, and beaded chokers. He exploits the illusionistic facility of European technique and chooses bodies and a symbolic tradition that are rightfully exclusive to his own community.

While Solomon uses classical virtuosity in the service of black excellence, Malakai’s installation involves multimedia augury. Vela Davis–designed headdresses composed of braided locks interwoven into round patterns encircle the head like a mandorla. They are artifacts of Malakai’s own future-memories presented in a three-channel film titled Souls. Set in a desert landscape, it centers on a black daughter surrounded by divinely adorned kin, situated in a heavenly realm or grounded in bedrooms of maternal intimacy. Malakai incorporates Afro-futurist design, cosmological animation, and videographic portraiture to envision a utopia from usable indigenous pasts.

Elliot Jamal Robbins’ animations recall darker hegemonic shades of utopianist fantasies. In “Nocturne (Sleeplessness/Sleep Is the Cousin of Death),” an iconic image of Snow White is superimposed with a black boy’s silhouette, scored with the ominous reportage of National Public Radio. The racialized cartoon is derived from American Colonial caricatures. Queer blackness comes into dissonant contact with Disney’s legacy of idealized feminine whiteness. The interjection of sirens brings to consciousness the aftermath of the fatalities of black men at the hands of police. The bucolic naivete of Sleeping Beauty is punctuated by Robbins’ sporadic sketching, where the figure becomes intersexed and disfigured by the crudeness of the line. At its most elegiac, the figure is blurred, hands grasping a bouquet of flowers: slumber turns into a funeral.

The Arlene and Morton Scult award stipulates that the grantee must have been a resident of Arizona for at least four consecutive years, and the Phoenix Art Museum grants require that artists be Arizona residents for two years. That is to say, the grants attempt to grow and incentivize a local art economy and build creative community. The purpose of the grant program is not only to showcase the contemporaneity of local artists and offer a counterpoint to a canonical permanent collection but also, more importantly, to make radical gestures in projecting Arizona’s political consciousness and discover who is doing the most crucial work to negotiate its discontents.

Phoenix Art Museum 2018 Artists Grant Recipients and Arlene and Morton Scult Artist Award Exhibition, installation view

Specifically, Morales’Invaders exhibition draws upon recent fear-mongering that attempts to usurp a migrant humanitarian crisis and exploit it as a national emergency. The U.S. president uses the word “invasion” to reinforce his notion of a wall in an imaginary siege by foreigners on the other side of the broken line. The combined effort of Morales, Malakai, James, Robbins, and Solomon begins the labor of empathically defining the other in terms of refugees, family, and personal identity and asserts that the penalties and risks of crossing the line are manifestly assumed by bodies of color.

“Phoenix Art Museum 2018 Artist Grants & Scult Award Exhibition”

Phoenix Art Museum

Katz Wing for Modern and Contemporary Art, Marshall Gallery, and Hendler Gallery

Through July 7, 2019

phxart.org