“I grew up in a very rural part of America, you know, the Midwest,” painter Brian Boner says. “When you have kids, you have this baseline of, ‘Well, this is how I grew up, maybe this is how my kids will grow up.’ But my kids are growing up in a city in the desert, whereas I grew up in a small town in the forest.”

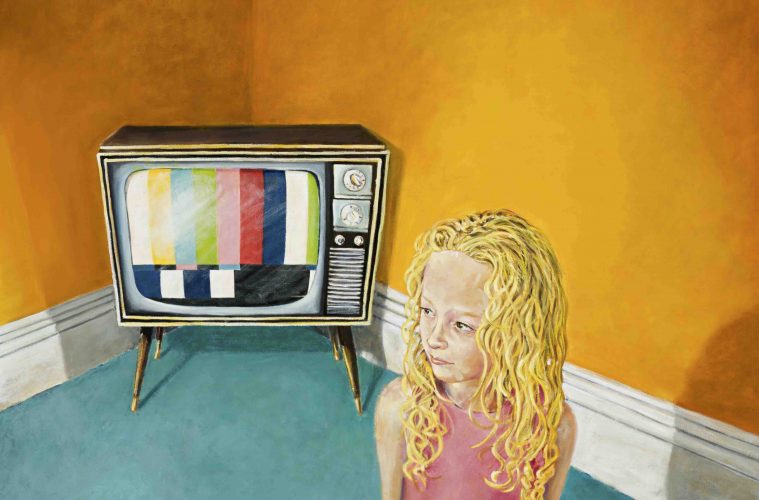

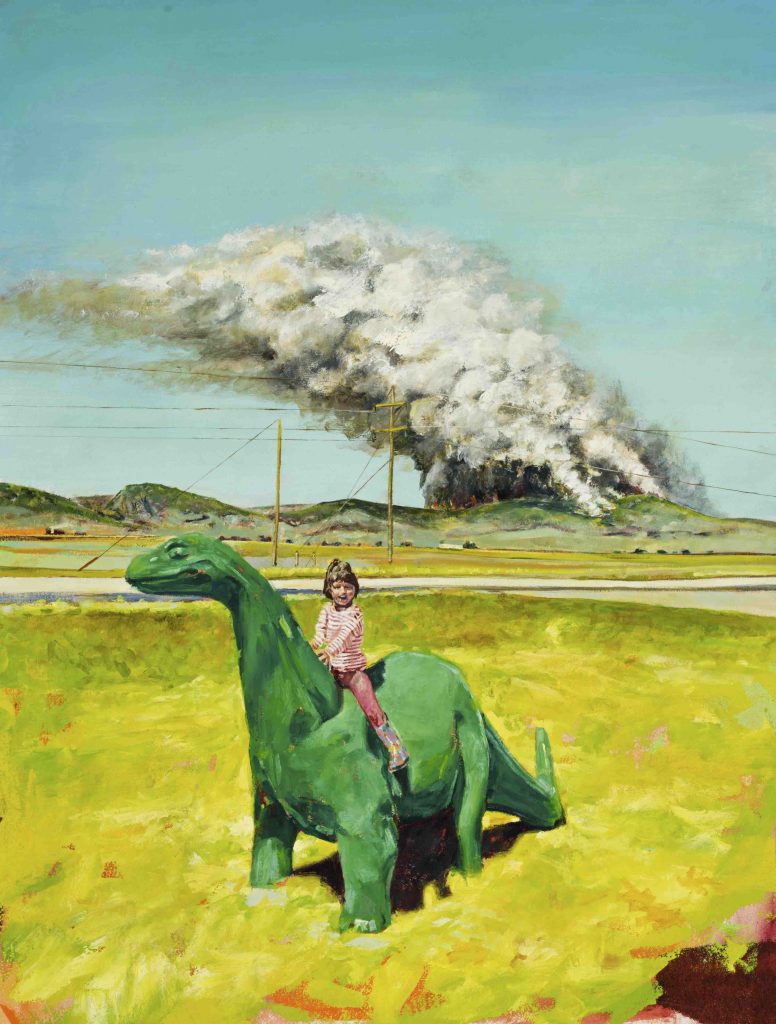

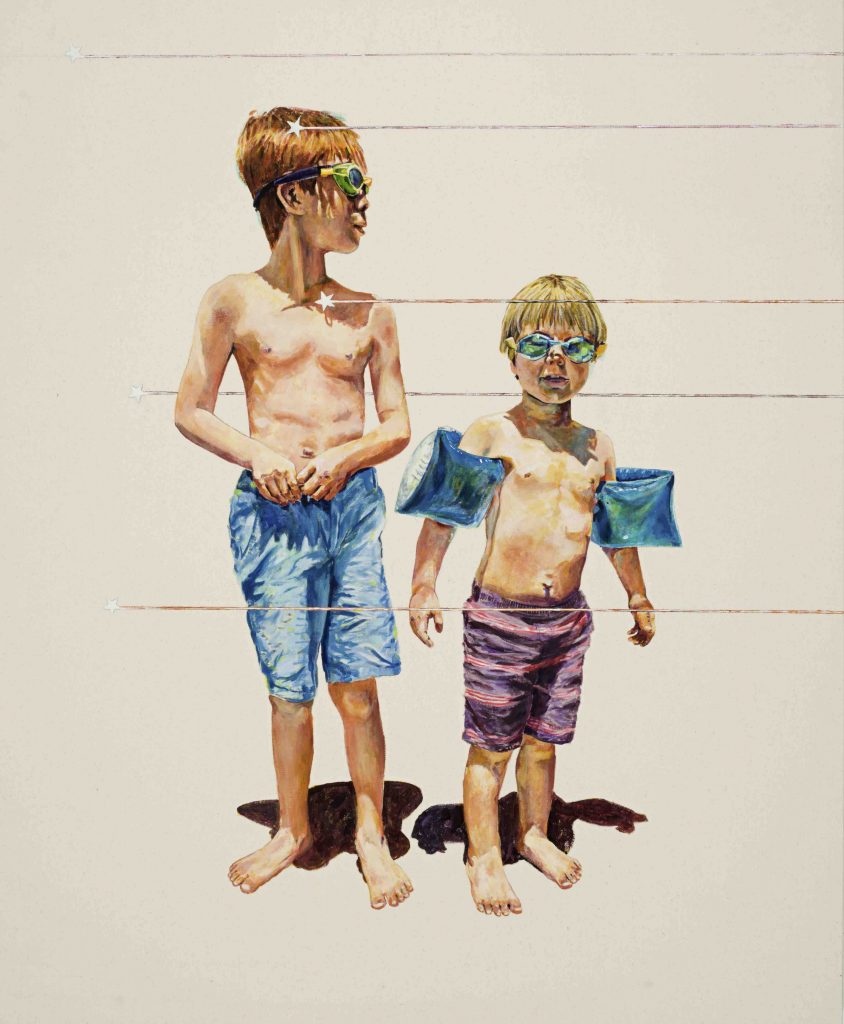

Boner’s new collection of paintings, American Playground,combines contemporary images with some family photos, and also images symbolic of his childhood and the new world he is experiencing as a father, with his two sons.

Boner grew up in Rapid City, South Dakota, near the Black Hills, a town he describes as “small, but not horribly small.” He went to college in Minnesota and Montana (got a bachelor’s in painting and drawing), and he says after too many days of 60-below winters, he had to move on to someplace warmer.

But critical geography is not the only big difference between Boner’s childhood and that of his sons. After college, Boner and some friends moved to Tempe. He used to visit his grandparents there with his family in the winters, so he was familiar with the terrain. Once he started getting into the art scene, he moved downtown.

“I met Greg [Esser] and Cindy [Dash]. They were renovating a house on 6th Street,” he says. “My studio was a garage that you could open from both ends.” While living in the Roosevelt arts district, Boner met his wife-to-be, artist Christina Ramirez, at the Long House. Boner worked for Phoenix Art Group about two years and became further connected with local artists. Then, he supported himself solely from the sales of his paintings.

“I’d pick up the odd job installing things, for Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art or various galleries. Or I’d pick up a job teaching art for a couple of days.” But when the economy turned sour, he found himself in the position of needing a day job again. Through a friend, he signed on with Art Solutions, fine art installers. He’s been with the company more than 10 years and says he likes the work and the flexibility. He was able to take six months to paint full-time in order to prepare for this show.

