Phoenix Art Museum’s Contemporary Forum awarded Matt Magee the prestigious Arlene and Morton Scult Artist Award last year. The artist has spent the last year creating a new body of work to exhibit in the Marshall and Handler gallery space on the lower level of the Phoenix Art Museum.

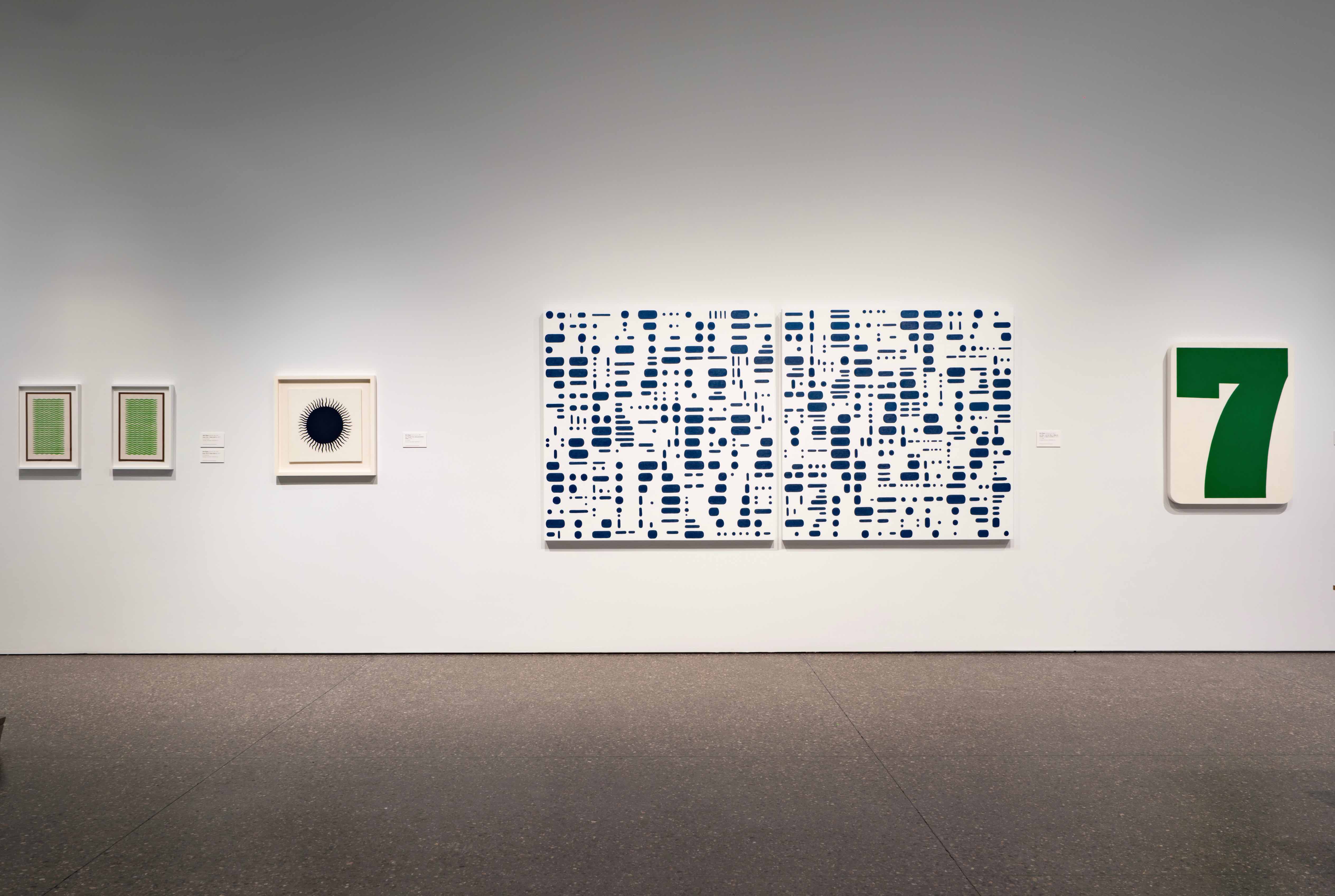

Magee takes a minimalist approach to his multidisciplinary work as a visual artist. His expansive practice includes painting, printmaking, photography and 3D sculptures made from found materials. This exhibition, showing through November 4, offers a variety of oil paintings, sculptures and found objects. The work utilizes bold color and formalism, with nods to Op Art and Hard-edge painting.

