Very many years ago, while visiting the Three Fountains condominiums in Phoenix, I had my first somatic experience with what is referred to as “desert modernism.” Having lived in Las Vegas prior, my exposure to this architectural typology had been brief, as I was largely preoccupied by “architecture as roadside attraction,” as art critic Dave Hickey once decreed, verities of sign as architectural form, oozing through the bogus sunset.

I will be frank, though; I did not realize it was an Al Beadle at first. But aside from my transient obliviousness, Three Fountains represented much of what I imagined an authentic architectural form arising from the desert sands of the Southwest to be. To my gaze, this stark building of muted coloring was entirely composed of lines and shadows, cut with such an exact precision that nothing looked real, and it was perfect.

The desert is often represented by a harsh angularity of surface, mirrored by the landscape it contains with all of its seemingly stark simplicity. However, this representation is quite basic, as it conceals the incredible complexity that lies beneath. While some architects during Beadle’s time were preoccupied with reconfiguring the desert into a form reminiscent of other geographic zones, Beadle was engrossed with developing an authentic architecture that responded to a true “sense of place,” complementing the desert’s natural beauty, rather than suppressing it. Through his skillful nature, what is seen as severe and angular is maintained but refined by a responsive architectural program. Light is captured, controlled and reflected, crafting and framing the building in both its absence and presence. The native landscape is retained and serves to augment the architectural premise.

Beadle’s honesty is reflected through his perfection of building as craft, endearing his influence and legacy over time, as proved from the fervent following he has gathered, even long after his pencil last touched the drawing board.

The Palm Springs Effect

Growing up in Palm Springs, builder Mike Yakovich never dismissed the value of the area’s unique treasure trove of mid-century modern architecture. Appealing to his sensibilities, it became the focus of his diligent crusade, as did, specifically, Beadle’s work. So when the opportune moment came, and armed with an arsenal of construction experience within the genre (including work with Don Wexler on his last steel project), Yakovich, in collaboration with Beadle’s widow, Nancy, and his associate Ned Sawyer, conspired to once again bring Beadle’s pencil strokes to life.

Knowing that resurrecting the much-loved rectilinear idiom that Beadle perfected could prove potentially disastrous, when architect Lance O’Donnell was first approached for help by the team, his answer was an unequivocal no. With a long history of mid-century restorations and remodels for names such as Wexler, Cody and Frey, O’Donnell is quite familiar with the era and, in fact, an aficionado.

O’Donnell’s reluctance eventually gave way to acceptance, upon realizing that his initial philosophical aversion to recreating the work of an icon—one whom he deeply appreciated for paving the pathway of future modernists—was matched by Yakovich’s genuinely deep affection for architecture. Because of this, O’Donnell felt compelled to sit under the proverbial sword of Damocles and fully commit himself to bringing the unbuilt Beadle to Palm Springs.

He relays how important it was to have Ned Sawyer’s direction and Yakovich’s commitment: “We had architect Ned Sawyer, Al’s associate, to guide us along the way. This proved invaluable to moving the process forward with confidence. This project would not have been built if it were not for Yakovich’s steadfastness or love for that home. He had a vision, and through his own sheer will helped us all walk a path to realization,” says O’Donnell.

Restoration Fanfare

O’Donnell recalls that when he started practicing architecture, there was a renewed sense that Palm Springs had an important stake in the annals of architectural history. Preservationists led this effort by rebuilding and reestablishing the importance of iconic buildings, learning from their successes and failures. The “Kauffman effect,” referring to the well-known Kauffman renovation of a Richard Neutra house in Palm Springs, helped illustrate that a sensitive approach, adhering to the original character and intent of the building, was feasible.

