Paul Mosier believes in the muse. His life story lends serious credibility to its magic, mythic power. Specifically, his development as a writer defies conventional logic in that he isn’t a heavy reader. Most writers are galvanized to write because of an innate love for reading. But Mosier is a writer because, well, he likes to write. It’s as simple and beautiful as that. Mosier is set to release a book with HarperCollins next January. And, crazy enough, it was all beget from a song lyric first recorded by bluesman Junior Parker in 1953. The lyric was, “Train I ride, 16 coaches long.”

It was from this seemingly simplistic phrase that Mosier was able to draw a stream of consciousness that turned into the novel Train I Ride. According to Mosier, he simply followed the muse as it took him on a ride. “All of my experience with how stories begin supports my subscription to the idea of the muse. I like the way that it helps me to have a degree of humility. I’m fortunate that the muse knows my address,” said Mosier.

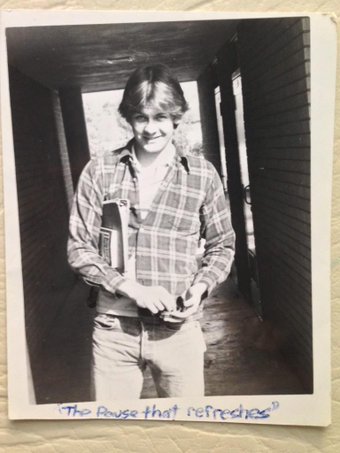

Mosier was born in Phoenix at St. Joseph’s Hospital. Throughout school he was in the gifted programs, and in sixth grade he developed a film script called “Intergalactic Gophers.” Though his parents were not necessarily creative, they were able to provide their kids with the autonomy to create. Mosier’s brother is a cartoonist and his sister is a writer.

By the time eighth grade rolled around and kids began fumbling through the awkward depths of adolescence, Mosier was fumbling around for different reasons. By eighth grade, Mosier was an alcoholic. His reason for drinking was simple: he was afraid of women. “I found that I really liked being drunk because it made it easier to walk past girls without dissolving. I felt that if I didn’t dance with a girl at the eighth grade dance, I would die alone,” said Mosier. He spent the next 10 years or so in a drunken haze. “With drinking I felt like I was strapping myself to a rocket and who knows where I would end up. I had to take LSD on the weekends just so it didn’t feel like a Tuesday night,” Mosier said.

Though some people drink to feel, Mosier felt like it was a means to numb. Once he decided to quit in 1990, there was no stopping the feelings. “I was medicated while I was drinking, and now I’m a feelings junky. My own writing makes me cry all the time. It wouldn’t work to be liquored up or high. The truth of write drunk, edit sober—some people won’t allow themselves to be seduced by the muse until they drink,” Mosier said. Mosier was able to transfer all these new feelings into short stories that he would read to his muses in the flesh: women.

As the saying goes, energy cannot be created, it can only be changed from one form to another, and in that way Mosier used his writing to impress women, rather than hiding behind the liquor. Whether it was the girls at 5 & Diner or the baristas at Dos Estrellas, Mosier made sure that what he wrote was read by women. “It’s interesting that the creative spirit that visits humans is female. They’re just better than us. They’re more charming.”

It was the women he met who were his first audience. He wanted to write stories that spoke to them. However, in 1993 there was a girl who made smoothies at The Eggery in Phoenix who would soon become his main audience. He asked Keri on a date by writing on the cover of a short story he’d written, and she said yes. Fortunately for Mosier, after a period of dating she said yes to marriage, as well.

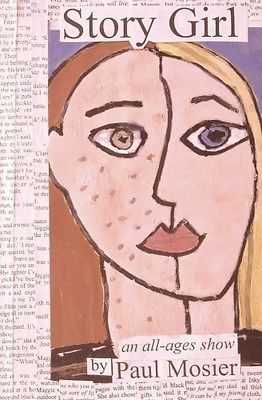

Paul wrote on and off in the ’90s during his marriage. He also made half of his living as a painter. He didn’t write his first novel until November 2011. Up until that point he was mainly a short story writer. However, he decided to try to write a novel for National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo), and he was able to complete it. He describes the process as “hammering away. … I decided to make the protagonist’s pet fish the narrator. I put a line into the fish’s mouth, and it was a good first line and I was chasing after it. It showed me that I could do that and produce something at that length. And taught me that you don’t have to do it all in advance. You see the road as you walk down it.”

