Artistic vision sometimes examines the big picture, but other times it focuses on the microscopic. The scope depends on the artist’s lens through which we are invited to glimpse the world. The elements an artist focuses on depend on their mood, state of mind, and place in life, as well.

Christine Cassano recognizes that her work is often deeply connected to her own journey, self-reflection, and internal and external processes. In a show of new works, “Litmus,” on view at Gebert Contemporary, Cassano organizes smaller swatches borrowed from one great, complex, delicate and fragile ecosystem and fine-tunes the focus to examine its blemishes. In this case, that big-picture system is Mother Earth, and the blemishes are all micro-aggressions, patches of damage and destruction appearing on her virgin skin that have been put there by human activity.

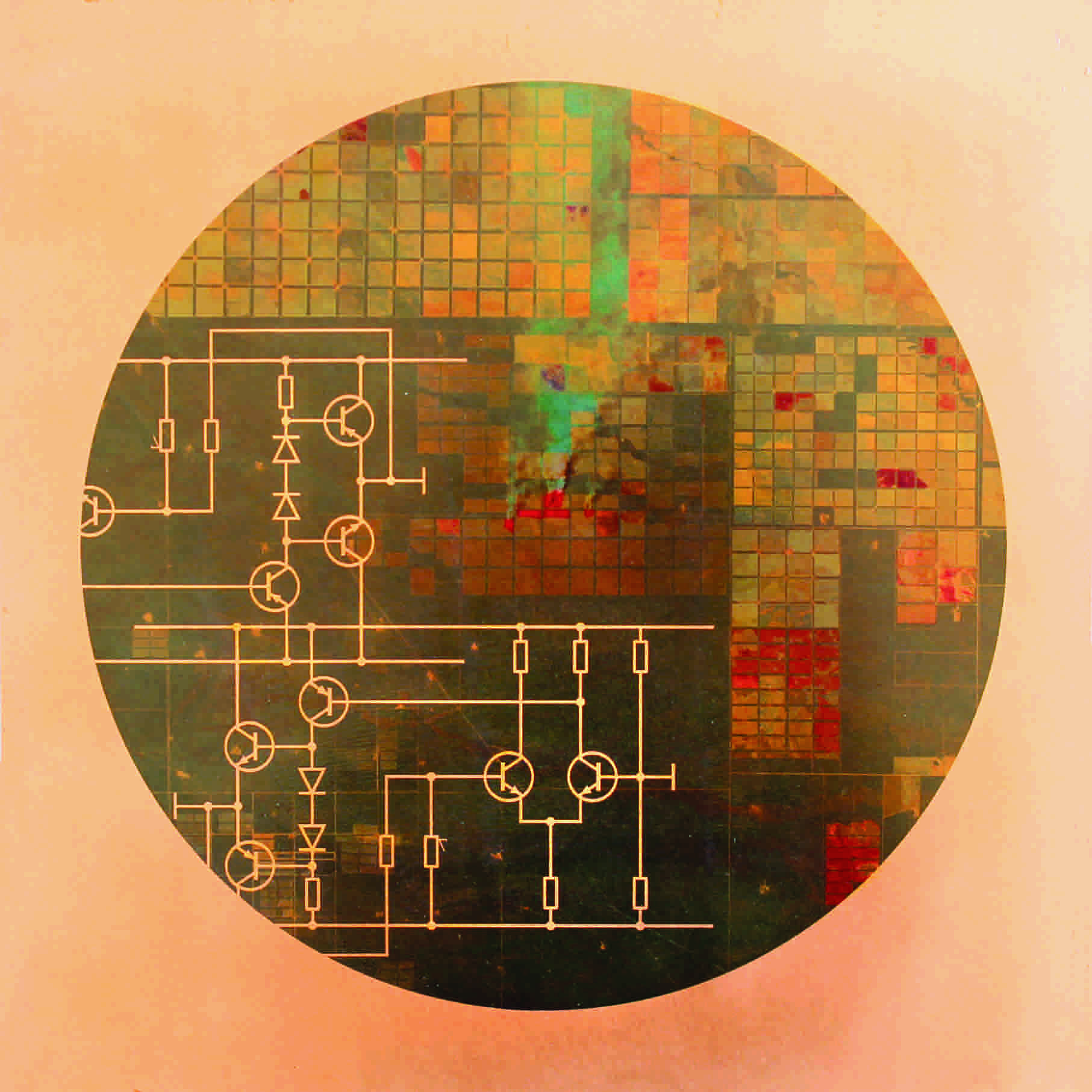

“Litmus” features copper and aluminum plates with satellite images of topography, circuitry, and aviation charts printed on them. One wall of the show features a 10-foot installation comprising more than 500 sections of aviation charts imprinted on circular fragments of copper that float on pins. The round images on copper intermingle with small mirrors. Cassano explains that the mirrors are meant to suggest self-reflection for the viewer, as in, what is our role in all of this? How are we responsible, or are we complicit?

