With Bone Thugs-n-Harmony’s “Thuggish Ruggish Bone” playing through a massive sound system, a lowrider truck with Daytons shining onto the asphalt cruises along the streets of Phoenix, a six-year-old girl and her father aboard.

This memory, and others like it, drove Antoinette Cauley through kindergarten, eight different elementary schools, and familial hardships, and into a blazing artistic career that has blossomed like a cherry bomb. These types of memories and music feed into her work, which is optimally viewed with Nipsey Hussle’s “Overtime” (among other tracks) playing in the background.

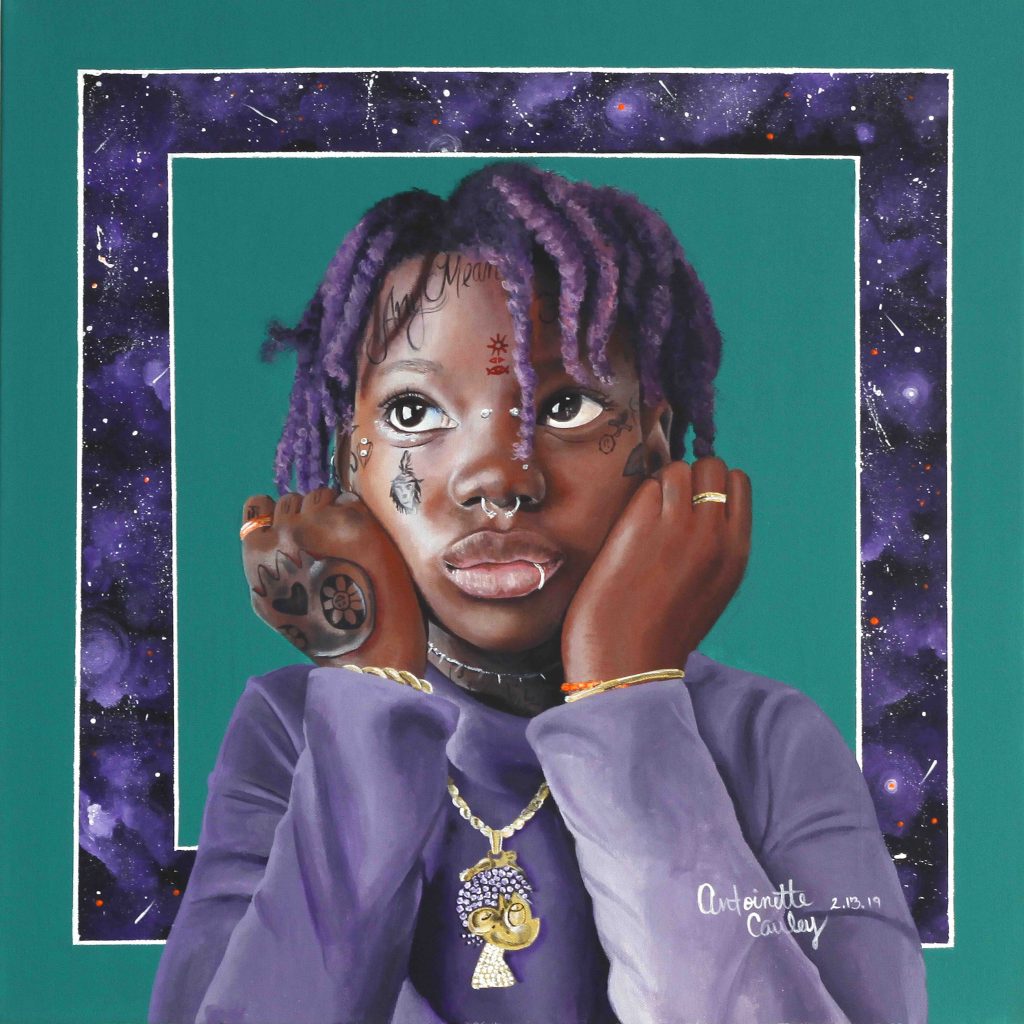

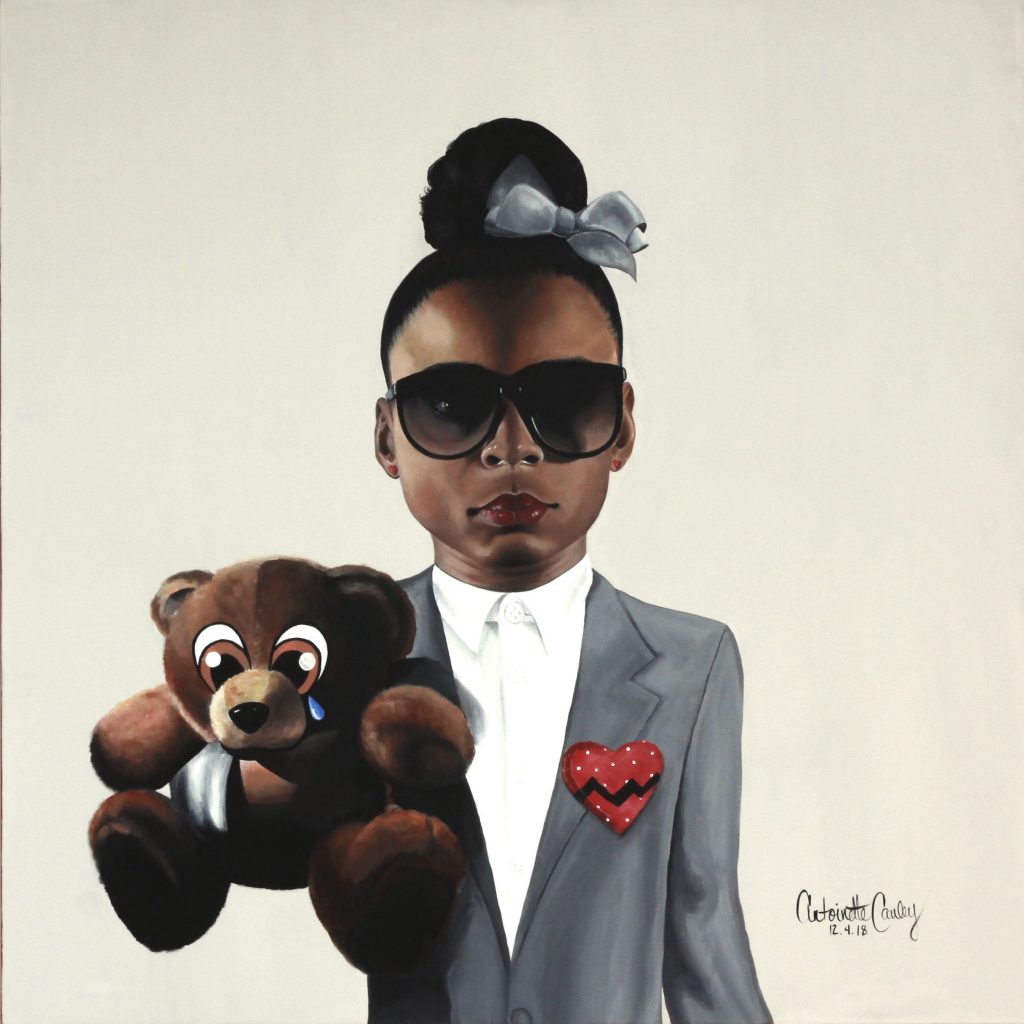

Now known for her portraits of girls embodying rappers and hip-hop artists, Cauley burst onto our radars in early February when she earned first place in Artlink’s 19th annual juried exhibition with her painting “Excuse Me I Have On Too Much Jewelry.” Despite the sudden acclaim, Cauley has been preparing herself for artistic success since childhood.

