Even the name has a haiku quality to it—an ancient mystique that dances around the word. A collotype is high-quality print made by exposing light-sensitive gelatin to create an image without using a screen. These prints have an unforced, aged feel to them, transporting the viewer to another time with their antiquated tones. The collotype served as a precursor to lithography, which eventually proved more cost effective. Now, the collotype process is used primarily for fine art, and for Phoenix printmaker Jacob Meders, it is a vehicle for reconfiguring history.

One of the foundational dialectics underscoring most of Meders’ work is the question of reclamation. Meders is a member of the Mechoopda Indian Tribe of Chico Rancheria, California, and his work wrestles with preconceived notions of Native identity and history. In that sense, working with collotype and printmaking in general allows Meders to edit the past and offer alternative perspectives of his people. Collotypes also serve as metaphors: they employ the past to speak to the future.

Mirrors Reflecting Mirrors

For Jacob Meders, art should open further dialogue and create questions. “Some of the best work I’ve seen is not an answer or a solution to something. Usually it’s a really good question that one could spend a lifetime dancing around, filtering and diluting.”

Meders created work that reinforces this notion while studying at the Savannah College of Art and Design. He took those old, distinctive Mexican blankets and painted on top of them images associated with Native culture, including woven baskets, with a contemporary twist. Meders became fascinated with the idea of altering the Mexican identity represented by the blankets. Blankets also have a specific historical significance for Native Americans. They were used for comfort, gifts, ceremonies and, by enemies, to spread disease (smallpox).

This project represents Meders’ vision of reclamation. “In some way, I was masking the identity of Mexico,” said Meders, “[by] re-layering a new identity on an old blanket. There are so many indigenous people in Mexico, and we look at them as ‘Mexican’ because they speak Spanish. But a lot of these people are actually mestizo—mixed culture. Many of them have been told that they are of Spanish origin and identify with that.”

The blanket pieces serve to help answer questions that Meders continues to come back to: How do you make something new out of the old and preconceived? How do you create a new idea in the shell of history, antiquity and prejudice? These ideas continue to expand as Meders advances as an artist. “The more that you grow and the world grows around you, the more that it [your dialogue] grows richer and richer,” said Meders.

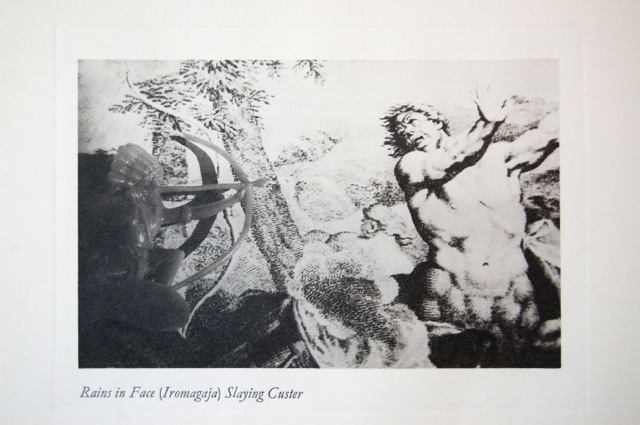

Too Many Capitalists, Not Enough Indians

The printing and dissemination of images was the primary means by which Native Americans came to be seen as heathens and savages. “When I learned the history of print and how it applies to Native identity, I was like ‘Wow, here’s a well so deep that I can dig forever.’ In Europe, some of the first prints showing Natives depicted them as cannibals running around naked—completely uncivilized—as if they needed to be controlled and guided. It was a way of justifying a policy of manifest destiny,” said Meders.

Given this history, Meders tries to utilize printmaking, the old tool of prejudice, for good. “I’ll use it as a weapon to rebalance the Force, in a way. There are those collectors who try to possess the ‘Indian,’ and I try to mock that. Their collections don’t affect me because I am doing something completely different. I contradict that stuff. I like to use Western aesthetics and processes because they’re familiar to non-Native people.” Meders essentially uses Western, linear language to tell the multifaceted history of Native people in images that are authentic.

One of his prints, entitled “Kill the Capitalist, Save the Indian,” takes the old phrase “Save the Man, Kill the Indian” and remixes it. He created the piece through his printmaking company, Warbird Press, which is located at The Hive in central Phoenix. Meders started Warbird about five years ago, just after he graduated from Arizona State University with an MFA in printmaking. It is an indigenous-minded press that works primarily with Native artists, but has also collaborated with non-Natives.

High School Underachiever, Dean’s List Bachelor

Meders graduated from high school in Florida with a 1.5 GPA. School was something that got in the way for him. He had to work in order to help his mother—who was separated from his father—and he liked to surf. From early on, he gravitated toward art. A lot of people in his family were artists, as well. Prior to entering high school, Meders just figured that everyone was into art because of the ubiquity of it while he was growing up. After barely earning his high school diploma, Meders was determined to get into an art program. The Savannah College of Art and Design accepted him, based on his portfolio, with one condition: that he starts the program on academic probation. Not only did he met the demands of probation, but he made the dean’s list. Going to art school connected him with his passion for creating.

Besides his professors, another Native artist, Zig Jackson, especially inspired Meders. Jackson served as a mentor, and at one point he asked Meders to trade pieces. This was a pivotal moment for Meders. For a while, he had struggled with the notion of identifying as Native. “It [identity] is a real sticky situation, because there’s a part of me that has no problem talking about issues relating to my culture and putting that in my work, ’cause that’s a part of my history and I want honor that,” Meders said. “[However], I feel like people tend to label Native artists. We get thrown into certain boxes, and only selected for particular exhibitions. There are a lot of expectations that come with this label.” When Jackson took Meders under his wing, it gave him the courage to step out and embrace his identity.

Before graduating, Meders exhibited his work in the school’s anthropology museum. “I told them that, in a lot of ways, I’m questioning the authority of the institution, and anthropology is part of that equation. There’s a big stain on history through the anthropology of Native people,” said Meders.

After graduating, he went on to attend ASU’s MFA program, where he was paired with many skilled printmakers, but none of them were Native. This was a bit of a concern at first. However, Meders decided to stick with ASU because of the vibrant Native American culture in Arizona. Meders names a few people that were especially helpful in his development as an artist: Steve Yazzie, Kade Twist and Andrea Hanley.

Printmaking helps Meders remix the past—and honor both the past and future. He has achieved wide success as an artist, producing work that challenges how we perceive the conflation of identity in art. His work has appeared in galleries and museums around the world, including the Heard Museum.

Moving Forward, Giving Back

Meders takes trips back to visit his tribe in California about twice a year. He sees himself and his generation as necessary for preserving the stories of their elders. He goes up, listens and helps when he can. He does printmaking workshops with the kids. They make bird books in their native language that pay homage to the old stories. They also create personalized t-shirts. Meders knows how these kids struggle with identity and belonging.

Meders also teaches studio art at ASU West. There is a give and take that is evident in his life and work. He feels compelled to teach, to listen and to usher in the future through the hallowed doors of the past. He might not find answers in art, but that’s not a problem, since he is definitively questioning the very notions that uphold our lives and the lies we fall into.

jacobmeders.com