Annie Pootoogook (Inuit) , “A Portrait of Pitseolak,” 2003-04 , Pencil Crayon, Ink , 26″ x 20″ , Courtesy Edward J. Guarino Collection

When one thinks of contemporary art, the assumption is that it comes from “the now.” So SMoCA’s current exhibition of works by an artist who was born in 1904 and most active 70 years ago is unexpected.

Meet Pitseolak Ashoona, the grandmother and matriarch of a family of artists that included several strong women. Akunnittinni: A Kinngait Family Portrait features her work, along with that of her daughter Napachie Pootoogook and granddaughter Annie Pootoogook.

The curator of the exhibit, Andrea Hanley, Membership and Program Manager at the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts in Santa Fe. “This exhibition serves as a reflection on the role of narrative between three generations of women from one family,” Hanley says. “If you are standing in the gallery, you really feel this conversation between these women.”

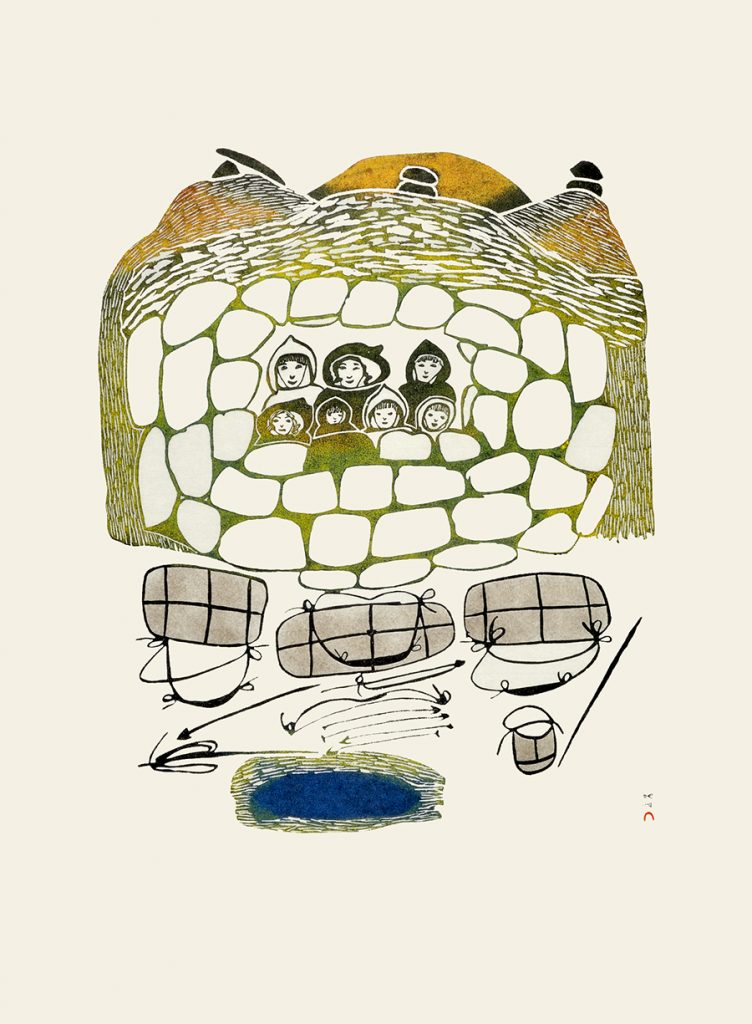

Pitseolak Ashoona (Inuit), 1904-1983, “Family Camping In Tuniq Ruins,” 1976, Stonecut & Stencil, 33 3/4 x 24 3/4”, Courtesy Dorset Fine Arts

Hanley first designed the show for IAIA, pulling six images from each artist. She had been familiar with Annie Pootoogook’s work for a very long time. But when she visited a private collector, Edward J. Guarino, a retired schoolteacher from New York, he showed her hundreds of images by Annie’s mother and grandmother. Hanley began to see connections between the women in their work; their relationship revealed itself piece by piece.

Akunnittinni, in the Inuit language, translates as “between us.” Hanley’s own heritage as a Navajo woman, coming from another matriarch-led Native American culture, helped her connect to the multigenerational nature of the works. Hanley also has a Valley connection; she grew up in Tempe, worked at the Heard Museum and managed the Berlin Gallery. She also worked for almost a decade at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C.

