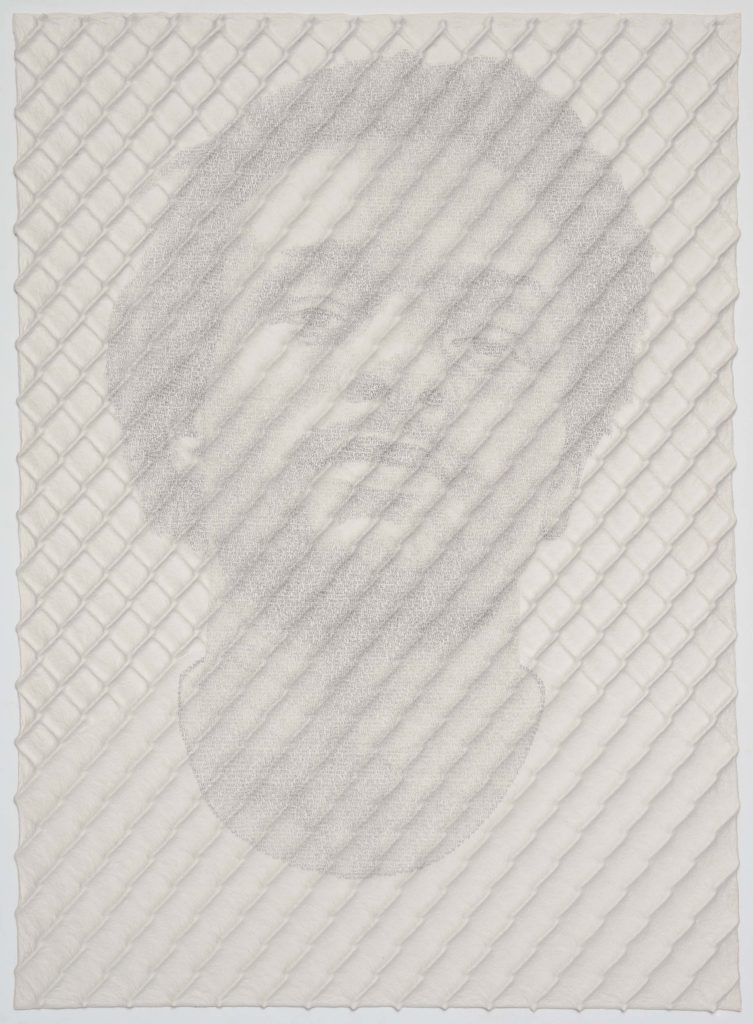

Ben Durham, “Chain-link Fence Portrait (John),” 2017, graphite text on handmade paper and steel chain-link fence, 65.25″ x 49.5” framed, Image Courtesy Lisa Sette Gallery

How many shades can the color white yield? The latest show at Lisa Sette Gallery dazzles with an expansive spectrum of media and practices framed under the title Subversive White. Aimed at the current national conversation, the works of fourteen artists in this exhibition refract the light of white supremacy and speak out against its oppressive system.

Without first reading the curatorial statement, the explicit theme might not be immediately apparent. The exhibit aims to show as many pieces, with as few similarities of scale, material, or formalism, as possible. Taken individually, the works demand undivided attention. Some works are coy, others damning. Some complete the aesthetic pun of white on white, like Sonya Clark’s “Whitewashed”(2017):an American flag that cannot immediately be discerned, as it’s painted in shades of white. As soon as your eyes adjust, your entire field of vision is filled with subtle hues like “Incredible White” and “Natural Choice.”

Many of the works deal with the legacy of white supremacy by showing excerpts from America’s history. Fiona Pardington’s “Phrenology Head” (2018) and Rob Kinmonth’s “George Washington’s Dentures, Mount Vernon, Virginia”(2016) are photographs of haunting objects.

These works draw upon common history but also ground the exhibition in a common specificity.

Mark Mitchell, “Fragility,” 2019, reed, cotton, wool, silk, wood, 7.75″ x 11″ x 9”, Image Courtesy Lisa Sette Gallery

At once tender and austere, Mark Mitchell’s “Cracker”series demonstrates that history is an act of retelling the past in the present. His sets of dynamite sticks, dressed up in debutante’s silk, are an homage to less-than-documented queer histories. These works show us (but don’t tell us) strategies for relating to the past while moving toward survival: disjunctive signals concealed in plain sight. The delicate silk and ostrich feathers are about seduction, while the dynamite promises an explosive confrontation, but the artist’s skill in sewing them together demonstrates that surviving both is possible.

