Walking through Maria Hupfield’s exhibition at the Heard Museum, I have the uncanny sensation of there being many more bodies in the room with me. An army of 2x4s are leaned against a wall at a generous angle. A doughy gray sculpture is crumpled on the floor, strung up like a whale by its tail. Costumes made with chainmail, latex, and beads stand shoulder to shoulder, draped over the abbreviated version of clothing racks. The docents and I circle around the works and each other.

Hupfield’s monographic exhibition with forty-some works condenses the last nine years of her central political project as an Indigenous (Anishinaabek) femme artist. Hupfield’s practice spans sculpture, video, and performance, underwritten by a material lexicon. The exhibition demonstrates her investment in certain materials: raw felt and unpainted 2x4s are used repeatedly, as well as a fluorescent warning-sign yellow. Iconographic Indigenous objects, as with the canoe form “Jiimaan” (2015), are replicated with these distinctly industrial materials. A pair of boots made from animal hide would be considered an object of anthropological study; Hupfield’s boots made from felt are a rebuttal against stereotypes that tie traditional materials and craftwork to western valuation of Indigenous work.

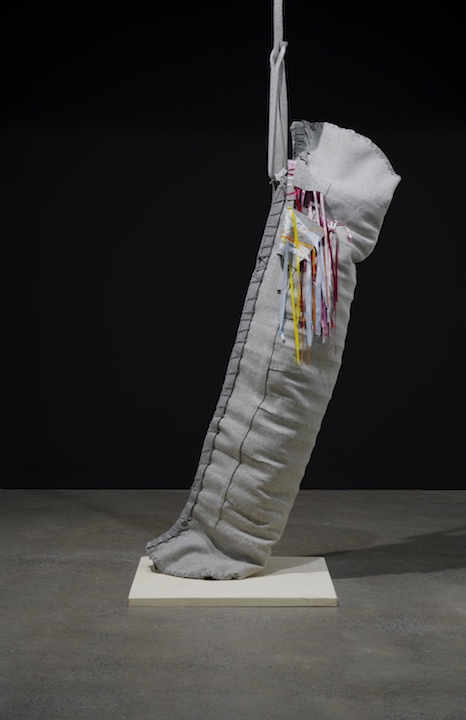

Many of the exhibition’s replica works are objects made for the human body. A pair of boots look like rounded feet, a set of deck chairs (à la Rietveld) look like a reclining couple, and costumes Hupfield made for herself, hung over clothes racks, appear to be draped over the shoulders. I begin to realize why I feel like there are other bodies in the room with me. It’s funny how objects made to accomodate the human body will mimic its form. Sculptural costume pieces like “Crystal Vest” (2014) and “Guts + Fringe” (2011–) were made for Hupfield to wear for her performances. Each of these stands on its own rack with wheels fixed to the base, suggesting that they could be wheeled out at any moment for a performance. These works create a bodily presence without describing the human figure directly.

Certain pieces make palpable the absence of a body rather than its presence. “Missing Bear I, II, III” (2014) is a set of posters Hupfield made after one of her costume pieces was stolen following a performance. The poster shows Hupfield wearing a burlap bag over her head – present but anonymous. This open and unresolved search for a missing presence parallels the ongoing search for missing and murdered Indigenous women. “Vestige Vagabond” (2012) suggests the outfits and attitude that Hupfield and collaborator Charlene Vickersis inhabited for a performance of the same name. A pair of jersey tank tops, Sony Walkman players, and braided wigs are fixed flatly against ply boards. It’s a to-scale illustration of the performance that suggests not only their bodies but their bodies in motion – the swing of their braids, the beat of the music, their movements uninhibited by the loose jersey tops. Bodies and art objects begin to suggest the same potential for performance.

Hupfield’s performance and collaborative practice underscores the function of the works on display. Remances from past performances or pieces that suggest future collaborations require an imaginative space in order to bring their true potential to light. On the second floor, documentation from opening night is on display. Hupfield takes pieces of 2×4 from the installation downstairs and activates them as part of her opening-night performance. These objects on display are defined by this potential activation by Hupfield. It should be recognized that performance is an in-the-moment experience and impossible to capture with documentation. Nevertheless, I begin to realize the key absence in the show is of Hupfield herself, and just how different these objects on display are without her there to activate them. Without Hupfield, much is missing from view.

This sense of the maker’s absence expands the scope of my thinking to include the rest of the museum. In another part of the building, the museum’s collection of kachina dolls is on display. Despite having little or no accompanying text, the undeniable uniqueness of each doll communicates the presence of individuality; I can easily imagine a child for each doll. I cannot say the same for the David Hockney’s Yosemite and Masters of California Basketry. Hockney alone is the active agent in this exhibition; I can’t sense the same for the Indigenous basket weavers.

Hupfield’s exhibition raises questions about authorship and anonymity, activating presence or performative absence – both within and without the institution. This is a question with political stakes for Indigenous artists, especially when it is noted that what Indigenous history has not been erased now largely remains with collecting institutions. Artists like Hupfield are uniquely positioned to expand our ideas of continuity and institutional historicism. Thank you, Maria Hupfield, for helping me arrive at these questions.

Maria Hupfield: Nine Years Towards the Sun

December 6, 2019 – May 3, 2020

Heard Museum

2301 N. Central Ave., Phoenix

heard.org