Yosemite Valley is often noted as one of California’s, and perhaps North America’s, most important and iconic ecosystems. Home to black-tailed deer, bobcats, and the American Black Bear, as well as dozens of species of birds and butterflies, its sun-showered plains and sheer granite rock faces inspire awe in the hearts of millions of visitors each year.

But some of the most well-known humans to leave their mark, metaphorically and historically speaking, are the indigenous people of Yosemite Valley and the generations of later artists who were moved to try to capture the essence of this sacred and timeless place.

At the crux of the modern and ancient are the new human interventions that began to take place in Yosemite in the early 20th century when it was designated a national park. Now on view at Heard Museum are three sets of work set in Yosemite and created by British-born artist David Hockney, which provide a modern, almost Technicolor backdrop to the 28 pristine handwoven baskets made by Mono Lake Paiute and Miwok women in the 1920s showing in David Hockney’s Yosemite and the Masters of California Basketry.

“When the first explorers went to Yosemite, they talked about it as this vast wilderness, which was not the case,” says curator Erin Joyce. “Yosemite was a garden. These indigenous communities – the Miwok, the Mono Lake Paiute – tended to it. They cared for this landscape. Part of the reason was to have food and have materials for these baskets that you see on display. So it wasn’t this untapped, untouched wilderness that was propagated by settlers. It was a home; it was a garden.”

Encompassing some 1,200 square miles of wilderness, Yosemite was officially designated a national park in 1906. Conservationist and explorer John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club, had been writing about the place’s pristine beauty for decades. In 1903, he hosted President Theodore Roosevelt on a four-day camping trip through some of California’s most rugged lands. The journey sparked intrigue in the president’s mind, and he agreed to help protect the land.

However, the federal designation of the place as a national park meant a change in legal status for thousands of its native inhabitants. According to Joyce, parks personnel, “sort of as a marketing device, as a way to draw local tourism from neighboring cities like Sacramento or San Francisco, created what was known as the Yosemite Indian Field Days. They happened from 1916 to 1926 and again in 1929.”

The events included rodeos, cradleboard judging contests, a festive atmosphere of pageantry, and a basket-weaving contest. For the indigenous people, “There were now new terms of engagement for how they could be in their native homeland,” Joyce says. “A sort of condition to being there was participation in these field days.”

The field days provided a way to showcase the works of native artists and created a new way for the native community to stay connected to the lands of Yosemite. “Yosemite is associated with some of the most important, major baskets ever produced. It’s just the pinnacle of an artform,” co-curator Ann Marshall says. “The weavers who produced them were making art, very definitely. You don’t see that in the work of their predecessors, in earlier baskets that had a more utilitarian purpose, or even a more decorative purpose.”

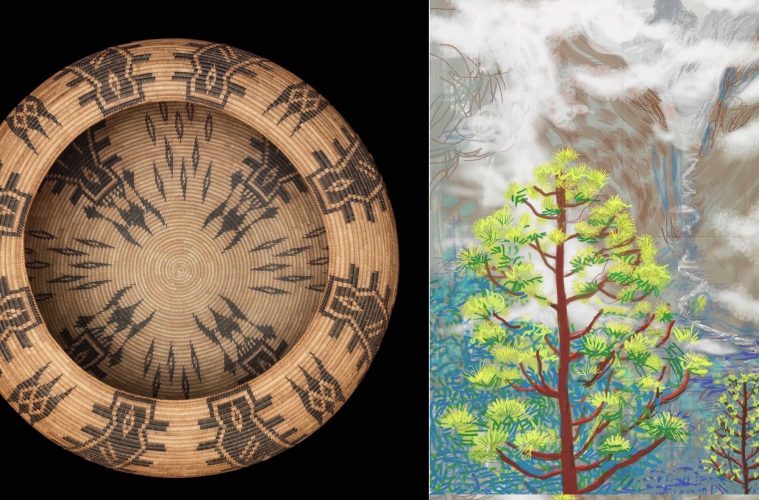

The finely woven baskets, made of dyed bracken root, redbud shoots, sedge root, and willow shoots, were produced for Yosemite’s Field Days, says Marshall, curator and director of research at Heard.

