Religiosity has shaped people and cultures of the world in uncountable ways, both subtle and profound. But for centuries – perhaps even for millennia – criticism of organized religion was a crime warranting extreme punishment. George Bernard Shaw is credited as once stating, “The heretic is always better dead. And mortal eyes cannot distinguish the heretic from the saint.”

Thankfully, in much of the free world during our own era, artists are free to produce work that is provocative and critical of organized religion, without having to worry (too much) about facing retribution like public humiliation, stoning, castration, or other brutal forms of punishment popular in the time of the crusades.

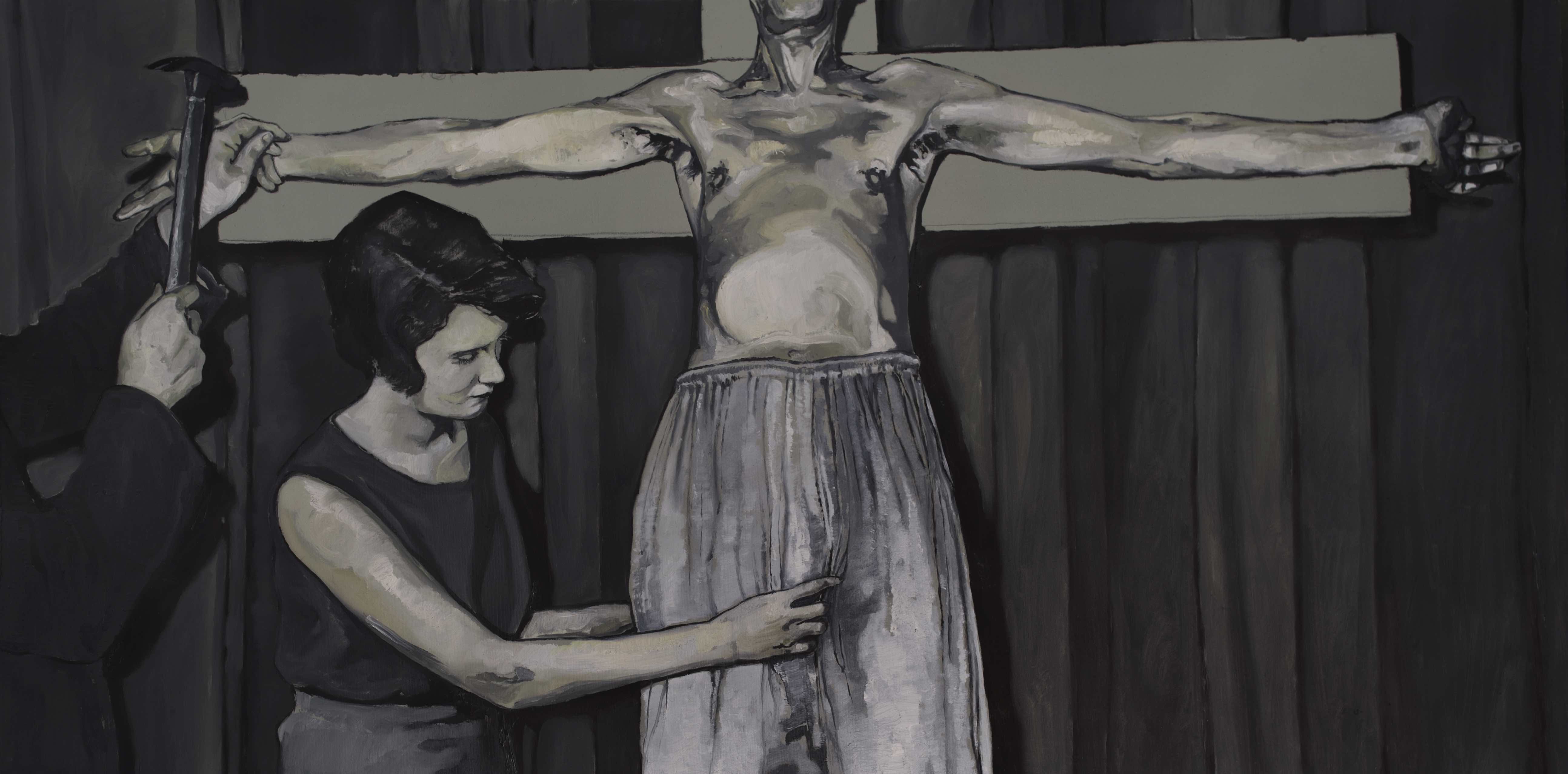

Painter Eric Kasper has, in the past, had to face the mob for works he produced that some critics deemed offensive. Several years ago, his art was removed from a show – blatantly censored. Yet Kasper persists in producing and compiling images that draw out dramatic responses from some viewers. “This is probably the scariest thing I’ve ever done,” Kasper says of his upcoming show, Belief, opening September 16 at the Eric Fischl Gallery at Phoenix College.

Kasper explains that while he likes to leave his paintings very open to interpretation, because there is a religious theme to the work in this show, he has a slight concern that he may be personally attacked. Kasper says he isn’t anti-religion. His images are meant to induce deeper thinking on religious and cultural subjects and perhaps inspire some conversations about why we do “what we have always done.”

“In my old job, this lady who billed herself as very Christian – she must have thought I was struggling or something – lent me this movie called The Secret,” he says. “I watched the thing just because she gave it to me, and it’s all about financial prosperity and material gains. It is the most backward-thinking thing I have ever seen,” he says.

The message of The Secret is basically that through prayer and positive thinking one can will almost anything one desires to come into being. But the examples provided in the book and the movie are mostly material things: a fabulous house, a Lamborghini, posh clothes, extreme wealth. The emphasis on materiality seems to clash with other Christian values, such as selflessness, service, thankfulness (for what you have), and compassion.

