South Phoenix has been forgotten by the city. It is isolated and contained, pushed back against the South Mountain Preserve and bordered to the north by the Rio Salado—two geographic features that define its edges, framing the empty lots and dilapidated buildings between.

Traveling up the Central Avenue corridor, narrow streets and blighted shops give way to high-rises, new development and a downtown revitalization, which has spread into the Warehouse District, a little further to the south. With the extension of the light rail to South Phoenix, scheduled to open in 2023, this inequality may all soon change.

The disparity between the two sides of the Rio Salado is not an accident. A legacy of segregation and displacement hovers over the area, leaving a distinct mark that separates it culturally and economically. Cuatros Milpas, Golden Gate and other barrios that existed across the railroad tracks have either vanished or continue to dwindle, their names unknown to outsiders.

In the 1930s, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) encouraged lending to “pre-approved” areas of the city based on racially coded maps. Created from the New Deal, in response to the Great Depression, these maps determined where programs and public projects would be focused in cities across the country.

In Phoenix, not only were minorities ineligible for FHA housing to the north of downtown, but local bank and federal loan programs were denied to residents south of Van Buren—a practice known as redlining. Cut off from the financial services available in the white neighborhoods uptown, South Phoenix’s growth was hindered, while its people continued to live in substandard conditions.

This created the blight that gave justification for tearing down several South Phoenix neighborhoods, which culminated in the 1970s and ’80s when thousands of families were displaced by the expansion of Phoenix Sky Harbor Airport. Pollution and environmental degradation from Sky Harbor had depreciated already low property values, and forced sales through eminent domain gave residents very little opportunity for pushback.

The entire Golden Gate Barrio, bordered by Buckeye Road, 16th Street, Grant Street and Sky Harbor Circle, was razed, with the exception of one structure—the iconic Church of the Sacred Heart. An island in an urban desert of dirt lots, the church was eventually added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2012. Since 1986, its doors have opened once a year to former neighborhood residents, for Christmas Mass.

With the expansion of the light rail come new opportunities, mobility and investment—but also skepticism. Once again, a major development will change the social and urban fabric of neighborhoods that have persevered through nearly a century of policy aimed against them. The new rail line down Central Avenue from Washington to Baseline Road won’t be completed for another six years, but already the community is working to make sure their voices are heard at every step in the process.

———————————

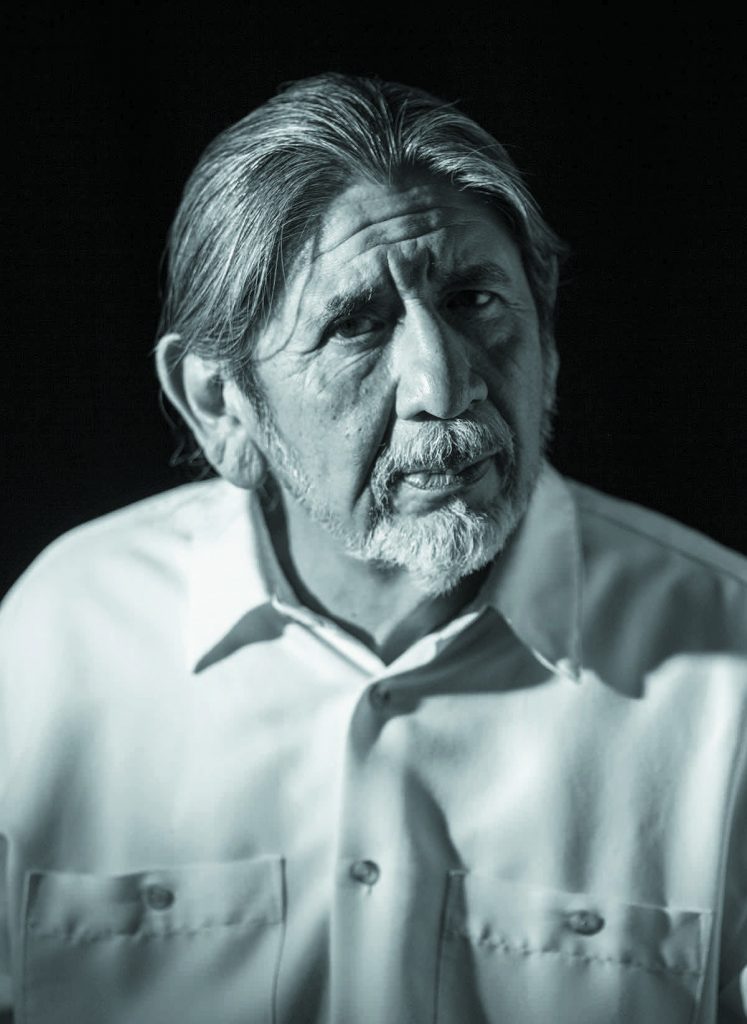

Martín Moreno has been a resident of South Phoenix for over 35 years. He arrived here from Tucson and began working as a muralist in the neighborhoods, and also as an educator. Moreno, however, prefers the term “cultural warrior.”