Cassano’s brother Allen is a commercial pilot who has prior Marine Corps experience. He is the one who provided her with his old flight charts. The other personal part of this work was that Cassano reconnected with one of her father’s closest friends, Bill Readdy, who worked for NASA – a man known to Christine and her brother as Uncle Bill. Readdy was her father’s squadron pilot and a very close family friend. He was there the day they lost her dad. Cassano’s father was a fighter pilot; he died in a training action in Puerto Rico due to mechanical failure resulting in a plane crash.

Uncle Bill was around a lot at the time to console and help heal the family. He later advanced in his career, first becoming a test pilot and then moving on to NASA. Now retired, Readdy served as a space shuttle commander for three different missions. This connection reinforced Cassano’s fascination with space and the imagery that informs her new work.

The images from space that appear in Cassano’s work were taken by satellite and are the result of some of the greatest minds and imaginations at NASA. Cassano was able to use them because they are not copyrighted, although she edited them extensively.

This year, Cassano was awarded an Artist Research grant from the Arizona Commission on the Arts. She received the notice of the award last December and must complete her proposed project by the spring of 2019. Cassano applied for the grant to learn new methods and work with new materials. A big goal of hers was to explore techniques for molding concrete and create a large-scale sculptural pour.

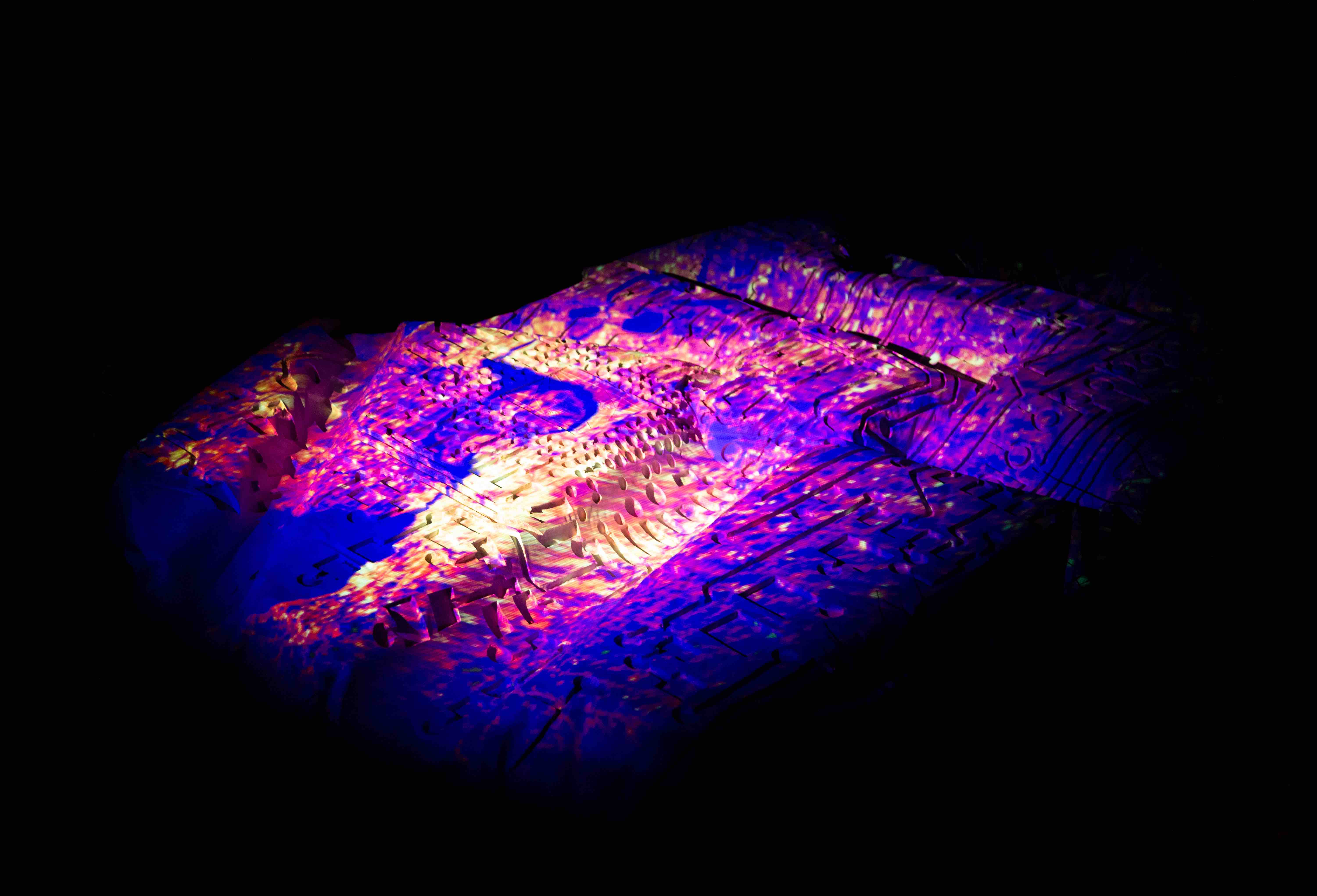

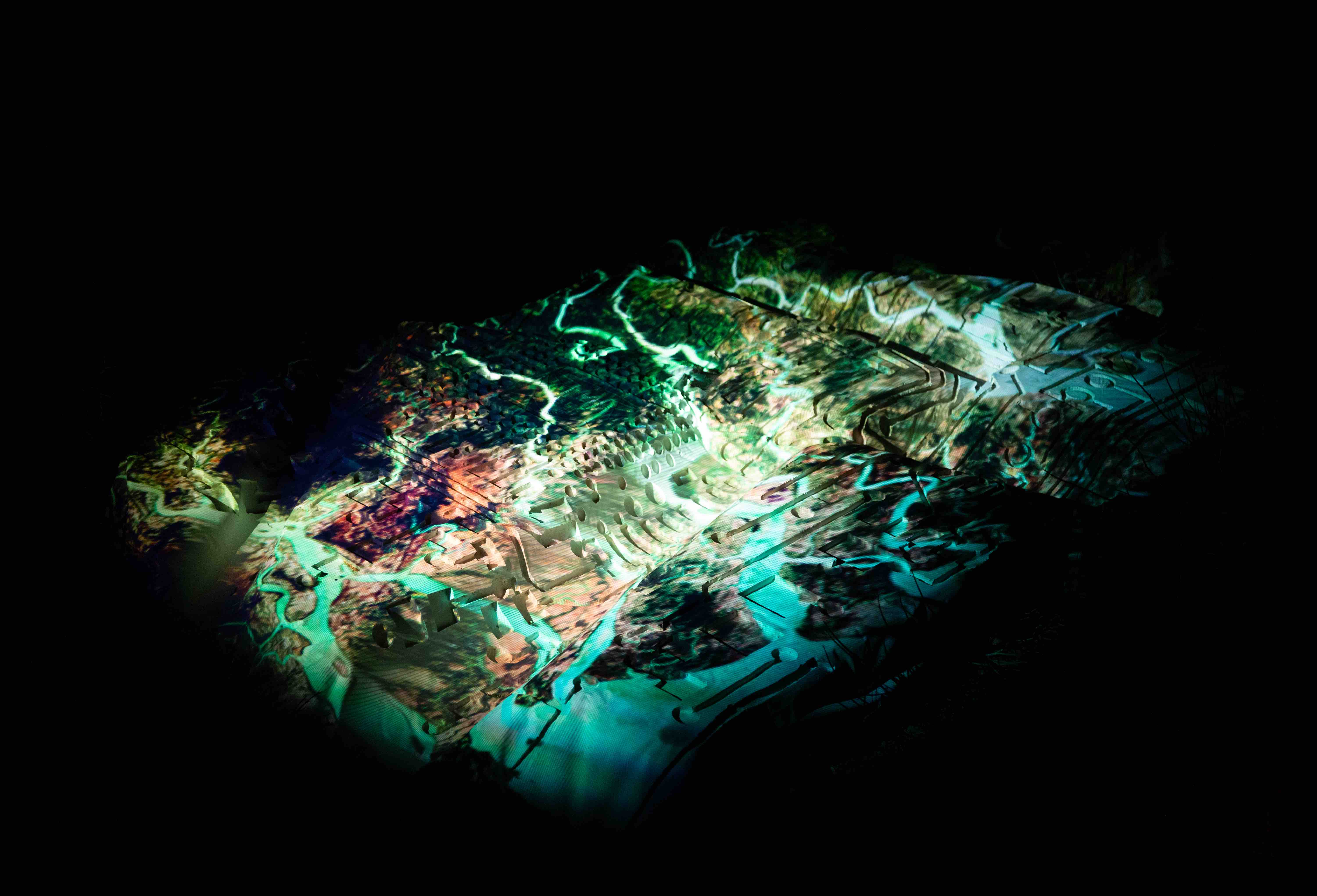

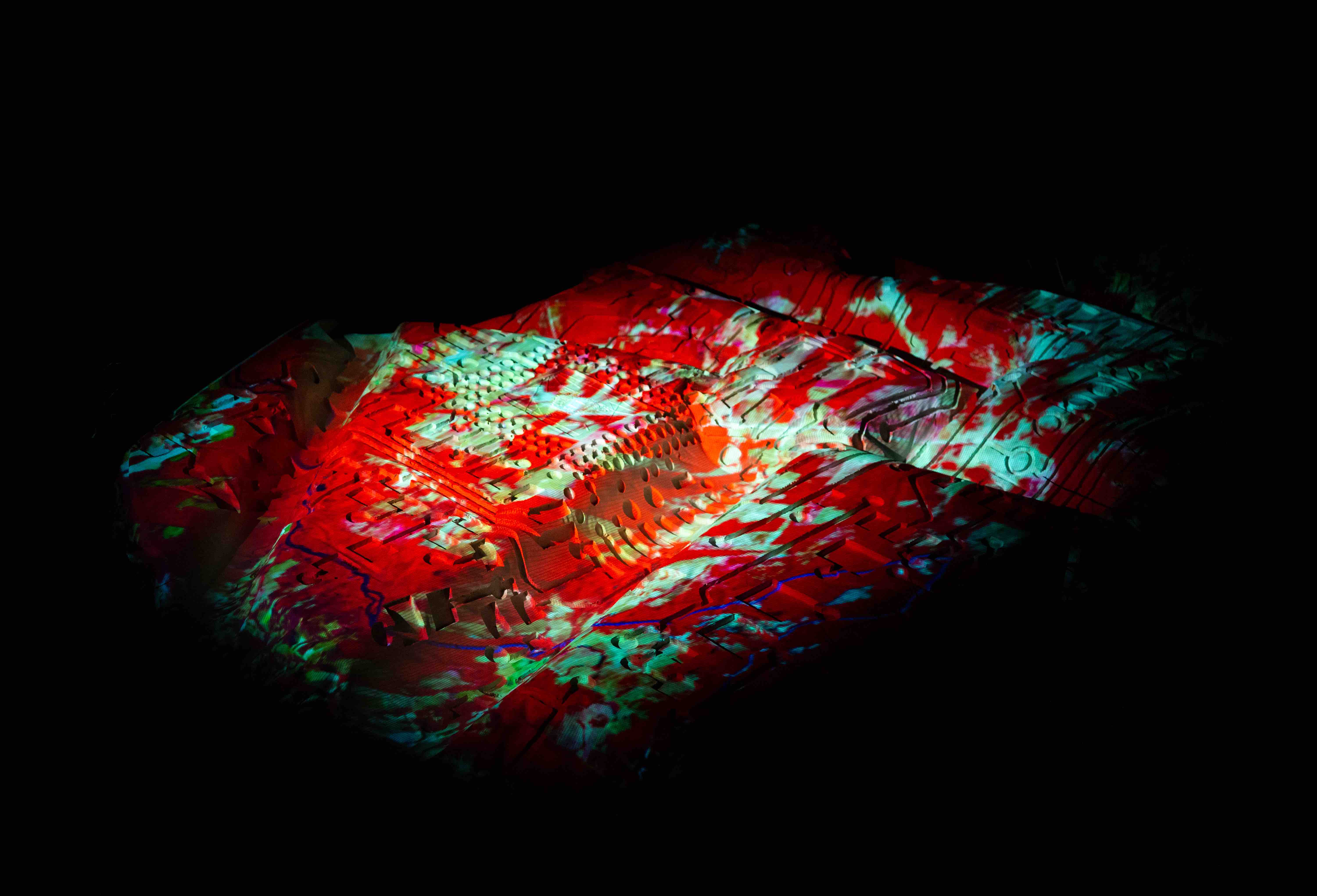

“What I wanted to do was create a sculpture dealing with that pattern of the technology that’s been appearing in my work. Basically, I wanted to have this mega, fossilized-looking piece of electronic equipment in the desert in a remote area and have it set up so that images were broadcasted on top of it,” she explains.

