Candice Breitz, Stills from “Love Story,” 2016, Featuring Julianne Moore and Alec Baldwin

Top: Shabeena Francis Saveri, Sarah Ezzat Mardini, Mamy Maloba Langa / Bottom: José Maria, João, Farah Abdi Mohamed, Luis Ernesto Nava Molero., 7-Channel Installation

Commissioned by the National Gallery of Victoria, Outset Germany + Medienboard Berlin, Brandenburg, Courtesy: Goodman Gallery, Kaufmann Repetto + KOW

To mark its 20th anniversary and commemorate its movie theater past, Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art presents an exhibition entirely focused on the moving image. “Now Playing: Video 1999–2019” brings together works by 11 international artists and samples both major contributions to video art and works from SMoCA’s collection. The exhibition highlights different aspects of video: its ephemerality, animation, and its relationship to narrative.

Writing on the relationship between painting and cinema in 1967, French film theorist André Bazin distinguished the space of the picture frame from that of the screen. A painting, Bazin wrote, pulls our gaze inward, but the screen harnesses a centrifugal force that propels us outward. The moving image, unlike its still counterpart, exists in time, and in many cases blurs the line between reality and fiction.

This exhibition poses an intriguing situation in which to view video. Instead of solely being secluded in darkened, soundproofed rooms or confined to a monitor via headset, the exhibition allows for sets of relationships and rhythms to take form. In one gallery, the metronomic sound of dribbling a basketball from a video by Mark Bradford bounces through the space, becoming an acoustic aspect of other works in the room.

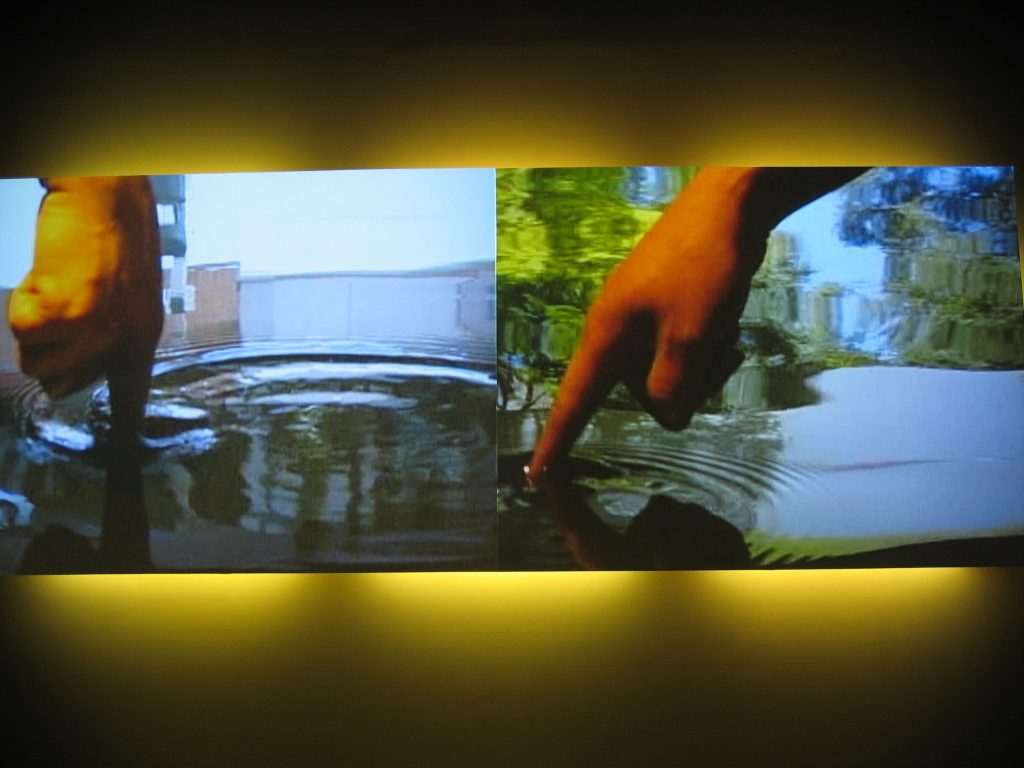

Song Dong (b. 1966, Beijing, China, where he lives and works), “Floating: Scottsdale,” 2005

