“If I ever had a mistress, it would be the Grand Canyon,” Barry Goldwater once said.

The five-time U.S. Senator wasn’t one to mince words – Goldwater’s legendary lack of filter was one of the factors that torpedoed his candidacy during the 1964 presidential election. For all his strengths and weaknesses, Barry M. Goldwater was someone who meant what he said.

But if you want to see tangible evidence of Goldwater’s lifelong infatuation with his home state, look no further than Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West (SMoW). The Old Town institution is displaying an exhibition called Photographs by Barry M. Goldwater: The Arizona Highways Collection. It’s the museum’s first-ever photography exhibition. Covering two walls adjacent to the museum’s gift shop, the Goldwater exhibition showcases photographic prints (mostly black-and-whites, with a few color shots) that the presidential hopeful took of Native Americans and natural vistas across the Southwest.

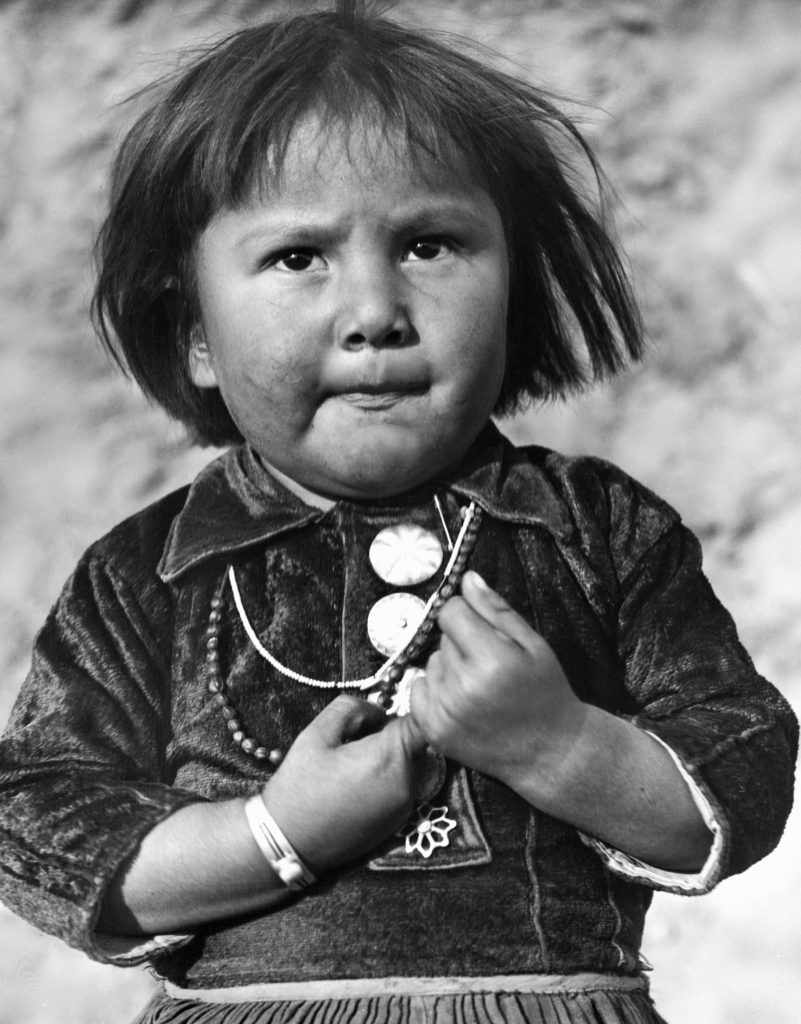

Barry M. Goldwater, “Native American Child,” 1956; Courtesy of the Barry & Peggy Goldwater Foundation

It would be easy to approach this exhibition with a healthy dose of cynicism. Would this show even exist if Barry Goldwater wasn’t Barry Goldwater? Do the photos on display exhibit signs of artistic depth and true skill, or are they the work of a prolific hobbyist – someone whose work is appreciated because of his considerable reputation as a businessman and politician?

The short answer to these questions: Yes, the work itself is actually really good. Goldwater’s black-and-white shots, in particular, are stunning. He captures the beauty of the desert in monochromatic frames that recall the work of film director John Ford. With masses of silvery clouds sweeping across an expansive sky that looms over jutting cliff faces, “Valley of the Monuments, 1967” in particular feels like it was cut out of a scene from Stagecoach or My Darling Clementine.

