Kehinde Wiley jokingly says it after touching one of his pieces. He seems befuddled by the irony of creating a work—only to have it policed by collectors and museums once it is sold. There’s a moment of laughter that bounces off the walls at the Phoenix Art Museum, accompanied by a release of tension, as the media, invited for press day, realizes that he is human, too.

This moment serves as a kind of template for Wiley’s work. In his own words, he seeks to mix opposing aspects that often don’t meet in the corridor where art happens. “So much of my work deals with the sacred and profane. We create this sacred space for culture. We boil down all of those things that are considered our best parts, our best merits. Then there are adults who say ‘this is acceptable’ and ‘that’s acceptable.’”

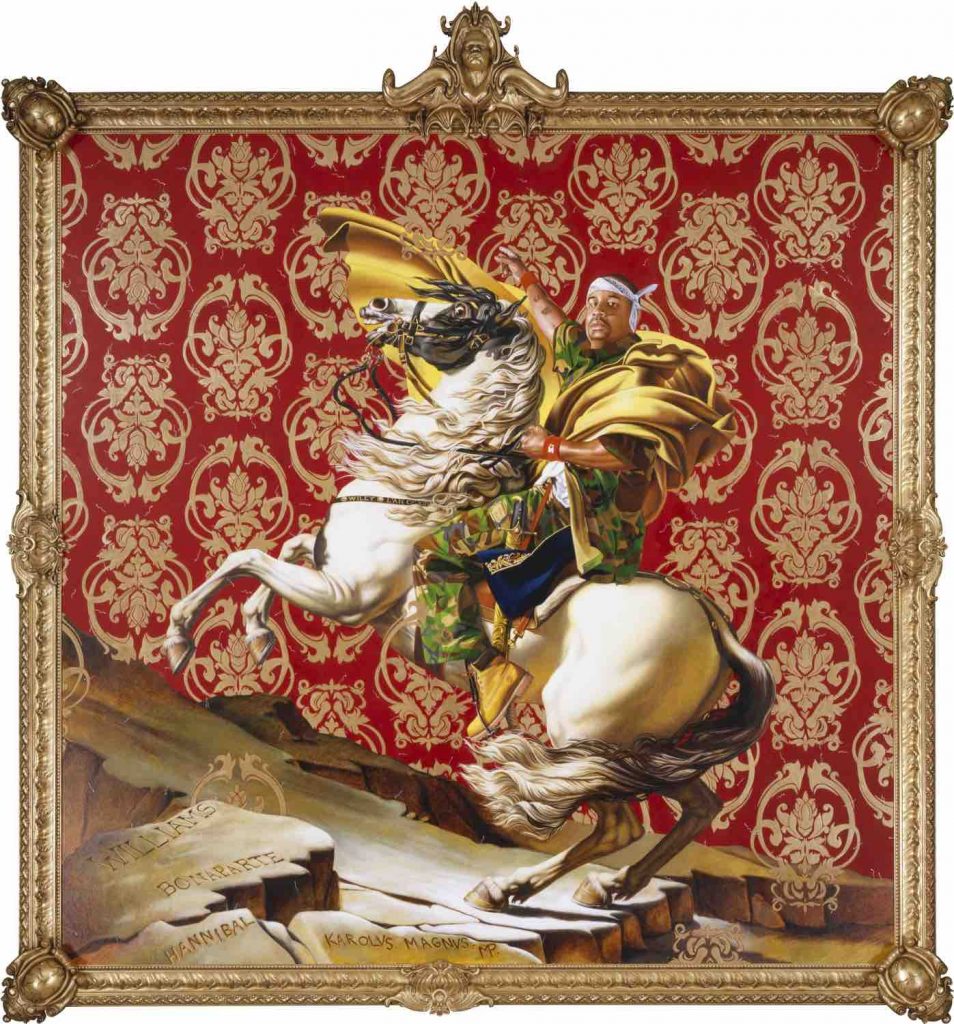

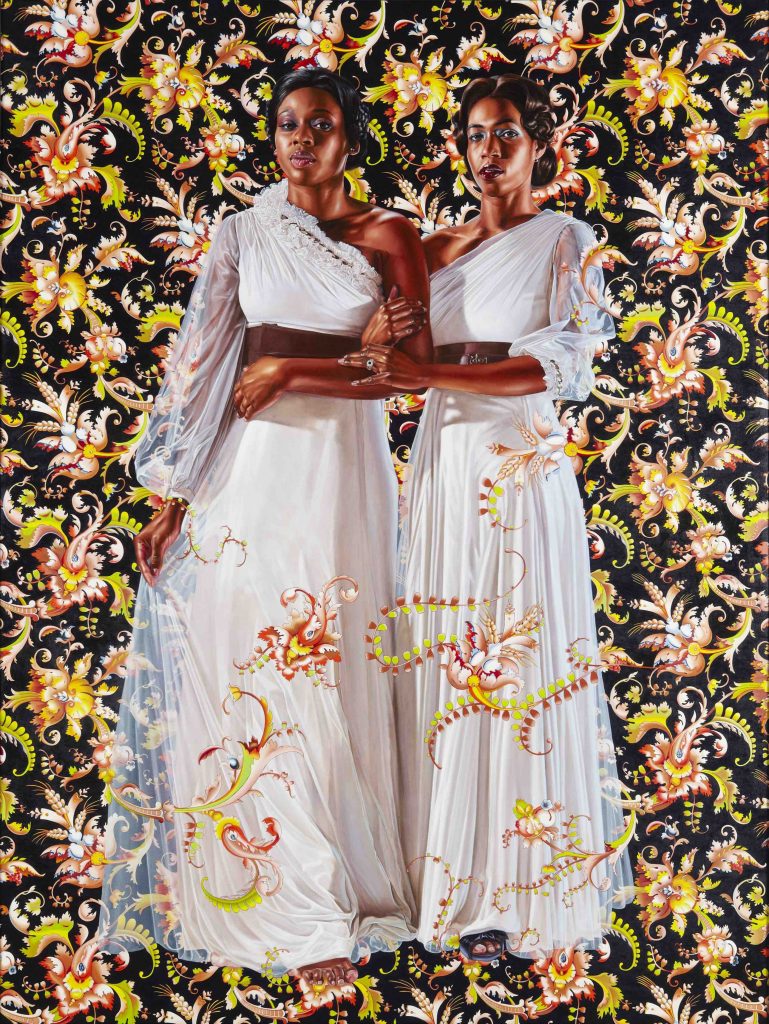

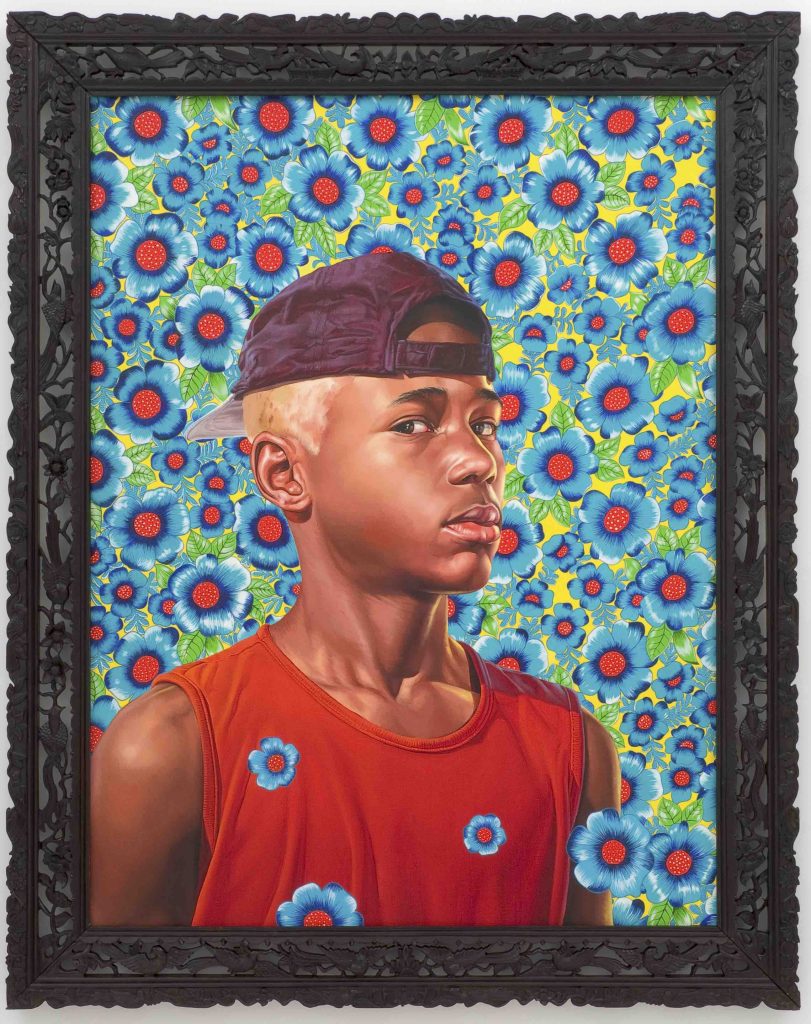

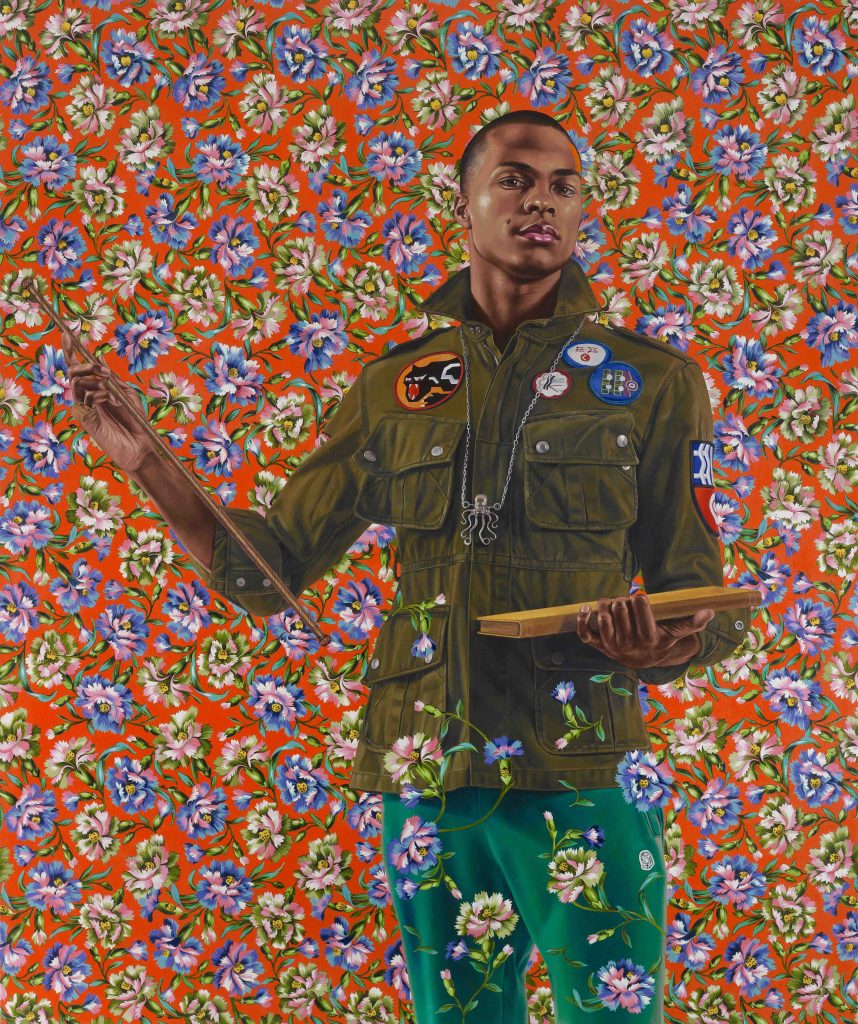

Wiley’s “A New Republic” is a traveling retrospective curated by the Brooklyn Museum. The show highlights 15 or so years of his illustrious career in art making. Wiley is best known for depicting people of color in urban attire, in imp erial