Art is about things seen and unseen, objects that open and close to experience as well as encounters that we may recall for a day, a week, a month, a year, and even for a whole lifetime. The most recent exhibition at Lisa Sette gallery, entitled “Things We Carry,” plays with all of these expectations and subverts some of our most commonplace ideas about objecthood.

A three-person exhibition that showcases the works of Angela Ellsworth alongside the collaborative endeavors of Merryn Alaka and Sam Fresquez, we find a shared space of concerns that constitutes a stunning duet of projects that shimmer and shine throughout the whole of the gallery. What is even more compelling than the formal resonance between the works in this show, however, is the confluence of theoretical concerns that underpin the motives behind these different artistic projects.

Ellsworth’s art practice has long been committed to investigating and subverting the traditional expectations of women within regard to the roles assigned to them by religion – the dictates of Mormonism in particular. But with this show, Ellsworth provides us with an entirely new twist on her project by combining secular iconography with religious themes. Here her pantaloncini forms, which refer to a specific style of shorts that were worn by both men and women, have a distinct colonial history – the word itself refers to British and French military uniforms that have been naturalized as a style of civilian dress with the passing of time.

This causal wear has been meticulously reconstructed by Ellsworth using pearl corsage and dress pins mixed with fabric and steel substrates that bare a resemblance to the undergarments associated with Mormonism. Each is adorned with arcane symbolism reminiscent of the lapels of a high-ranking military officer. Thus presenting an outward expression of signs that are revealed rather than concealed, where religious signifiers are used to demonstrate the many ways that belief systems can be pinned to us, not to mention how we can be hemmed in by rigid social rituals and prescriptive identifications.

While art lovers may be familiar with these aspects of Ellsworth’s oeuvre, her new work departs from past themes in the choice of pantaloncini forms that are not inscribed as religious garments, but instead reference the geographic locations where Ellsworth photographed the colors and patterns that appear on these pieces, often as a revelation of journeying through the arid Arizona landscape.

Acting as a modern cipher of a sorts, Ellsworth’s pieces point to the cryptic nature of found symbols, something that ties her wandering discoveries to the golden plates of Joseph Smith, as well as Hermes Trismegistus, who gave us the saying, “as above, so below,” a phrase that figures into Ellsworth’s titles by connecting GPS coordinates given from on high with trace inscriptions found on the ground. Yet, the concrete nature of these references still ask us to look a deeper into the consequences of hermeticism itself.

There is an implicit critique of the patriarchal founders of many modern-day religions, in that every form of belief is a hermetic game of sorts where one must adopt a series of principles in order to understand the rules that govern meaning. Pantaloncini is the masculine plural form of pantaloncino, which implies the need to examine how certain groups hold privilege in society. While the plates of Smith and the inscriptions of Hermes have never been located, much like those other fabled tablets of Moses or even the writings of Jesus, this choice of gendered denotation suggests seeing the history of religion, not just with the shoe on the other foot, but with a different set of prophets wearing the pants so to speak, especially when it comes to re-examining the validity claims of both physical and metaphysical assertions.

In this way, Ellsworth’s “Seer Bonnets” and the piece entitled “Chiarvoeggente” – which loosely translates as clairvoyant or visionary – also implies a different sense of narrative, one engaged in reflecting on the world as it is, without the use of mystification. This ability to tarry in a space of experience, absent mythos, provides us with a critique of the kind of found objects – or rather, unfound objects – upon which many religious revelations are based.

Instead, Ellsworth’s work focuses on things that can be found, including signs of symbols that are inscribed upon the earth as a material substrate, and even as a maternal body. There is a parallel in that the garments of Gaia have been forced to bare traces of anthropocentric designs in much the same way that the feminine body has been burdened with so many patriarchal symbols of ownership, rights and enforced commitments around the consecration of beliefs. What Ellsworth’s work helps to highlight about these juxtapositions in the exercise of patriarchal power is that all of this has occurred not just in the last few centuries, but even across the last few millennia without so much as a concrete trace of the primary documents upon which such abuses are justified.