Photo: Daniel Swadener

He is one of the many artists selected to provide public art works for the new five-mile extension, which will adorn light rail platforms and stand along the route. Of the 14 artists awarded contracts, 10 are from the Phoenix Metro area, and many of those are from South Phoenix.

This is an example of how the project, now only in the planning phase, has already brought opportunity to the area. But as Moreno explains, it wasn’t that simple. “The fact that 10 local artists, many of whom are from South Phoenix, were awarded contracts is not just coincidental. That was due to a lot of hard work, and the selection process was evened out so that we would be represented properly,” Moreno explains.

The hard work entailed community workshops and meetings to help artists submit their proposals and navigate the grant-writing process, which can be long, laborious and daunting without the proper resources.

“There are a lot of artists from South Phoenix, many who graduated from South Mountain High School. I mentored many of those artists, and they need a place to work where they can develop their skills and show their work,” Moreno says.

The Sagrado Galleria, which Sam Gomez and Jay “Tranzo” Olivas relocated to South Phoenix in 2016, is just that kind of place. Since opening on Central Avenue along the light rail’s eventual route, the Sagrado has served as a hub for community participation, especially for those concerned with making sure South Phoenix has a voice in the rail extension. “It was at Sagrado Gallery where we met as artists and as community members. I give credit to [Gomez] and his contacts who ensured that this whole process went down properly,” Moreno says.

Francisco Garcia, a muralist who moved from Los Angeles to South Phoenix in 2003, says artists from the south side have faced difficulties that others have not. Their art is often relegated to their side of town and not represented in galleries throughout the city. “There are people that have been involved in the public arts [in South Phoenix] for over thirty, forty years—longer than some of the younger generation have been around. Their experience, and our experience in the community, hasn’t always been an easy one. There have been a lot of times when artists don’t get paid or they’re not getting the same opportunities,” Garcia says.

Gomez cites the light rail plans and gentrification within the Roosevelt Row arts district as motivation for relocating the Sagrado. With a downtown that is becoming increasingly expensive, artists are in need of new spaces. Where they will go is anyone’s guess—the Grand Avenue arts district and 16th Street north of McDowell have served as alternatives, but South Phoenix is home to a large group of the artists that populate the city, and their growing presence is being felt.

Photo: Jeremie Franko

For people like Moreno and Gomez, the changes happening south of the Rio Salado are the result of dedication to a place they call home, rather than just an exodus from the city’s established arts district in search of cheaper rent.

———————————

With new investment comes risk. The opportunities the light rail will bring to South Phoenix are counterbalanced by the same factors that gentrified Roosevelt Row. Luxury condos and development will creep their way south of the railroad tracks, where the trauma of displacement and segregation committed in the name of progress already looms large.

“Any metropolis has that history,” Moreno considers. “Phoenix has it in the expansion of the airport. All those neighborhoods were either relocated or disappeared from the face of the earth. All that history and culture were erased, and there was a lot of resentment towards the city because of it.”

He continues, “I’m sure that will be the case with the light rail extension, unless people like [Gomez] and other folks who are invested in South Phoenix maintain its character and ensure that dislocation from identity doesn’t happen.”

This does not mean that development isn’t welcome. South Phoenix fought for the light rail to come, and now it will fight to make sure its residents receive the economic benefits it brings. “That boils down to community participation, community organization and trying to hold the city accountable for anything—including negative things that may come from the light rail,” Moreno reasons.

Photo: Sam Gomez

When viewed through the lens of history, the light rail’s extension may continue the legacy of displacement. Time will tell how and to what degree the residents benefit. Homes and businesses along the path will certainly be affected as the city is irreversibly changed. This is true of any major urban development, but the negative impacts sting that much more where former barrios were once located, their names now forgotten, or never learned, by those north of the Rio Salado.