“The baskets were not created for ceremonial purposes, and they were not created for utility. They were art objects,” says Joyce.

In earlier days, baskets might be used for collecting food or other materials, or for cooking. The Miwok, for example, would cook acorn mush by dropping the mashed raw food and hot rocks into the basket, and then removing and replacing the rocks as they cooled. The baskets were so tightly woven, they were waterproof. The Miwok also wove fish traps, quail traps, and even scoops for harvesting seeds, Marshall explains.

“It’s also kind of wonderful that the people who collected these baskets understood their art and kept track of who created them,” Marshall says. She explains that the names of the makers represent important information. Basketmaking was largely an anonymous artform in generations past. You can’t sign a basket, after all, Marshall points out.

During field days, competitions would be held in basketmaking for accuracy, complexity, and overall beauty of the design. Designs often featured quail plume shapes, arrows, lightning bolts, and more. Highlighted basket makers include Carrie Bethel, Tina Charlie, and Lucy Telles. Nine different women artists are featured in the Yosemite exhibit. “The level of skill and the level of innovation is really spectacular,” Marshall says.

But not to be overlooked is the impressive accompanying show, Masters of California Basketry, which includes even more elaborately crafted and unique selections, highlighting the variety and versatility of baskets in shape (some are rectangular), size, style, and pattern.

All of the 28 baskets are on loan from the Yosemite Museum, inside Yosemite National Park. “It’s also interesting to look at these baskets as technology. So you have a basket that had a utilitarian purpose or a ceremonial purpose, and that technology of basketry is being adapted into this very high artform,” Joyce says.

David Hockney is a British transplant to California whose pop art images have come to symbolize the lavishness and sometimes kitsch of Hollywood. He lived on and off in L.A. since 1964 and settled there permanently in 2013.

While most modern art followers would recognize Hockney from his bright, vivid poolside scenes replete with electric green palm trees and bikini-clad beautiful people, there’s more to Hockney than sun-bleached scenes and portraits of art aficionados; the 81-year-old artist is also in touch with nature.