Something that really helped Mosier transition into novel writing was the Phoenix Writer’s Group. In the group he was able to meet other writers who could help him flesh out his stories and ideas. At one point he was going three or four times a week to seek out feedback from his fellow writers. One in particular helped him articulate who he was as a writer. Jake Friedman believed that Mosier was a postmodern writer, given his inclination for magical realism and having questionable narrators tell his stories.

Though Mosier might not have had the credentials that some of the other writers did, he had all the work ethic. Once Mosier finished his first novel, he says that he couldn’t help but stretch most of his ideas into novels in one way or another. Whereas a lot of writers agonize about how they are going to write a novel and affix a great degree of weight to it, Mosier has always approached the process very simply. “The most important thing is writing,” Mosier said. “I feel like some people are trying too hard to be prepared to do it before they do it. I think you do better as you do it. When I was an undergrad there was this guy in my hall who would sharpen his pencils and just organize his desk. If you’re supposed to tell stories, just get into it and trust the muse. I don’t think that the muse is going to give you the whole thing at once. Sometimes I write the first line and trust that the next line will come.”

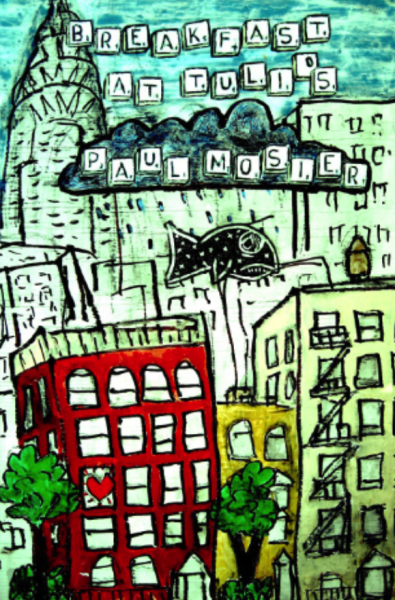

It was this sort of thinking that created the book Train I Ride, which was picked up by NYC-based publishing giant HarperCollins in the summer of 2015. Before that, Mosier had tried to send his self-published book Breakfast at Tuli’s to various publishers, but nobody bit. Once he finished writing Train I Ride, he sent query letters to publishers out of obligation. He was resigned to the fact that he wouldn’t get any hits and that the book probably wouldn’t be published. However, an agent who loved his work and believed in him pitched it to several large publishing houses. Not only did a major publisher want his book, but two of them did. Mosier decided to go with HarperCollins, and months after they struck a deal he found himself meeting with the editors and his agent in New York’s iconic Chrysler Building, telling jokes and talking about his book. Train I Ride is due out in January 2017 and is the first in a two-book deal Mosier signed with his agent.

Despite the incredible high he felt from signing the book deal, Mosier’s life was brought back to earth when he found out in February that his youngest daughter, Harmony, had developed cancer at age seven. What originally seemed to be a rapidly growing overbite was diagnosed as rhabdomyosarcoma. Harmony had to spend nine days in the hospital, but her hopes remained high throughout. Mosier has been touched by the community’s generosity throughout it all. One of the more notable contributions was “Hope for Harmony,” an art sale and reception at Treeo, spearheaded by Stacey Champion, with donations from local artists, which raised more than $5,000.

“Being able to accept the love and support has lifted our spirits to match Harmony’s, which has been high from the start. She would make the doctors laugh when she was in the hospital,” Mosier said. Mosier also talks about the gift of community. Before going through the fight with Harmony’s cancer, he thought the concept of community was kind of hokey, but the love and support his family has received, and the battle he’s seen his daughter put up, have taught him that it’s powerful and true. Harmony’s cancer treatment is going well so far; the tumor has shrunk.

Mosier believes in the muse, and now he most certainly believes in the power of community.

To donate to Harmony’s recovery, please visit www.gofundme.com/ysp6tsfw.