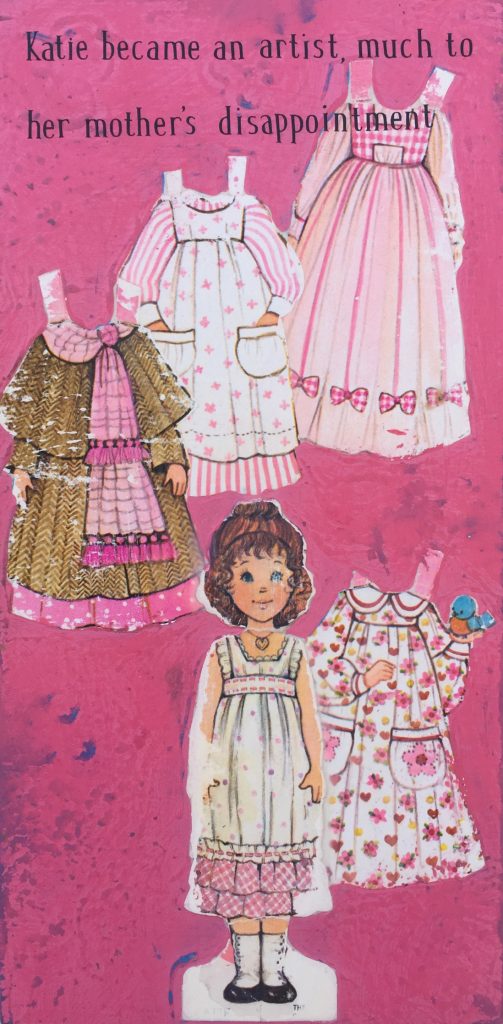

“Katie became an artist, much to her mother’s disappointment.” These words appear in a collage painting by Judith Ann Miller. They describe a shared concern amongst daughters: that the closest woman in our lives is disappointed in our choices. The artist also acknowledges that this intergenerational anxiety plays a part in shaping us, affecting how we view ourselves and our gender roles well into adulthood. The text from that painting, like a mother’s disappointment, stays with me as I walk through the rest of the show.

How will society achieve female liberation? Or any political liberation? Does it start with community action? Or will sufficient introspection free us from imposed social expectations? Judith Ann Miller’s “The Velvet Hammer” exhibition of ironic paintings and mixed media pieces sit with these questions.

This new body of work by Miller references a period iconic for its conservative gender roles: the 50s and 60 – when a woman would be incomplete without a coiffed bob, swing dress, and a husband. Everything from the period’s glamorous fashion and advertising culture to quaint nuclear family dynamics coalesced into a distinct aesthetic that, to this day, is inextricable from our image of the American ideal.

Miller’s bellwether piece Conformation/Control(2019), a vintage dress constructed from period print ads, pairs nostalgia with the damaging expectations aimed at women. The collage dress – with ads warning women to use Lysol as a feminine hygiene product (or else suffer male disapproval) – illustrates how these ideals played a part in policing women’s bodies.

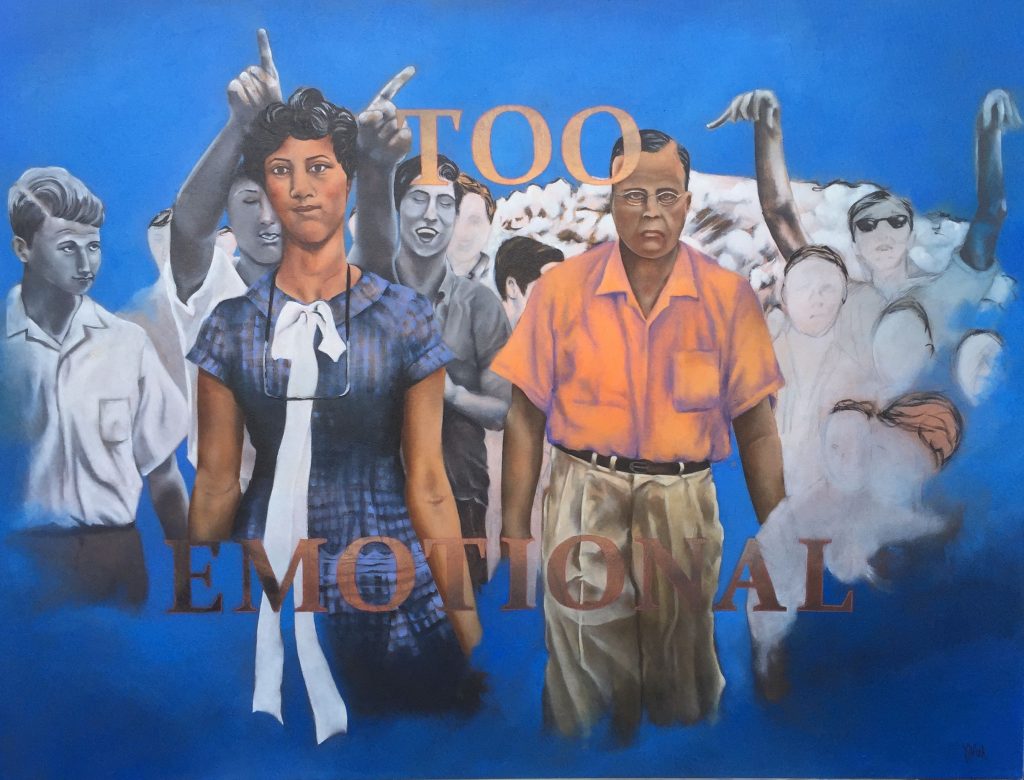

Advertising stock images, film stills, and news stories from this historical period are the compositional basis for several of Miller’s paintings. Dorothy Counts(2019), drawn from a black and white press photo, pays homage to Dorothy Counts-Scoggin, who, in 1957, suffered the harassment from the white community for being the first black student admitted to Harry Harding High School in North Carolina.