poses, juxtaposed against classical art backgrounds. The art world is often testament to the best of culture—and the people who make decisions in this world aren’t often people of color. “My work does away with that system and problematizes that system,” Wiley said. “Eventually you want to see yourself in that narrative.”

In a lot of ways, Wiley doesn’t just include people of color, but he reverses the narrative itself. For many artists, brown bodies are there to serve the artist and his vision. Principal to Wiley’s work is the storytelling aspect—having people of color tell their own story, and his along the way.

The piece that Wiley touches is no accident; it is the second work he presents to us: an African American youth with his back to the viewer. Wiley references Foucault’s Panopticon, which is a tower at the center of a prison where a guard can sit and see all the prisoners without their being able to tell whether or not they are being watched. In the same way, people of color who are objectified under the gaze of art are trapped in this shadow of visibility.

Wiley’s show is an important one for the Phoenix Art Museum. In many ways, it embodies the vision of the museum’s chief curator, Gilbert Vicario, who believes that Wiley “represents our community. He represents a large segment of people in Phoenix.”

Beginnings

Wiley grew up in South Central Los Angeles with five siblings and a tireless mother—her name is Freddie Mae Wiley—who studied linguistics at UCLA. She raised the children on welfare checks and whatever spare change she could gather from her thrift shop. Wiley’s Nigerian father left him at a young age, and his mother discarded all photographs of him.

Wiley was a twin and spent a lot of his early years hanging out with his brother, who was also artistically inclined. The two of them would tinker around their mother’s shop, fixing and repurposing things. In many ways, this early childhood experience serves as the guiding movement in his work: cataloguing and refurbishing the past, playing with narratives.

Wiley’s mother recognized his artistic acumen and took him to the Huntington Library, outside Los Angeles. It was here that Wiley first encountered the lavish European portraits of colonial masters. At age 11, he began taking art classes at a state college. Around the same time, his mother sent him to Russia to study the fall of the Soviet Union in an art program.