What may be initially most striking about the work in this upcoming show is the scale. Most of the paintings are quite large – so big, in fact, that Kasper plans to remove several of them from their stretcher bars while still in the studio and then reassemble the canvases in the gallery. This is the only way he can transport works this large.

For example, one of the newest pieces, “Abundant Living,” measures about ten feet tall. “I was on a ladder for about three months, which was not easy!” he says. The image is of an opulent bedroom, and it took Kasper about three months just to paint the ceiling. He spent five months working on the painting, total, and says he still doesn’t feel like it’s completely done.

The room was inspired by a bedroom inside the Hearst Castle in California, Kasper explains. A scan of the space in the painting detects spiritual and religious objects and images. Kasper first encountered the image of the room in a book about the castle – he spends a lot of time researching images at public libraries.

On a recent road trip up the West Coast with his partner, Kasper happened to pass the area of San Simeon where the Hearst Castle is located. Out of Kasper’s interest and research, they decided to take a peek for themselves. Kasper describes being highly impressed with the collection – and with Hearst’s eccentricity. He had entire ceilings of ancient European buildings taken apart, flown to California, and reassembled just to make them part of his opulent home.

Kasper was able to visit the bedroom that inspired his painting and see its intricate ceiling. As a painter, the ceiling had been challenging for him. The backgrounds in his paintings tend to be dark and flat, but this was very detailed and complicated.

Within “Abundant Living” are three small paintings-within-the-painting. The bedroom is also decorated with a number of curious and oddly placed objects. One of them is an ancient Sumerian sculpture, “Ram in the Thicket,” named after a Biblical passage by the British archeologist who discovered it in the early 1900s. Placing some of these objects in the room calls into question the foundations of human knowledge, and suggests the subtle ways that religious influences tend to alter our interpretations of the past and of ancient objects, even nonsensically.

Other remnants from days gone by are also on display. There’s a goldfish bowl full of red wine, the fish resting in a clear plastic bag, yet to be transferred to their bowl (a home or a prison?). The three paintings in the room don’t seem to go together at all – each nodding to a different era in art. However, Kasper has shifted the tone and content in minor ways that allow the images to pay homage to the originals, while also somehow speaking/resonating in tandem or in conversation with the others.

In the foreground of “Abundant Living” is a nude man lying on a bed of nails, his erect penis in hand. Kasper always liked the idea that a bed of nails represents something dangerous, thrilling, and impossible in a child’s mind. But at some point, through experience, the adult mind figures out that the danger of the nails is only an illusion.

Kasper says his process of combining or juxtaposing imagery within his paintings is fluid and that he enjoys allowing it to be open. “The whole thing is meant to be dissected,” he says. “Nothing is by accident, but I can’t say, from the beginning, this painting is going to be about this.”

Whether unintentionally or overtly, the artist is inviting people to comment, react, and respond in a climate and culture that often shushes artists when it comes to any form of expression that might seem critical of organized religion. Kasper says that he “lived through the 1990s” and experienced a moment in the U.S. when the Christian majority seemed very vocal, defensive, and even territorial. The paintings are an exploration of this mentality and provide a response and another way to approach conversations related to religion.

In the painting “Milkbelly,” six men are seated around a coffee table, each with a glass of milk. The men are doubled over, covering the backs of their heads with their hands as if awaiting some kind of punishment. A cross with a crucified Jesus hangs on the wall behind them. The room is drab, looking like some kind of church lobby or holding cell. It’s actually an image from the 1960s taken from Life magazine,Kasper says. As mundane as the background looks, the men were reenacting a serious situation – possible fallout from a cold war–era missile. But in their mutual act of sheltering, there is something spiritual – a kind of penance – that seems to be taking place.

An untitled work shows a child at a table who appears to be praying to a fish, standing up on its tail. This image is tied to one of the paintings on the wall in “Abundant Living.” Kasper says he’s still working on this one. “I can’t stay interested in something for that long,” he admits.

Another newer painting shows two figures, one male and one female, who seem to be reclining on a picnic blanket. Kasper says he likes the way there seems to be a religious law between the man and woman. The background is full of abstraction, which meanders – a stark contrast to the very controlled painting of the squares on the picnic blanket. Kasper says he just had to start this painting and give himself some freedom to play with abstraction, after the controlled hours that he spent on the cathedral-like ceiling in “Abundant Living.” This painting seems to light up; it contains a lot more golden tones than most of the other darker works – which are more grays, blacks, and army greens.

Kasper has been working out of the same studio space for more than four years. He opened his doors to the public for Art Detour, but he doesn’t make it a habit. He prefers to remain low key and a little off the grid. He comes from a family of men who did sheet metal work – his grandfather, father, and brother – and that’s what he used to do before he decided to commit full-time to art. Sheet metal was good physical work, he says. But on the other hand, it would wipe him out, and he’d have no energy left for art.

In the sparsity of some of Kasper’s images, a certain hunger manifests. One can’t help but wonder about the missing pieces of the story that could help explain what appear to be odd or disturbing behaviors. The artist has decided not to spoon-feed the viewer – this leads one to fill in the missing elements through imagination. Sometimes the explanation can be dark, disenchanting – even terrible.

And that is the challenge that Eric Kasper presents to any of his viewers. None of the paintings make an all-out attack on religion. But if the viewer’s eyes and brain choose to interpret them that way, then they can certainly be suggestive of the hidden dangers, lies, and manipulation that go along with groupthink.

Belief, the paintings of Eric Kasper, opens at 5:30 p.m. on September 16 at the Eric Fischl Gallery at Phoenix College. The show runs through October 3.