The image of a motherboard has been a dominant form in Cassano’s work for the last several years. She has made variations on this theme, cutting smaller forms from real reclaimed motherboards to form her own networks, connections, and circuits out of organic materials, including woven strands of her own hair.

The research grant piece, “Cache,” is a 300-pound cast concrete motherboard. Cassano, along with some assistants, designed the large-scale mold and then filled it with scrim (a mixture of concrete and fiberglass). The edge of the poured concrete appeared rough, almost like the frayed edges of a textile.

Once the form was made and set, Cassano transported it to Joshua Tree National Forest and shot time-lapse video footage of her collection of blemished Earth images projected onto the form. Tucked into the dark desert night, the images appear on the sculpture as if they have been beamed by satellite. Former Phoenician, now Los Angeles–based photographer Sean Deckert helped Cassano produce the desert time-lapse. During playback of the video, as the day grows to night, the still images slowly appear. And then as dawn approaches, the images slowly disappear.

The still images that Cassano selected represent different visible forms of human impact on the planet that can be viewed from space. They include oil fires in Iraq, deforestation in South America, agriculture in the Sahara, human-caused wildfires, algae blooms from chemical runoff into oceans, and densely populated urban hubs. She edited the images to enhance things like saturation, contrast and intensity for increased effect.

“Sometimes I think what’s interesting about those satellite images is that they are beautiful, but they are also crazy disturbing, when you look at them up close,” she says.

Cassano obtained permission from a group of anthropologists to use satellite Earth-scan images of a previously unknown site of Mayan ruins near Tikal that has been for centuries canopied by the dense Guatemalan jungle. Using a type of aerial scanning satellite technology called Lidar, the anthropologists discovered the sprawling city and located thousands of structures back in February. They estimate this newly discovered site could be the biggest of the Mayan world.

This summer, Cassano took a four-day workshop with well-known concrete pourer and trainer Cody Carpenter, along with 70 attendees from around the world (Cassano was one of only three women in the class). Most of Carpenter’s work is architectural, but for his Plan B workshop, groups explore other purposes for pouring concrete. Carpenter allows the workshop attendees to circulate and share, gravitating toward work on a project that most captures each member’s interest. Cassano describes the experience as interactive and collaborative, a “hive-mind mentality.”

“We all helped each other with stuff, and I was able to take a break from my project and help with some of theirs. I brought the mold-making capacity to it. Most of these guys specialize in custom concrete. So I was the ‘art girl,’” Cassano says. She met Cary Ezell at the workshop, and he invited her to visit his property, Bungalow in the Boulders, in Joshua Tree, where she installed her “Cache” motherboard and began to film the day-to-night-to-day time-lapse cycle.

In contrast to the durability of the enormous concrete motherboard, another work that will be featured in “Litmus” is an enormous construction of glass, metal, and porcelain, an item of utter fragility. “The Gravity of Correspondence” consists of a large mirrored base, 2 feet wide by 6.3 feet in length. The mirror faces the ceiling, like a tabletop. Suspended above are small porcelain “petals” that almost resemble snowflakes – 450 of them. Each piece was hand-formed and is so thin that the edges are translucent and can catch light. These are stacked delicately atop one another, with gravity as their only adhesive, the intricate pattern seeming precious and precarious.

In the past, Cassano has used her work to explore natural things on a cellular level. She’s put a focus on the micro and the internal, honing in on very personal experiences with her body and her own health. At other times she has focused on the Earth and what is buried in the ground. With this show, she delves into the technological and ecological, closely examining man’s impact on the ecosystem. Her work often brings together the four elements: air, water, fire and earth.

Cassano also has acute synesthesia, a neurological condition that creates the sensation of experiencing one kind of sense through another. It is almost like having your senses cross-wired, she explains. For example, she can hear colors. “When I hear music, I see color in a very intense way,” she says. Another sense that becomes crossed is her sense of touch, which can also produce intense sensory overload.

But she’s lived with synesthesia long enough that it’s not a distraction to her work. The special effects operate on their own bandwidth, so, in a way, she’s able to control them and even harness the energy. “When I go all the way in the body and I look at these systems and these cells, I’m really trying to navigate or decode my own cross-wiring,” she says. “I’m so fascinated by systems because mine work so differently.”

“Litmus” is on view at Gebert Contemporary, 7160 E. Main Street, Scottsdale, through Dec. 8.