Some paintings are still lifes – a handful of alphabet magnets, an image of a Jackelope – while others combine imagery taken from a variety of sources in a sort of collage of new meaning. One painting shows his youngest son, Elias, standing before an American bison. The bison appears to be about to drink water from a blue plastic kiddy pool. In the background is the white house his father grew up in, and a barn wall painted with white and red stripes, emblematic of the American flag.

Another painting shows a collection of antique school desks that seem to drip with electric colors (some hidden purples, corners of green) as if emerging from a dream of nostalgia. Boner says these desks were discovered in the attic of his family’s ranch in South Dakota. They came from the old schoolhouse that used to exist miles down the road. How they ended up in his family’s possession is a mystery.

“I come from a long line of educators,” Boner says, listing his great-aunt, grandmother, mother, and father. The idea of handing down family knowledge through the generations is certainly one theme in this show.

Occasionally, firearms and animal predators that are hunted appear in his paintings. Boner explains that his dad was an avid hunter: “He’d shoot anything!” Sometimes there would be big game hanging in the family garage, blood draining and waiting to be skinned by his dad. He tried hunting a few times, but after shooting his first deer, he decided it wasn’t for him.

One of the juxtaposed-image paintings depicts Boner’s older son, Jasper, standing on the walkway to the family’s front door, armed with a squirt gun. Jasper appears to be defending two bunnies who cower together in the foyer. “Guardian of the Innocents” came about after his son asked him one day, “Dad, how do bunnies protect themselves?”

The Americana motif appears in many images, as well, in the use of stars, stripes, and other imagery associated with nationalism. But the message is neither pro nor anti-homeland. It’s a subtle suggestion of the ways our nation has changed from Brian’s generation of children to that of his own. At every turn, there are hints of danger, suggestions that some presence or power might be lying in wait.

These amalgams provide an intriguing dialogue between the pastoral, perhaps of Brian’s upbringing, and today’s real world, one in which his boys are growing up surrounded by screens, with the threat of things like social media bullying and witnessing a burning car in the middle of the street.

American Playground

Through November 21

Fiat Lux Gallery

6919 E. 1st Ave., Scottsdale

Open to the public from 6 p.m. to 9 p.m. Thursdays and other times by appointment