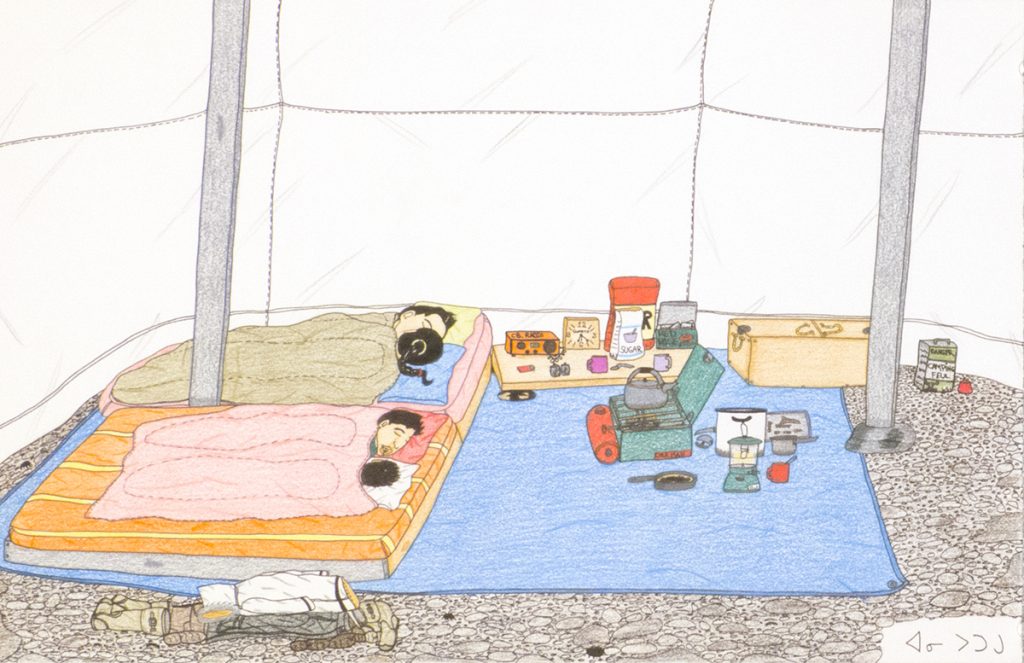

Annie Pootoogook (Inuit), “Family Sleeping in a Tent,” 2003-2004, pencil, ink, and pencil crayon, Courtesy Museum of Contemporary Native Arts

In addition to borrowing from Guarino’s collection, the exhibit also draws from Dorset Fine Arts, which has represented Inuit artists of the West Baffin Eskimo artist cooperative since 1978. The Cape Dorset arts community in Canada is known as “the capital of Inuit art,” Hanley says.

Annie Pootoogook’s art is probably best known of the three women’s work. In 2006, Annie was awarded the Sobey for art from the National Galley of Canada, along with a $50,000 top prize. Her work has been shown in dozens of exhibitions throughout the years, and Annie was featured in the Documenta12 exhibition in Kassel, Germany (2007).

Some of Annie’s drawings are childlike, remembrances from formative moments in her young life, drawn in colored pencil with black outline. One touching print shows just her grandmother’s thick-rimmed glasses. The item on its own is so representative of Pitseolak, it almost seems she could be in the room.

Napachie Pootoogook has a somewhat more sophisticated hand, creating stone-etching prints with lots of depth and shading. Pitseolak Ashoona’s images look more familiar, like the representative Inuit art one might see in an airport gift shop in Juneau. All three women have had amazing careers, Hanley says. And none of them received formal training in stone etching or drawing; their artistic training was passed down through the family.