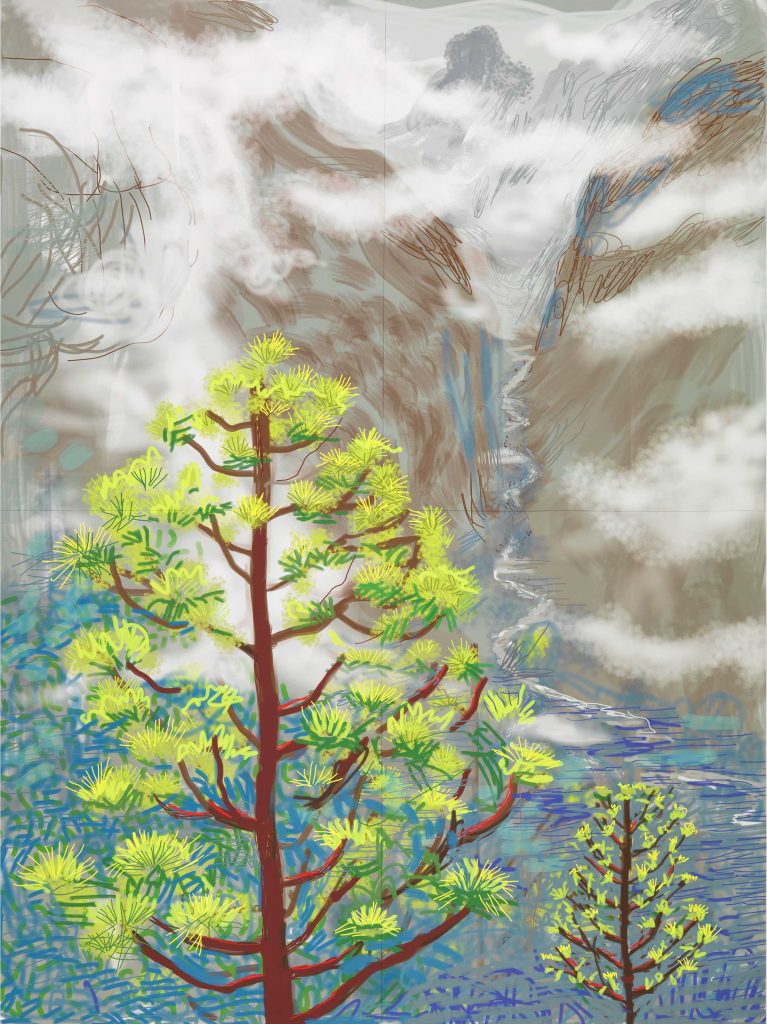

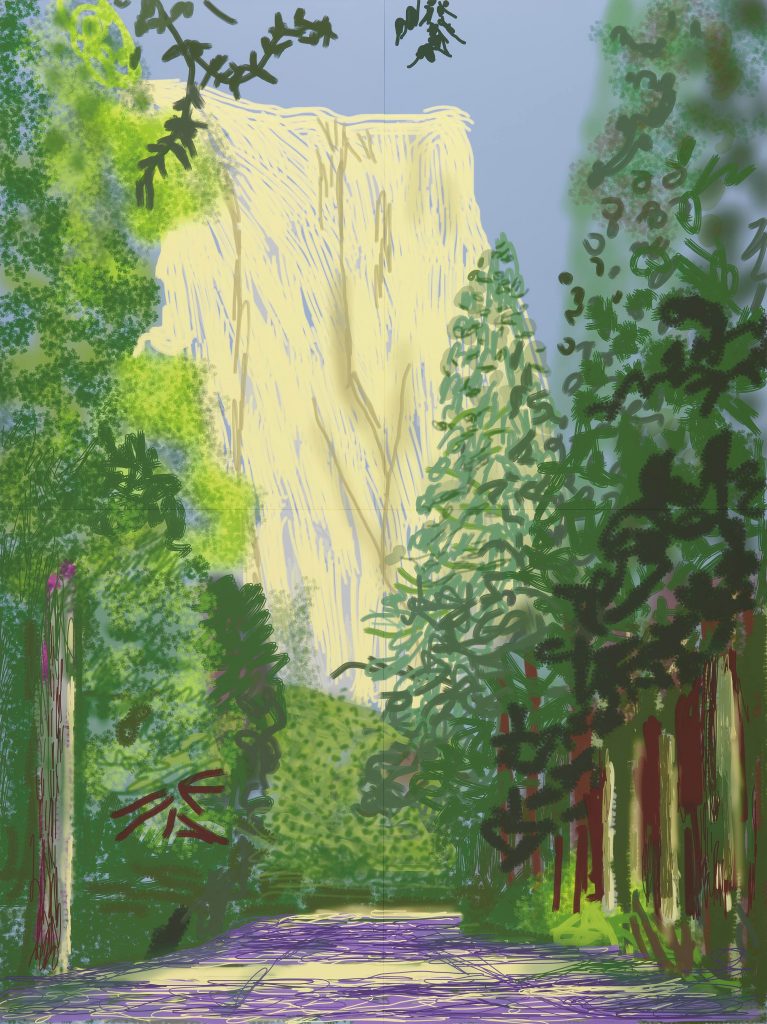

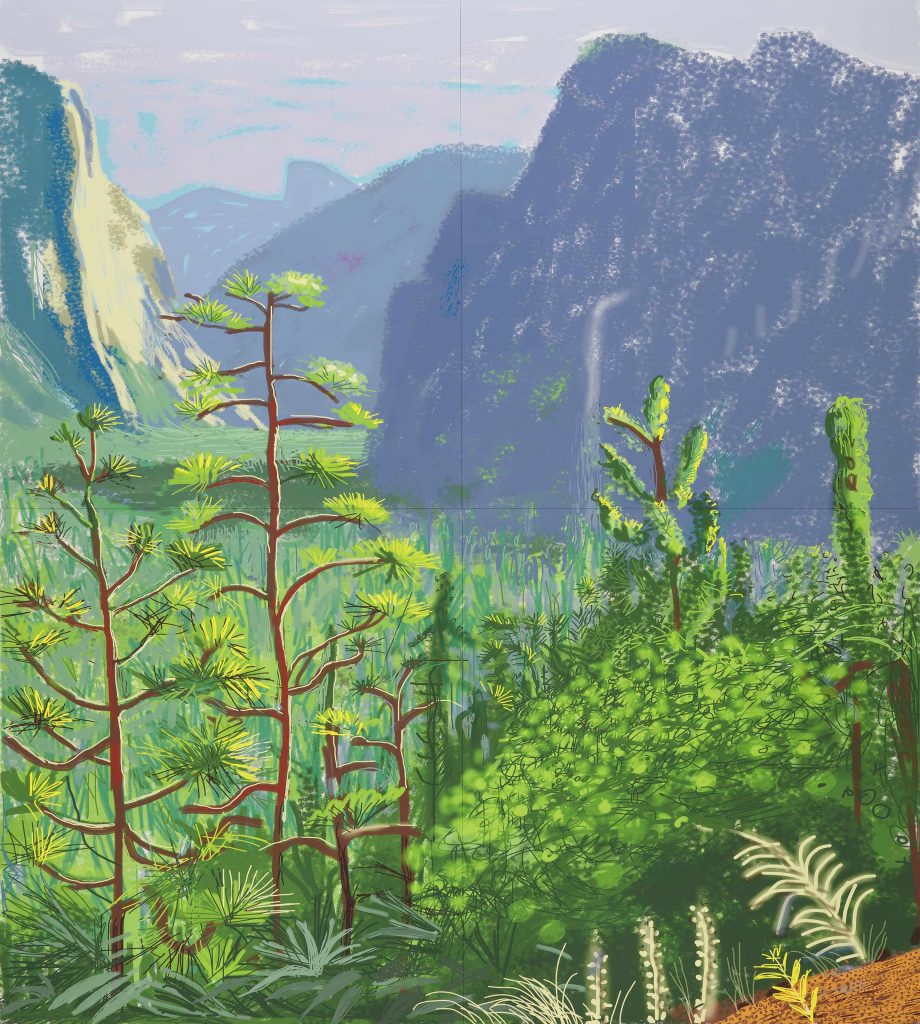

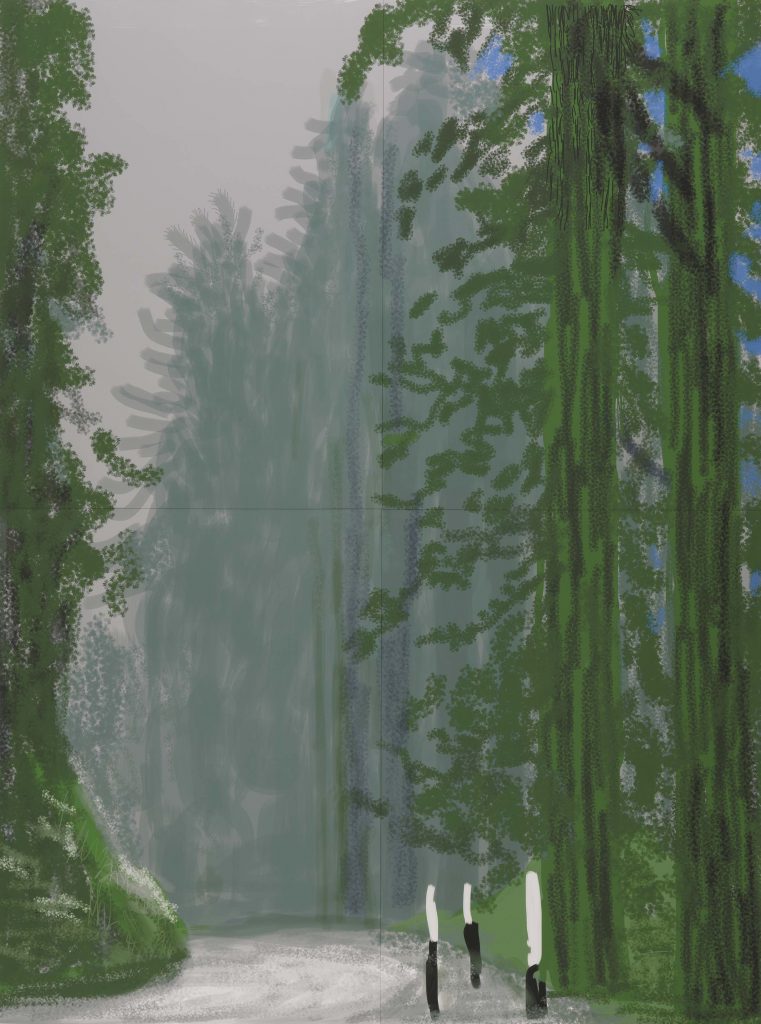

Joyce took the lead in rounding up Hockney’s Yosemite-inspired works, on loan from dozens of private collections for this show. The exhibition includes Hockney’s 1982 photographic collage series from the park, a set of 2010 iPad drawings, and a set of larger iPad drawings from 2011, Joyce says. “He’s always been an artist who has pushed the limits of mediums and explored new mediums,” she says.

After a period of documenting his daily life with Polaroids in the 1970s, the artist moved on to create photographic composites – grid-like collages pasted together from many images, shot in succession, of the same subject. Hockney called these early grid-based pieces “joiners.”

“Hockney goes to Yosemite in the autumn of 1982 with his Pentax 35-millimeter camera, and this is the very first photographic collage he ever made with a non-Polaroid camera,” Joyce says, pointing to a collage that unravels