The warm tone of the underpainting shows through the homologous crowd behind Dorothy; Miller has left them unfinished. Dorothy herself steps forward as the more realized character, in full color. The painting Franca Viola(2019) similarly honors the story of the first Italian woman who, in 1966, publicly acted against traditional Sicilian social code by refusing to marry her rapist.

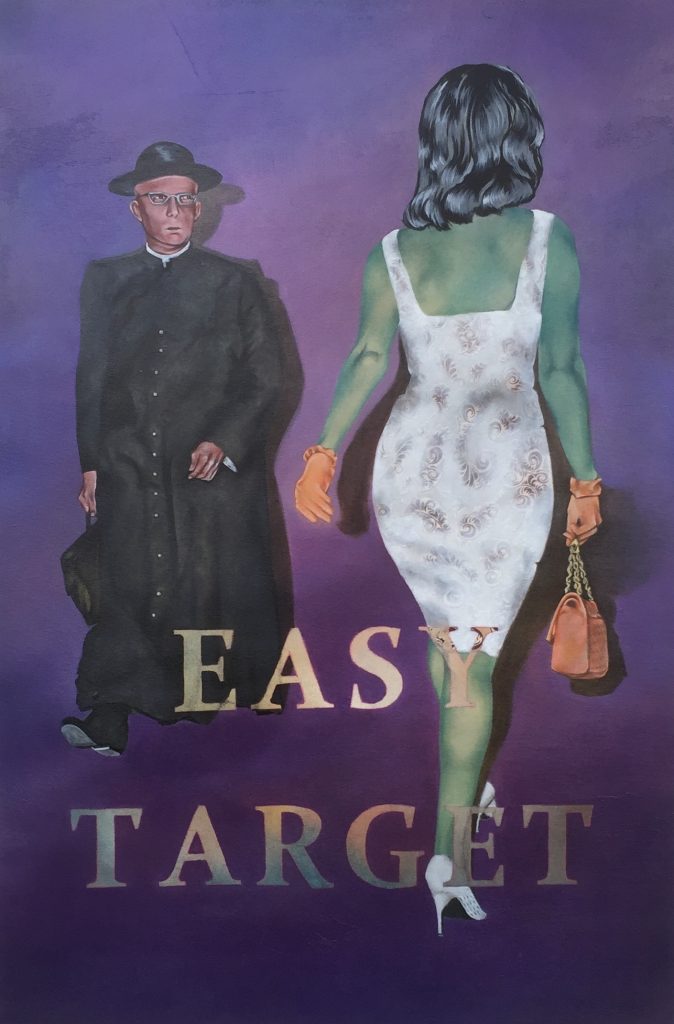

Text is paired with image in all the paintings. Provocative phrases such as “TOO EMOTIONAL” and “EASY TARGET” in large serifs float on top of the image like ad copy. In Repeat After Me (2019), the disjunction between text and image reads as sarcasm or defiance. The words “FOLLOWS ORDERS WELL” is stamped over a man wagging his finger at a woman angrily avoiding his gaze. The image is taken from an old black and white film – iconic of attitudes from the past paired with 21st-century irony.

There is a big gap of time – nearly seventy years – between the images the artists references and her individual reaction to the attitudes they embody. As Miller asks viewers to consider these biases alongside our own contemporary ones, she charts a kind of retrospective timeline. Where did our views on women’s rights come from? How does our way of thinking compare to those of previous generations? And how do these attitudes transform and persist in the unexamined corners of our own minds?

Milller’s investment in these period images – her insistence that we compare contemporary attitudes alongside those specifically from the ’50s and ’60s – belies an interesting question: once ingested, how long does the media we consume stay with us? What attitudes can we say are truly our own? The use of large text in Miller’s work may recall for viewers the work of Ed Ruscha. His Pop Art work addressed the contemporary understanding that there is no unmediated access to anything – not language, ideas, or social relationships.

Miller seems to acknowledge this in her series of paper-doll collage paintings. Within the timeline of nostalgic remanances she’s created, she inserts artifacts from her own childhood (from the ’80s). InKatie (2019), the paper doll outfits indicate the range of possible roles Miller was given for her doll. Overhead, Miller has written out more realistic stories for her dolls, freeing them from designed restrictions.

Miller’s paintings and their nostalgic fascination proves that cultural media has a latent power, one that unfolds in us over time and can’t be confronted until we’re much older – or even deferred to the next generation. Miller’s interest in the past proves that media and the attitudes they carry are not simply imposed upon us, but become internalized by society; we can learn body shame, not just from television, but from our own mothers.

Miller’s cites this struggle to decide what we truly believe in the mediated self. This is key to understanding how we might choose to realize our political ideals, as well as how we, in our personal lives, might resolve the discomforts of a disturbing lineage.

The Velvet Hammer

November 15, 2019–February 7, 2020

MonOrchid

214 E Roosevelt St, Phoenix

monorchid.com