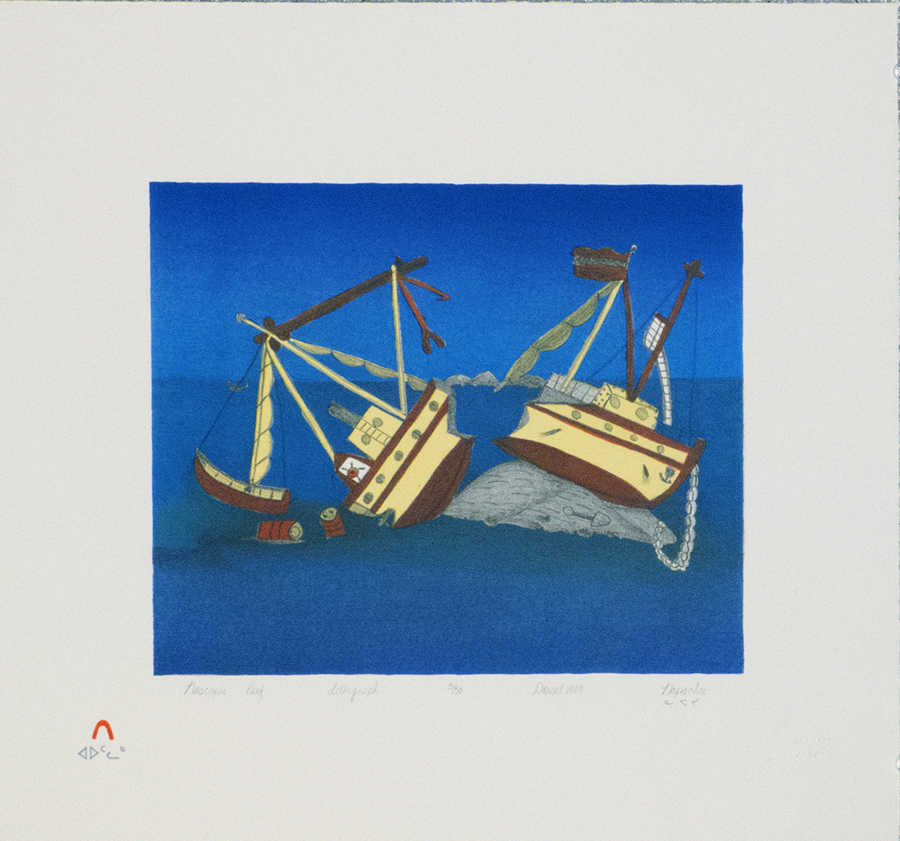

Napachie Pootoogook (Inuit), 1938-2002, “Nascopie Reef,” 1989, Lithograph , 17″ x 19″ , Courtesy Edward J. Guarino Collection

Pitseolak Ashoona was widowed at a young age and over the years was responsible for caring for 17 children, only six of whom lived to adulthood. Hanley says that Pitseolak looked at printmaking as a way of earning a living. The Cape Dorset group provided Inuit families a way to earn an income after the fur trade declined.

Pitseolak began working in this art form in her 50s, and then she became prolific, making thousands of drawings and prints in her lifetime. She received the Order of Canada in 1977 and was the subject of a number of documentaries and books. The National Film Board of Canada produced a film based on one of those books, Pitseolak: Pictures of My Life.

While Pitseolak tended to create images of things very representative of Inuit culture and reminders of days that have passed, Napachie captured many contemporary issues and even the struggles of her community. Many of her works are feminist, and some tackle hard-to-discuss topics, such as domestic violence, human trafficking and even cannibalism. “You see the survival, you see the resilience of indigenous women, in such an isolated place. Not necessarily what was happening to her, but what was happening in this place,” Hanley says.

Pitseolak Ashoona (Inuit), 1904-1983, “Dogs Eat the Seal,” 1981, Stonecut & Stencil, 16 1/2 x 19”, Courtesy Dorset Fine Arts

“We have never had a three-generation show,” says SMoCA’s implementing curator, Claire Carter. “And the fact that it was matriarchal was intriguing to us, as well.” Carter explains that the show is small and intimate by design. Having only 18 selections from the thousands of works these women produced helps put the pieces into a more streamlined dialogue.

Pitseolak’s “Dream of Motherhood” shows a woman with another, smaller woman on her head, who is carrying a child in an amauti, an Inuit parka designed for carrying a baby on the mother’s back. One can imagine the three generations of women in this vision.

Akunnittinni: A Kinngait Family Portrait

February 3 through May 27

Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art (SMoCA)

www.smoca.org