a view of Yosemite, almost as if it were a foldout tourist map. Some edges are layered, some stacked with corners overlapping. The path of what was shot does its own framing and cropping to reveal, like a keyhole, a selected focal point.

But Hockney never fully trusted nor committed to the use of photography as his primary medium. He is on record stating that photography as an artform “will never equal painting,” noting that some of its limitations are that it is “only good for mechanical representation,” and by its literal nature, cannot truly “show time.”

“The images that you see here led to him doing things with Xerox machines and photocopiers. And then you sort of flash forward to 2009, when the iPad came out,” Joyce says. The artist has always kept an open mind when it comes to experimenting with new mediums, and he soon moved into creating artworks by using digital tools. In addition to the photographic collages, two other sets of work by the artist were produced on more recent visits to Yosemite National Park (within the last decade).

Hockney was given an iPad in 2009 and took it with him in 2010. He had experience with plein air painting and drawing, but the portable iPad as a tool allowed him more flexibility and mobility. Hockney then returned in 2011 to try another series, because he wished to capture images from the park in more detail. For this second iPad collection, he adopted the use of a stylus for finer lines and also began experimenting with filters, such as stardust and spraypaint.

Bright Technicolor renditions of mountain hemlock, red fir, Western white pine trees, and other flora seem to grow into three-dimensional life from the walls of the gallery encircling the baskets. The digital drawings and their fiery color provide a lively contrast to the earth tones of the native women’s baskets, helping to connect the intergenerational intrigue of those early gardeners who called Yosemite home with the modern-day tourists who pass through and collect photographs.

David Hockney’s Yosemite and the Masters of California Basketry will be on view at Heard Museum through April 2020.