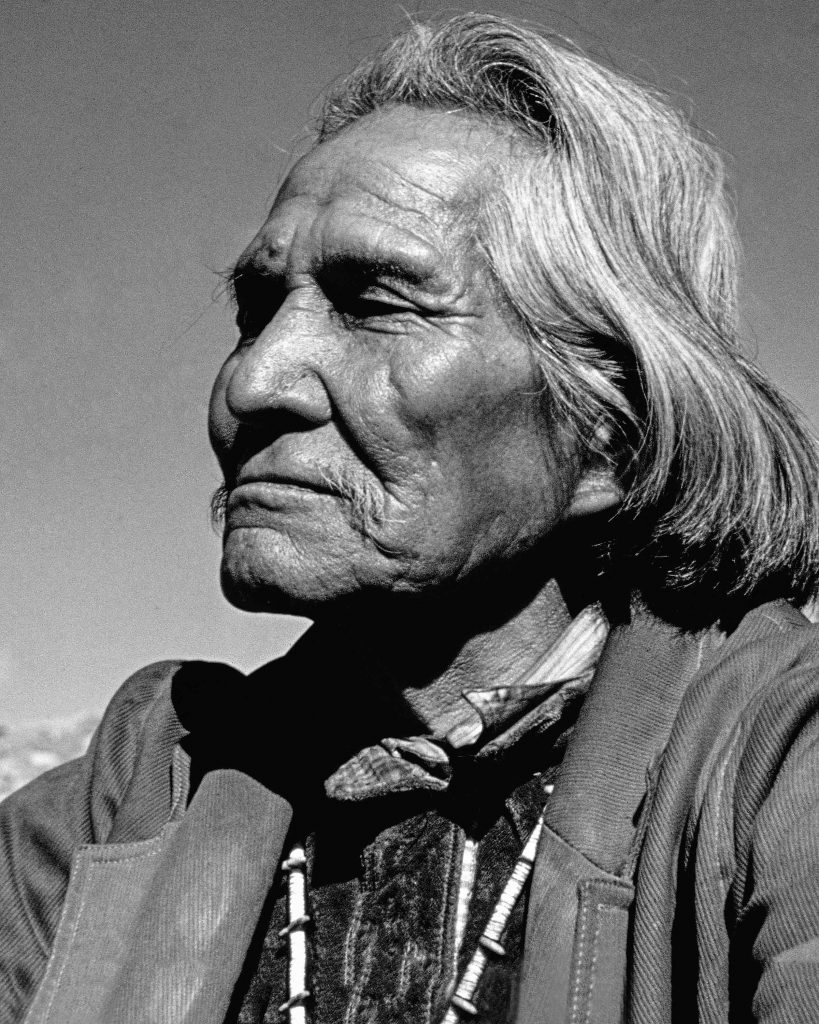

Tree branches heavy with snow, flocks of sheep milling on an unpaved road that’s cut through the center of a desolate field, a rotting wagon wheel standing tall and proud in the desert: Goldwater’s photos capture the beauty of nature in a melancholy, somber light. He also took photos of Navajo and Hopi that he encountered and befriended over the years, waxing lyrical in his descriptions about their “great dignity and great wisdom.”

There isn’t any kind of tangible political intent or content on display in any of these photos. This isn’t Goldwater the small-government conservative behind the camera. It’s Goldwater the historian, the naturalist, the man who spent a good portion of his life documenting the vanishing West.

And yet: It’s hard not to think about politics while looking at Goldwater’s lovely shots of Navajo spinsters at work or tall, snow-capped mountains. The gulf that exists between the kind of conservative Goldwater was and the ones in power now seems so wide as to be unbridgeable. Could you imagine someone like Mitch McConnell taking artistic photos for kicks?

Looking at “Desert Corsage, 1936,” Goldwater’s beautiful close-up of a cactus blossom, it’s easy to buy into this vision of Goldwater as the kinder, gentler conservative. But it’s important to remember that this is the man whose decision to vote against the Civil Rights Act (based on an unyielding belief in small government) helped kick-start the “Southern Strategy” that encouraged the Republican Party to cultivate racists as a voting bloc.

So as much as one tries to focus on the photography, it’s hard not to think about these things. It’s hard to look at Goldwater’s rich, artfully composed shots of the natural world and not think about state parks being vandalized and neglected during the government shutdown.

Barry M. Goldwater, “Valley of the Monuments,” 1967; Courtesy of the Barry & Peggy Goldwater Foundation

It’s hard to look at photos of noble, wise Native Americans and not think of them being yelled at by adolescent punks in red hats. It’s hard to gaze at the shadows of mountains in the backgrounds of Barry Goldwater’s photographs and not think about an oil exec surveying the same landscape, wondering just how much oil can be ripped out of it.

They are lovely photos. There’s no doubt about that. Goldwater knew his way around a shutter.

Photographs by Barry M. Goldwater: The Arizona Highways Collection

Through June 23

Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West

scottsdalemuseumwest.org

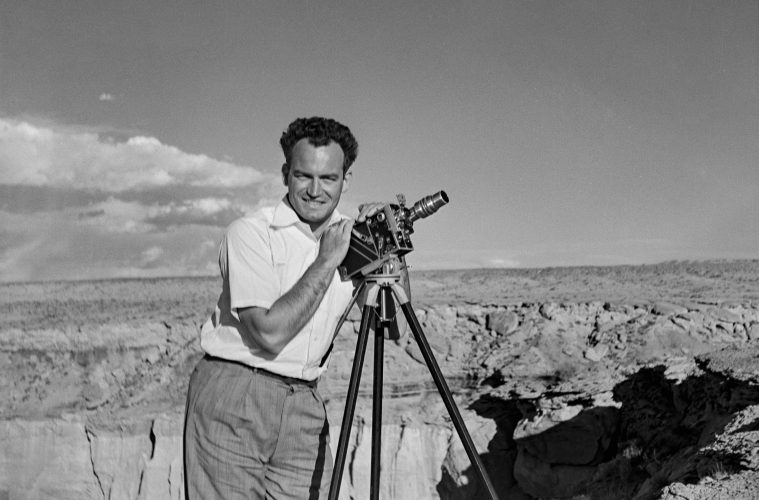

*Featured image credit:

“Portrait of the Artist as a Married Man,” Taken at Coal Mine Canyon between Tuba City and Third Mesa, c. 1935. Photo by Peggy Goldwater. Courtesy of the Barry & Peggy Goldwater Foundation.