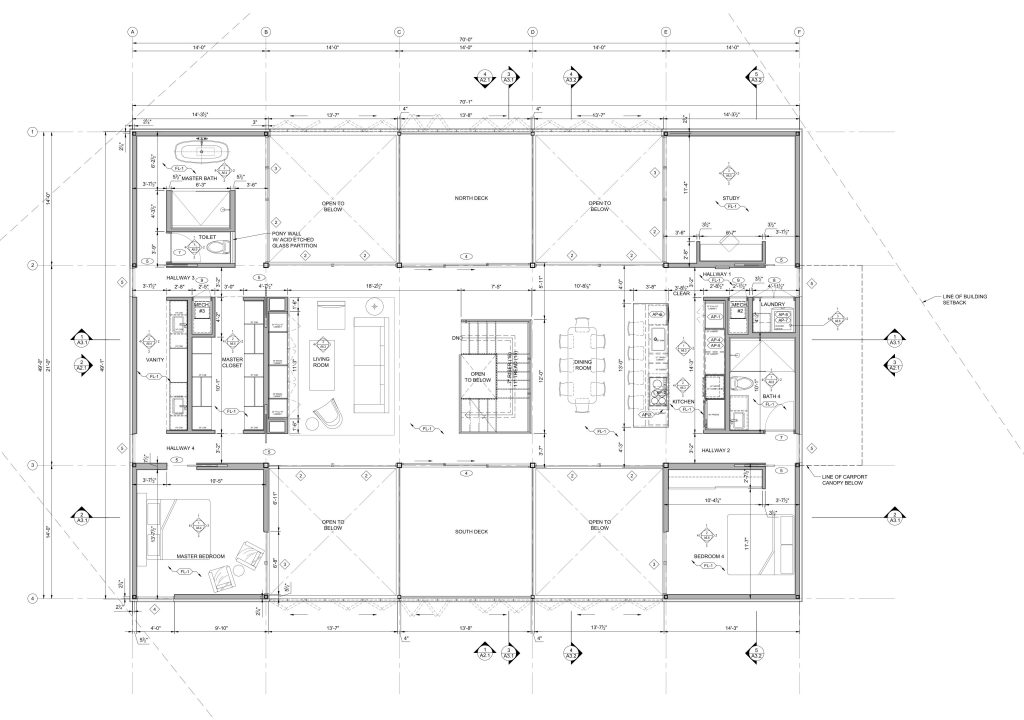

For the unbuilt Beadle, however, current building code restrictions, in combination with modern living sensibilities, proved challenging to adhere to without tweaking the plans. Sympathetic to certain societal proclivities with respect to how people presently dwell, O’Donnell accommodated as needed. For example, the kitchen was on the original plans as a minute appendage of a much larger space and placed off to the corner. O’Donnell instead included it as a prominent part of the loftier open-concept main living space. During the mid-century, kitchens were not so liberally accommodated. O’Donnell relates, “If Al Beadle were alive today, he wouldn’t have placed the kitchen where he did in the ’50s and ’60s.”