She credits a family history of artistry, a feverish working style, and a relentless drive to achieve anything and everything she sets her mind to. Four to eight hours every day of her early adolescence were spent making art, building up a base of support with her drawings of celebrities and basketball stars. So while it may seem like Cauley is happening all at once, it has taken years of hustle for her to get here.

Meeting the artist in person takes you away from that hustle. Cauley exhibits a grounded calmness that can only be mastered by those who have lived through chaos. Her positive demeanor belies a history of conflict, anxiety, and depression that makes you wonder why those who have been through the worst often seem like the best people.

Cauley’s childhood was defined by her parents’ tumultuous relationship tossing her between west, south, and north Phoenix. Her mother and father, white and black respectively, separated when Cauley was young. Along with her younger brother, she was ripped away from her Latino and black friends at Orangewood Elementary in west Phoenix mid-semester to be dropped into a classroom filled with white, upper-class Paradise Valley students at Shea Middle School. Then back again months later.

Cauley learned different cultures, dialects, and vernaculars in order to survive between disparate worlds. She adjusts her language seamlessly and authentically depending on who she’s around, and her adaptability results in her exhibitions being attended by her black friends from south Phoenix and her white friends from the suburbs, along with gang bangers, teenagers, family members – all the way down to her therapist.

Growing up, summers were spent with her aunt Julie Ann Robinson Roy, who was Cauley’s first mentor in the arts. Every day Cauley, her brother, and her cousins were immersed in a new project and encouraged, no matter how tacky their creations looked. Cauley took her aunt’s reinforcement to heart and strived to model herself on how she saw her mother’s sister – pure love and light in human form.

Cauley was devastated by her aunt’s breast cancer diagnosis, and then death, when she was in sixth grade – traumatized by the loss of a woman who was her second mother – and terrified believing it would happen all over again when two months later, her actual mother was diagnosed with the same disease.

Cauley was too young to process all the things happening around her, so she hardened herself against her aunt’s death, the shuffling between schools and friends, and her mother’s descent into medicationand emotional unavailability. Almost overnight, Cauley dropped her notions of childhood and stepped up to take on an adult role in her family. Her mother’s battle with cancer ultimately brought them closer, but other hardships compounded and drove the two apart.

To combat that childhood trauma, Cauley retreated into her art, which became her sole source of stability for years. She has also battled with anxiety and depression into adulthood, painting her way through bouts and still suffering panic attacks to this day. In the end, she is thankful for all her struggles, saying they made her self-reflective and analytical, both key to making and maintaining her current success.

Cauley often says her work is defined by growing up too fast. Once she got into high school, she’d had enough and dug in her heels. Even though it resulted in three-hour-long bus rides, she insisted on staying at Tempe High School, and refused to bounce between her parents. She also picked up a job at a Boys & Girls Club after spending a year’s worth of after-school time there.

The job introduced her to two black artists, the men who ran the Ladmo Branch, who helped her take the first steps toward becoming a teaching and working artist. Cauley worked there for fourteen years, leaving only two years ago to pursue her art full-time. While she was happy to leave, the Boys & Girls Club left a tremendous impression on her. She felt a sense of obligation during her time there to continue the work, but in a different form that arose when she coupled that sense of obligation with memories of her late aunt.

The J.A.R.R. Initiative, a program named after her aunt, embodies the purpose of giving kids the same experience Cauley had enjoyed every summer as a child. Running three years strong, J.A.R.R. offers mentorships, field trips, studio visits, and one-on-one training for aspiring teenage artists. Kids learn the business behind the craft, be it music or visual arts, and spend time with professionals. Cauley’s goal with J.A.R.R. is to help “create the next generation of black and brown artists in this city.” She wants the initiative to promote fine arts in underrepresented communities and fill the gaps she’s seen firsthand in arts education, representation, and accessibility.

After the Boys & Girls Club, Cauley took the plunge into the art world, staging her own art shows independently until monOrchid Gallery took notice and picked her up. From there, she has hit the ground running. In March alone, she opened her solo exhibition, created and ran a panel with women in the arts, coordinated a femme empowerment workshop, launched J.A.R.R.’s first twelve-week art and entrepreneurship program, and hosted a handful of private art events curated around her exhibition.