This was the first time that Wiley left Los Angeles, and it did a lot for his growth as an individual. After going to Russia, he continued to take art classes and eventually went on to study at San Francisco Art Institute. He secured a scholarship to attend Yale in 2001, and later became an artist-in-residence in Harlem at the Studio Museum.

A Mugshot Becomes an Opportunity

Around the time Wiley was in residence at the Studio Museum, Wiley found a discarded mugshot on the street that would cause a turning point in his work. He wanted to properly combat the stereotypes that often spoke for his culture and instead present his people in a more esteemed light. Wiley began approaching people on the street and inviting them to his studio in Harlem to look through art books and find artworks that spoke to them—that somehow told their story. The subjects would then choose wardrobe items, and Wiley would shoot a photo and create a painting based on the historic piece.

To Wiley, the African American diaspora shares a lot in common with nomadic tribes. “People who have to deal with radical contingency—always on the move, always insecure. Insecurity breeds a way of thinking about the future that is radically different. That’s why jazz is about inventing a tune in real time. Nothing is written down. It’s all about call and response. It’s about how one reacts to an environment. It’s an adaptive, almost a Darwinian response,” said Wiley.

Ever seeking to expand his horizons, Wiley decided to travel the world and photograph people of color. His journey has led him to many places, including Israel and Africa. He stresses that he’s more interested in the people than the politics—especially with regard to Israel. “How does anyone walk into a conversation about Israel without being mired in the conflict?” Wiley asked. “What gives me the right to go into that place and have anything to say? I see those brown bodies and identity questions, and want to respond.” Portraits from around the world were put together in Wiley’s popular “World Stage” exhibition.

For Wiley, one of the most interesting aspects of his travels was seeing how hip hop has been projected throughout the world. “The leading edge of American imperialism is hip hop,” said Wiley. “We beam it out all over the world, and young people pick it up. They fashion themselves and figure out their revolution stories. It’s not surprising that hip hop is the great unifier—it’s free radical expression,” Wiley said.

A New Republic: A Retrospective

One of the most iconic pieces in “A New Republic,” and the only commission on display, is of the late Michael Jackson on horseback. The piece is more than 10 feet tall and occupies its own wall in the museum. It’s not surprising that this is the first piece in the exhibition and one of Wiley’s most recognized worldwide. It was featured on the Fox television show “Empire,” and in many ways Wiley is building his own empire. He is inspiring other artists to tell their own stories, rather than having stories told to them.

It must be noted, however, that a lot of the storytelling that Wiley engages in borders on self-portraiture in some way—the telling of his own story. At a young age, he would engage in actual self-portraiture, but he says it felt embarrassing to render himself, Michael Jackson-esque, in costumes. However, he was engaging in the play of colonial power he saw festooned in classical art depictions. “It sounds silly, but that was the propaganda of the day. That was the convincing apparatus at the time. I think it’s much more important to recognize that this entire project is a self-portrait,” Wiley said.

“There’s a queer aesthetic, an American-ness and a black-American sensibility to it. As we get closer and closer to this thing, we are arriving at me. It’s important that it broadens from the United States, because it approximates an even more accurate depiction of the source. In the end, you stand on the shoulders of so many people who come before you. You’d be a fool to think that it’s about you. All we are doing is fighting against mortality,” Wiley said.

Kehinde Wiley

“A New Republic”

Through January 8, 2017

Marley Gallery

Phoenix Art Museum

phxart.org

Images:

Kehinde Wiley portrait: Photo by Tony Blair

Kehinde Wiley, Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps, 2005. Oil on canvas. Brooklyn Museum, Partial gift of Suzi and Andrew Booke Cohen in memory of Ilene R. Booke and in honor of Arnold L. Lehman, Mary Smith Dorward Fund, and William K. Jacobs, Jr. Fund. © Kehinde Wiley. Photo: Sarah DeSantis, Brooklyn Museum.

Kehinde Wiley, The Two Sisters, 2012. Oil on linen. Collection of Pamela K. and William A. Royall, Jr. Courtesy of Sean Kelly, New York. © Kehinde Wiley. Photo: Jason Wyche, courtesy of Sean Kelly, New York.

Kehinde Wiley, Houdon Paul-Louis, 2011. Bronze with polished stone base. Brooklyn Museum, Frank L. Babbott Fund and A. Augustus Healy Fund. Photo: Sarah DeSantis, Brooklyn Museum.

Kehinde Wiley, Randerson Romualdo Cordeiro, 2008. Oil on canvas. Private collection, Golden Beach, Florida, courtesy of Roberts & Tilton, Culver City, California. © Kehinde Wiley. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer, courtesy of Roberts & Tilton.

Kehinde Wiley, Anthony of Padua, 2013. Oil on canvas. Seattle Art Museum; gift of the Contemporary Collectors Forum. © Kehinde Wiley. Photo: Max Yawney, courtesy of Roberts & Tilton, Culver City, California.