Video projection, Duration: Left screen 21:38, right 17:16, Collection of Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Purchased with funds from Mai Yahn, Richard Hayslip and Sara and David, Lieberman

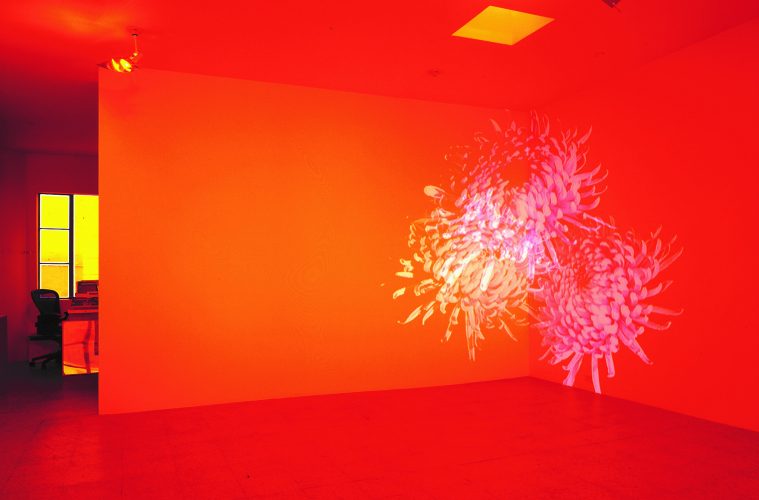

The experiential light and projection works by Diana Thater and Aaron Rothman complement one another. Both artists are concerned with the natural landscape. Thater’s Orange Room Wallflowers contrasts nature and beauty with technology and artifice. Rothman’s slow-moving simulation of light moving across the wall plays with the viewer’s sense of orientation. Looking up toward the ceiling, you try to discern its cause – the skylight or the projector?

Shirin Nest’s Turbulent is in the next space over. Prior to seeing this installation at SMoCA, I had only seen poor reproductions of it on YouTube. It’s mesmerizing to see and hear. Upon walking in, the viewer is caught between two black-and-white videos that stand in for two opposing forces. In one, a man performs a traditional song in front of a full audience of other men; in the other, a female singer, Sussan Deyhim, delivers an ecstatic and deeply moving vocal performance with no audience. For Neshat, this duel of opposites highlights the inherent social and political gap between genders in Islamic Iran.

A second gallery contains a total of eight looping videos by four different artists, all of which clock in at under four minutes. The display of these is reminiscent of that of painting, in that the moving images exist on a picture plane and in relation to one another. One can quickly hop from one to the next or devote a few minutes to each. These images, unlike painting, seem to morph in time endlessly.

The animations on view by Christian Marclay provide one such example. At first, each work seems to be a catalog of images: chewing gum, bottle caps, cigarette butts. Minutes in, the images start to transform into playful flipbook narratives. The blotches of chewing gum on the sidewalk split and multiply like a culture of microscopic cells. The bottle caps of different colors and brands seem to remain still on an ever-changing ground. The cigarette butt slowly inches back up to completion, only to dwindle down again.

Simpson Verdict, a short animated video by Kota Ezawa, is based on footage from the O.J. Simpson trial. The audio of the verdict, playing from a speaker above, is stark against the cartoonish and flattened image of Simpson’s response to the verdict. The trial was a media event – even if you didn’t particularly follow it, you knew about it. The video speaks to the way reality is rendered and compressed by popular culture.

Kota Ezawa, “The Simpson Verdict” (still), 2002; Courtesy of the artist and Haines Gallery, San Francisco

Candice Breitz’s large-scale video installation in the next room, Love Story, similarly approaches media imagery. The setup itself is like a movie theater. In separate clips, Alec Baldwin and Julianne Moore appear on set in front of a green screen, each telling tidbits of an emotional tale of escape. Almost immediately, we know they are acting, but the question is: As who? Behind this Hollywood rendition is another set of six screens and narrators who are refugees, but here they are telling their own unedited stories. Only when the curtain is pulled back completely do we have the opportunity to truly empathize.

“Now Playing: Video 1999–2019”

Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art

Through May 12

smoca.org