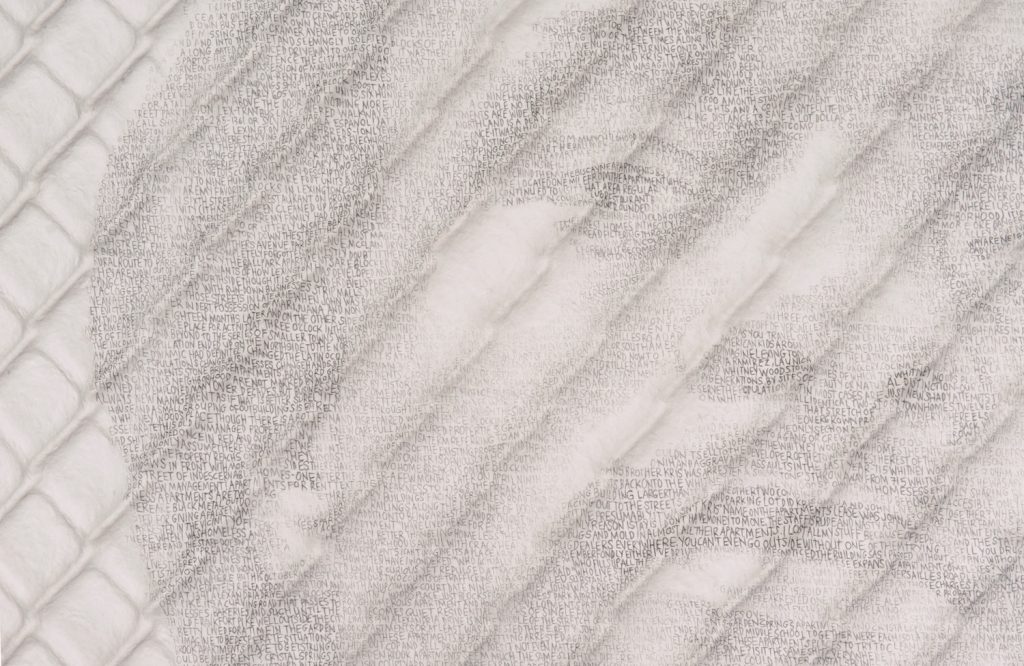

Some of the most compelling works are those that point our attention forward, either toward an emancipatory future or an expanded political imagination. Ben Durham’s “Chain-link Fence Portrait (John)” (2018) demands compassion on an industrial scale. The 65-inch-high portrait of the artist’s childhood friend is painstakingly drawn in fine lines of text across paper embossed by a chain-link fence. The texts are words of reportage, barely readable, lifted from John’s arrest record. John – or what remains of our understanding of him – fades in and out between the weight of Durham’s pencil and the language of incarceration.

Ben Durham, “Chain-link Fence Portrait (John) [detail],” 2017, graphite text on handmade paper and steel chain-link fence, 65.25″ x 49.5” framed, Image Courtesy Lisa Sette Gallery

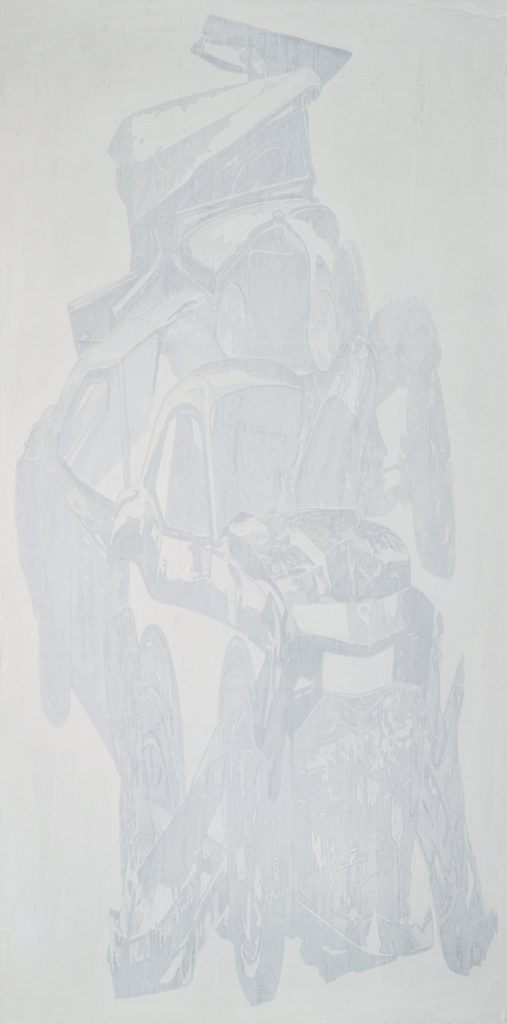

Claudio Dicochea “081217,” 2018, acrylic, graphite, charcoal, transfer on wood, 48″ x 24″ x 2” Image Courtesy Lisa Sette Gallery

The works in Subversive White find many angles for thoughtful provocation. But, in the moment after your third or fourth walk through the gallery, you’re left wondering what to do with the show as a whole. The hyper-saturation of media and images is part of the current political landscape, while the possibility of engaging and changing America’s national story is diffused in the same breath – perhaps because of the nation’s history with provocative images. John Berger writes about the stark photos published from the Vietnam War, which left readers morally wracked and politically nullified: “The picture becomes evidence of a general human condition. It accuses nobody and everybody.” What was true then may be even more so now – at a moment when American politics is television/media.

In the history of objects and images, those that address political realities are set apart because they are meant to create action. The works in Subversive White provide a captivating array of histories and responses to white supremacy. They prove that subversion is the work of an aesthetic strategy. These artists are relentless in their investigation of whiteness as a political reality and help open up new imaginative possibilities. Whatever political project this exhibition points toward, however opaque or transparent, is left up to the viewer.

Subversive White

Through April 27

Lisa Sette Gallery

210 East Catalina Drive, Phoenix

lisasettegallery.com