Magee has been collecting found objects for decades that speak to his curiosity, and he reimagines them to help form his visual language. Some of the materials were found over 20 years ago, such as colorful detergent bottles that Magee has cut into various shapes and strung into sculptural forms. As you walk down the staircase into the gallery, the largest sculpture, titled “Purple Rain,” cascades down the wall. The pop of color from the various hues of purple and the simplicity in form resemble a familiar mid-century aesthetic.

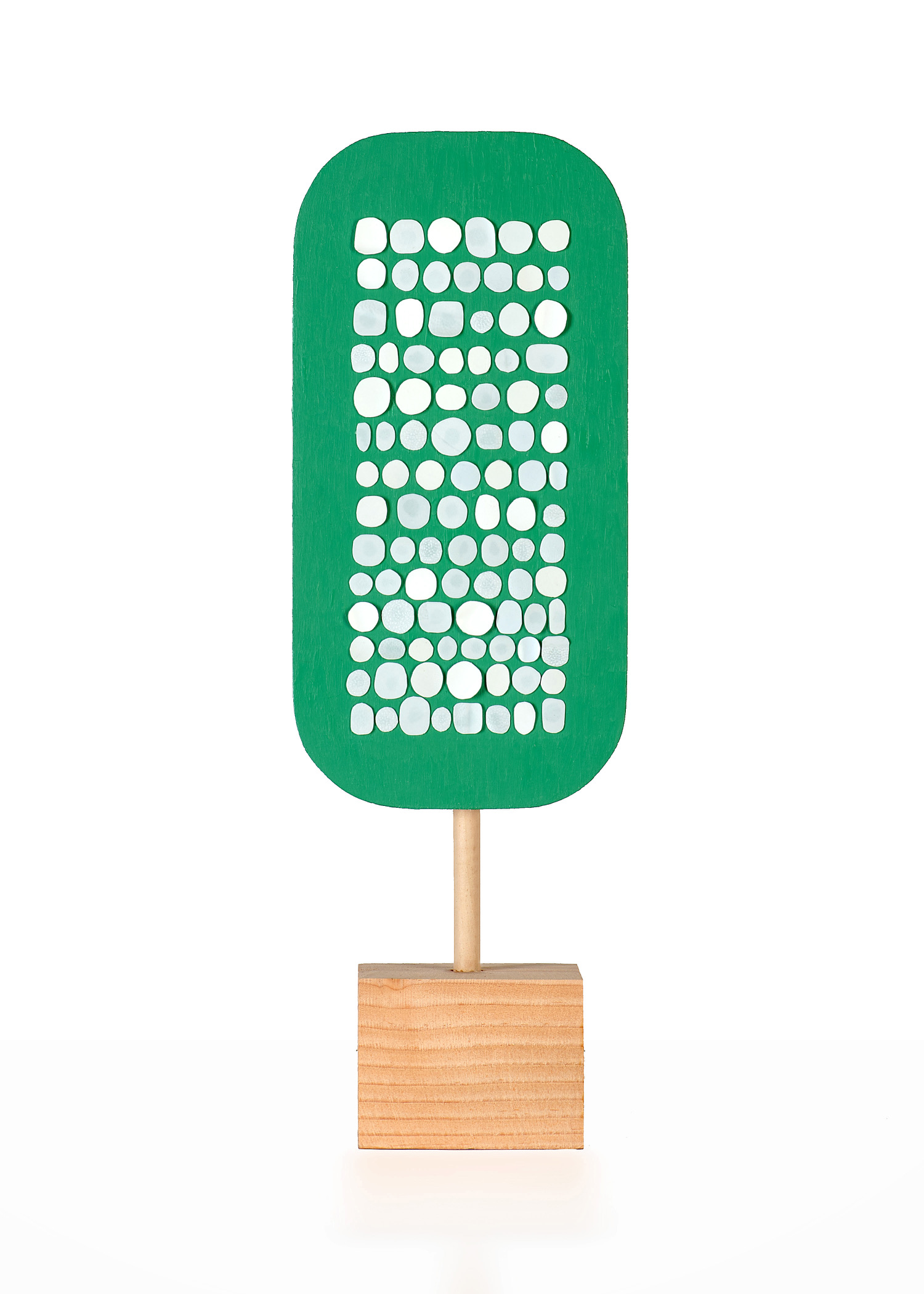

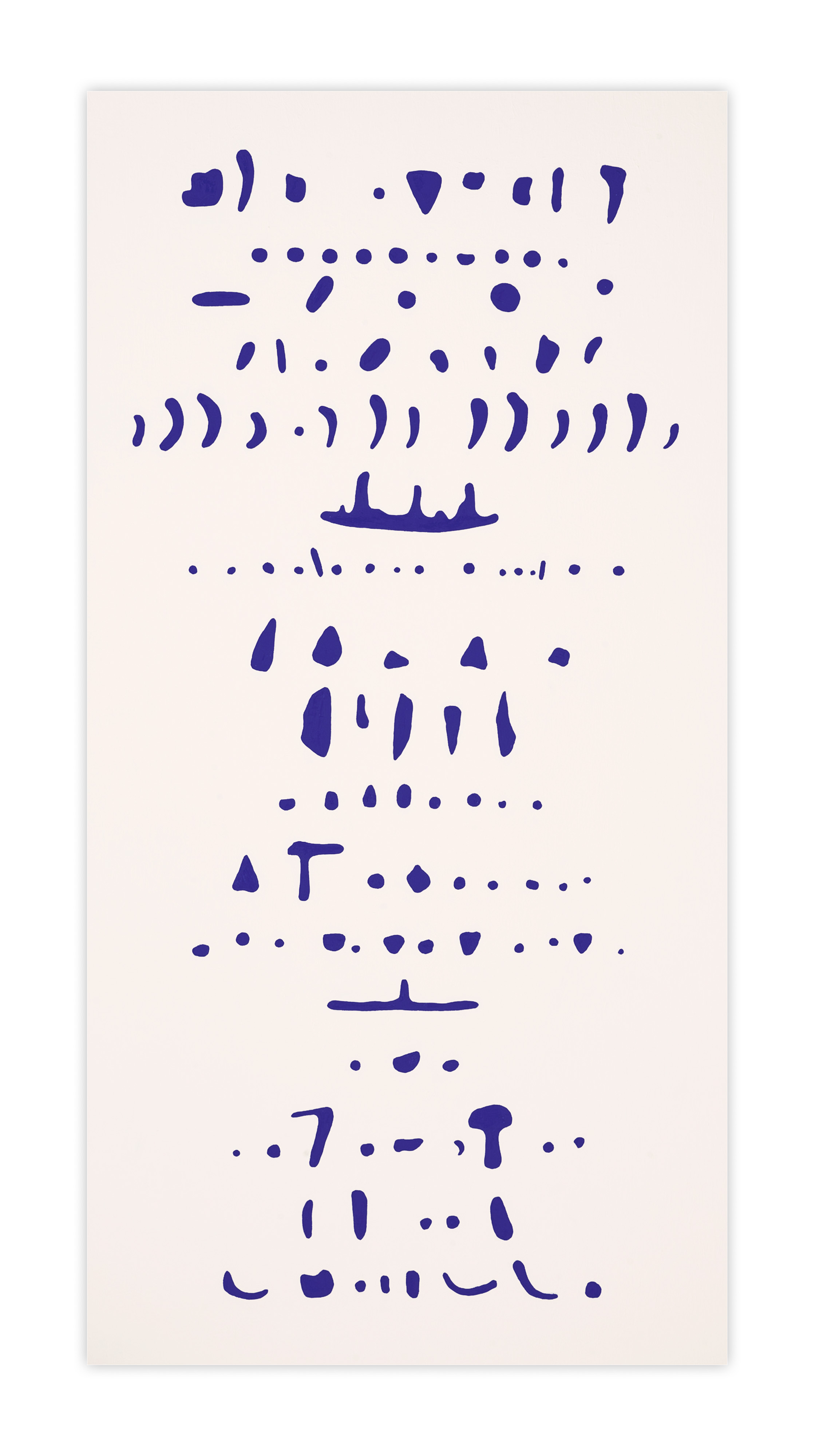

Several smaller sculptures utilize colorful repurposed plastic throughout the space, offering a vibrancy of color. Also included are several paintings that seem to use a Morse code–like symbolic language. This author’s favorite pieces are inspired by Op Art and were rendered in multiple layers of oil paint. Each piece subtly reveals the artist’s hand, up close, and allows the eyes to create movement with the line patterns from a distance.

Magee’s work as a whole comes together to explore his visual language, and yet each piece tells its own story. Reverence is shown to other artists who worked and exhibited in New York City during the ’60s, such as Agnes Martin, Bridget Riley and Sol LeWitt. Magee has always gravitated toward creative people and explored his own creativity.