It was only fourteen months ago that Cauley embarked on her first serious body of work and stepped outside her comfort zone – of celebrity portraits that won her a quick and easy fan base – and into a series that transitioned her into less comfortable and more introspective subjects.

A quick look at her portraits of young girls embodying rap artists might not seem to convey emotional depth, but the longer you spend with each painting, the deeper you go. “Nothing has ever felt more right to me than painting a girl with face tattoos,” Cauley ruminates. She wants to help viewers understand this and has produced a soundtrack on which her exhibition, Ain’t Nobody Prayin’ For Me, was based.

While she enjoys all types of genres, hip hop and rap connect her to her family and past, and also motivate her forward. 2Pac has had the greatest impact on Cauley and her parents, but she is also heavily inspired by Nipsey Hussle and J. Cole, who have made appearances in her paintings. She sees them as contemporaries of a sort: black artists who shatter stereotypes, balancing gangster lifestyles with improving communities and speaking out on crucial issues.

Cauley is through and through a black artist. The label is critical to her artistic identity – she does not refer to herself as a biracial artist, or a half-black, half-white artist. She makes this distinction to promote the representation of black people – and black women particularly – in the arts, while identifying and challenging colorism in the black community. It was not a simple or thoughtless decision for her to make, as she has grappled with labels and identity in the face of race and the arts, and has come to embrace her blackness as much as her biracial-ness.

It is easy to assume stereotypical representations of her parents based on their race. Her mother came from a Mormon family, with lots of siblings; family members sported big houses in Mesa, Utah, and California. “They go to church on Sunday and say ‘oh my word’ all the time. That’s my favorite phrase from them,” she jokes.

Her father and his family, all Phoenix natives, are “super hood; everyone had kids when they were fourteen, everyone’s on welfare… half of them don’t have jobs,” she says.

But while these lived-in stereotypes existed, her parents lived beyond them. Her mother adored hip hop and rap, and was the first in her family to not go to college, while her father remains a talented three-dimensional artist, woodworker, and welder. Both sides of Cauley’s family intermingled regularly for shared family functions and summer stays. The characteristics that seem unconventional from a societal lens were normalized to her at an early age and are represented in her artwork with pride.

Cauley is unapologetic: about her art subjects, her taste in music, her grills, her diva personality, and her drive. She’s mindful of being perceived as the angry black woman but isn’t afraid to say that when it comes to her favorite music, “throw some gunshots in there, and some sirens, and I’m a happy girl.”

She also uses her racial fluidity to motivate people who look like her or are growing up the way she did to push beyond the current culture that constrains their stories.

“Statistically, I shouldn’t be sitting in this gallery right now, preparing for this huge show,” she said one week before the opening of Ain’t Nobody Prayin’ For Me. “I should have five kids and be on welfare, maybe have a drug addiction, I dunno. But I chose to break the cycle, and if I can do it, anyone can do it.”

She knows that despite this, that however she presents herself, many people will view her as capital B Black – in the ignorant sense of the word – and nothing more. Though it is not possible to fully escape the consequences of racism in America, Cauley demonstrates how to take control of your narrative using more than luck. She also knows representation is critical, but can’t solve everything.

If painting fivepaintings in sevendays doesn’t seem like enough, Cauley is also creating as many hands-on opportunities as possible for black and brown girls, teens, and women. She is a motivational speaker, mentor, panel and workshop host, producer, and director, leading by example to help others.

Cauley hopes her art and messaging will make a lasting, positive impact on her community and in the lives of people all over. She strives to be represented in galleries everywhere, but maintain her hub in “nitty and gritty Phoenix.”

Get a deeper look into Cauley’s life and exhibition on April 19 when she debuts her autobiographical documentary Somebody’s Prayin’ For Me at monOrchid.