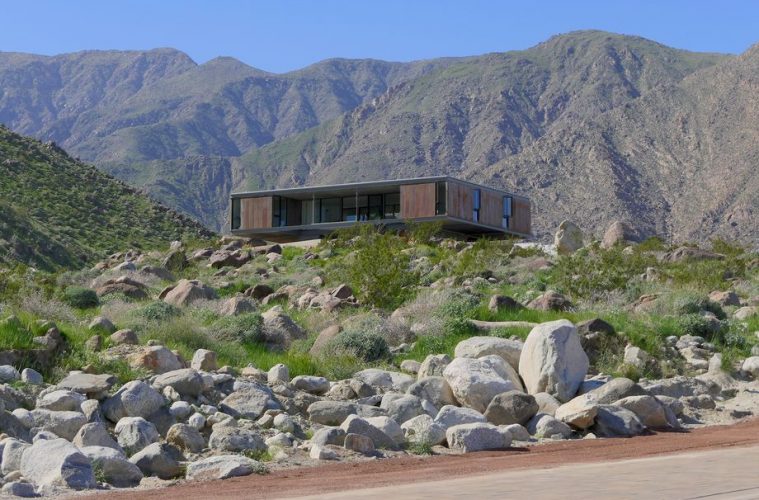

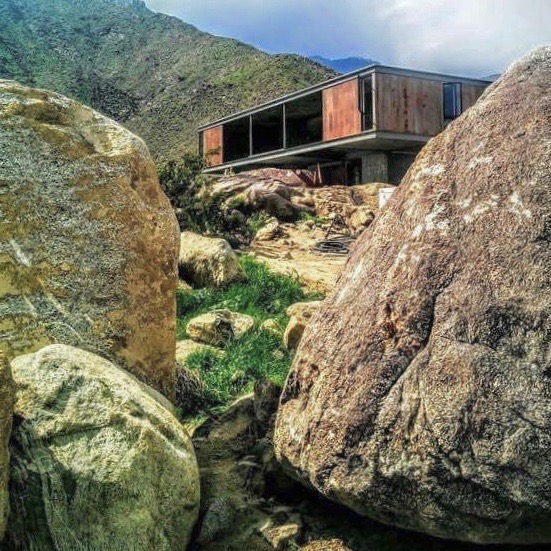

The site itself was purposefully chosen, balancing the ideal mix of light and wind, maximizing views and balancing geometry with the natural landscape. This heady symbiotic relationship between the elements situated the house on a familiar axis, with expansive windows at a southern and northern orientation and minimal glazing on the east and west sides, which would receive the bulk of the intense summer heat. Composed of a delicate balance of expansive glass façades, exposed structural steel and concrete, this material palette was indeed de rigueur of what one would come to expect of a Beadle. In contrast, the velvety corten steel panels depart from this, fashioning a unique twist that simultaneously updates the look and speaks to the desert surroundings by mirroring and abstracting its reddened pigment.

Typical of Beadle residences, the landscape is tied closely to the geometric detailing of the building itself. Often this would include any accessory “objects,” forming an extension of the main house—most commonly, pools. Aware of this, O’Donnell was not enthusiastic about the prospect of visually detaching the pool from the house, but he and Sawyer were profoundly aware that the site, and where they had placed the structure, wouldn’t allow for a direct, inclusive relationship. Here, landscape dictated the placement of this element, breaking away from Al’s customary orthogonal processes; situated at an acute angle from the house, creating a less than ideal relationship between the two major elements.

The greatest trial yet came when harmonizing the design that put a premium on supple proportions and a strong connection to the outdoors via floor-to-ceiling glass, while providing a system that would meet stringent structural requirements, as demanded by the home’s proximity to the San Andreas Fault, some four miles due north. A more robust structure to address any concerns was provided, while retaining the form’s horizontal linearity.

Resistance to raising the ceiling, conversely, proved more difficult. From O’Donnell’s perspective, the house is not merely a composite of floors, walls and a ceiling, but rather a collection of three walls and an outdoor space. He relied heavily on this principle when defending the original plans. Although the experience when one is inside the Beadle space would justify this, many homeowners and builders habitually rely upon a common trope that higher ceilings translates to a more spacious appeal.

“I urge those who feel this [way] to just come in and experience the space. A nine-foot ceiling is going to feel every bit as generous and expressive in Al’s design, more so than a higher height, in a closed box, with a few punched-out windows. Don’t discuss this, just bring them in the house and let them experience it,” said O’Donnell.

From looking at Beadle’s archival drawings, you can tell that he struggled with the predicament of balancing form and structure, personally. In fact, one scheme developed for the house utilizes a cantilever system, which is most interesting to O’Donnell. Beadle was proposing to appropriate a cable-stayed structure (commonly found in bridge design) by taking the four main structural columns up through the roof and cantilevering the building, thus allowing the floor framing to be elegantly waif-like. O’Donnell comments:

“That is not a design direction we took. But if we ever do this again, it might be another possibility to try, because we could take more structural economy out of it. His archive had both—the one we applied, and the other one that was more daring and interesting. Maybe that would be an Al Beadle 2.0.”

Effie Bouras is a sometimes wordsmith, but mostly an engineer with an architecture penchant, and has created a traveling exhibit about both titled, “Considering the Quake: Seismic Design on the Edge.”

Images courtesy of O2 Architecture