He studied at Trinity University in San Antonio, focusing on art history. Magee earned his MFA from Pratt Institute in NYC, where he focused on nontraditional media and processes. During his undergraduate studies, he interned for two summers at Guggenheim Museum in New York; his last summer in school was spent interning for the Guggenheim in Venice, Italy.

Magee went on to work as an art handler and as the chief photo archivist for the seminal artist Robert Rauschenberg for over 18 years. This experience offered a wealth of opportunities and had a tremendous impact on Magee’s life and career. Magee lived in Brooklyn and worked in the five-story building on Lafayette Street in Manhattan – a 19th-century orphanage – that Rauschenberg bought back in the 1960s. Over the years, Magee has exhibited his work in New York, Albuquerque, Houston, Chicago, Connecticut, Marfa, London and, of course, Phoenix.

After 30 years of living in New York City, Matt and his partner, Randall, decided to move back to the Southwest and settled in Arizona in 2012. He currently has a studio at the Cattle Track Arts Compound in Scottsdale, which has a rich history of important artists who have worked at the historic desert ranch property over the years. Local art legends Fritz Scholder and the founder of the Phoenix Art Museum, Phillip Curtis, once lived and worked there.

Magee is currently working on a book that explores the artwork he has created over the last six years while residing here in the Valley. He enjoys working in his studio on a daily basis, and has found inspiration in the rich desert landscape and laid-back lifestyle.

JAVA recently met up with the artist for a studio visit and asked him to discuss the visual language that informs his artwork:

Matt Magee: In the late 1970s, I was working retail in a mall in Dallas. After every garment shipment, we were throwing away loads and loads of plastic garment bags, the kind you get at the dry cleaner. I started bringing them home and experimenting, twisting the bags so they could be pulled through metal cloth. I also sewed cotton twine through them (fig. 1), draped them and hung them in trees and wadded them into balls and melted them with a torch. I was exploring a found medium and taking it in as many directions as I was able.

Over the years, I’ve used rubber inner tubes, plastic bottles, aluminum cans, coral and polyester resin in my practice, among many other media. Exploring these materials has made me realize there’s a communicative property in basically everything; it just has to be tapped into.

In the mid 1980s, I began collecting cast-iron stove burners from stoves I found in dumpsters in Brooklyn. I was attracted to the strangely animate forms and wrapped them in shrink-wrap, melted that with a torch, rubbed the objects with graphite and through this ritual process made them my own. By installing them in rows they became a kind of alphabet and visual language, and I took this as a cue (fig. 2, Wrapped Alphabet, 1985-1989).

In the late 1980s and into the 1990s, I collected coral from the beaches of Vieques, an island near Puerto Rico that I visited five times. One day in 1992, I took this photo of the coral I’d found, and it was suggestive of an arcane language. Completely natural shapes that were mimetic of works by 20th-century sculptors I’d studied in undergraduate art history classes (fig. 3, Coral Key, 1992, c-print).

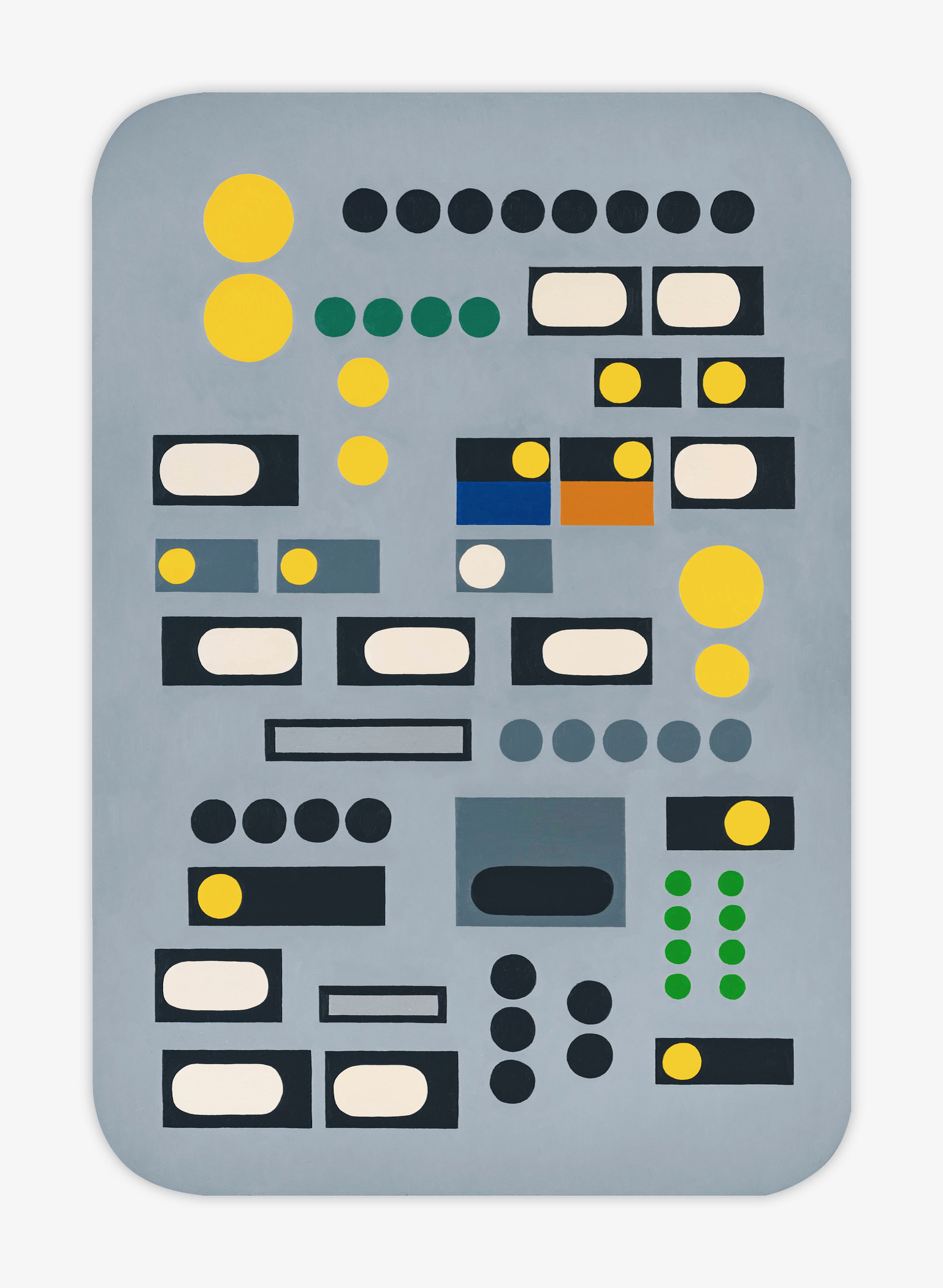

Around 1994, I began painting again and was inspired by a work that my great-great-grandfather made in 1870. Jonathan Stickney McDonald was an artist, mason and philosopher and, like many in his day, followed the Theosophy teachings of Mme. Blavatsky, a Russian-born occultist and spiritualist. His personal cosmology and specifically his spiritual painting inspired and directed my own series of symbolic paintings that, when installed, spelled out a personal language and inaugurated what I call a visual belief system, which has become the foundation of my practice (fig. 4, c. 1994, Installation at Hiram Butler Gallery, Houston, 2013).

Figure 4, Various artworks c. 1994, Installation at Hiram Butler Gallery, Houston, 2013. Image courtesy Hiram Butler Gallery

Continuing to the present day, commonplace and found object remain touchstones for my work. Receipt, a painting from 2016, directly references a blurry receipt received from a cashier. All that could be seen in the small slip was an iteration of abstract shapes in rows, which in my mind’s eye became an alchemical formula and the format for a painting on panel. The reference to an archaic intuitive language of form through tool and implement shapes emerged simply from the unfocussed ink generated by a cash register (fig. 5, Receipt, 2016, oil on panel).

And finally, a recent image taken of an installation in my studio at Cattle Track in Scottsdale. On the wall is Poem for Dublin, a 10″ x 40′ painting of a double-printed fortune that I found inside a fortune cookie one day. The randomness of the text and the idea that this could be some kind of fortune written in JavaScript was intriguing. The painting was shown at my London gallery a year or two ago and has a James Joycean wit with a sense of the Gaelic in its double-printed run.

I’ve titled this studio installation The Upanishads and Poem for Dublin. I’ve not read the Upanishads but understand them to be a collection of Sanskrit texts that form a belief system. The processes, forms and sequencing in my studio practice are the components of my own particular visual belief system (fig. 6, The Upanishads and Poem for Dublin).

The 2017 Contemporary Forum Artists’ Grant Recipients exhibition will be on display at Phoenix Art Museum through November 4. The exhibition also features the work of Christopher Jagmin, Casey Farina, Jennifer Day and Laura Spaulding Best.