——————————————————————————————————————

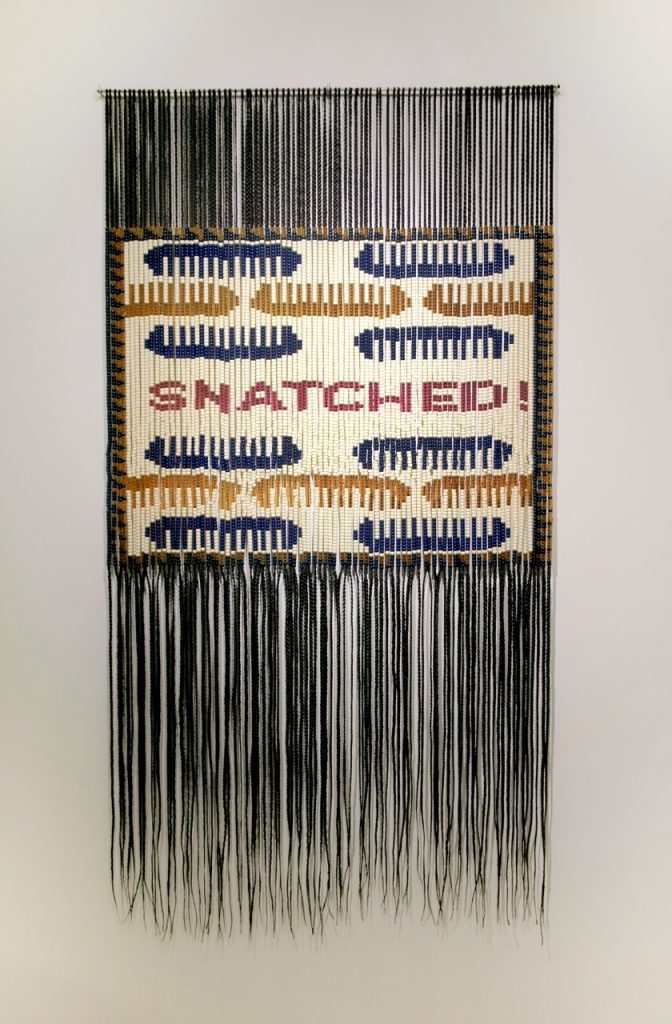

By contrast, Alaka and Fresquez are both engaged in similar questions, but from a very different set of perspectives. If their forms resemble any past cultures and religious motifs, it is perhaps Egyptian aesthetics with broad smooth forms, eloquent designs, and the sheer power of monumentality, in pieces like the “Notorious W I G,” “Bundles Past My Butt” and “My Beauty Supply Thinks I’m a Slut.” Yet, one must immediately note how these titles diverge from questions regarding past aesthetics by being grounded in cultural debates about the present, and especially about the politics of self-presentation.

The repressive aspects of enculturation and the style industry are now more widely recognized than ever, especially in the wake of films like Good Hair, Self Made and Nappily Every After, which have all worked to thematize the labor behind meeting certain societal expectations for women, and the process of beautification for black women in particular. That there is not just a significant cost to the cult of care that women endure as subjects of patriarchy plays an important role in the conception of Alaka and Fresquez’s works, along with the fact that the investment and time commitment needed to achieve such goals is often doubled, tripled and even quadrupled for black women and other minority communities.

The deeper realization here is that the dedication required by these rituals of self-care nearly elevates them to the status of an imposed religion in their own right. This is because both institutions bare the common expectation of large and regular monetary donations, long and often painful rites of regulated redress, along with the implications accorded to social and professional acumen in regard to achieving an entire host of desired effects. Moreover, when such standards of presentment are not undertaken, the result is often cultural exoticization or spoken acts of othering rather than acceptance, or even unwanted touching rather than respecting the space and positive affirmation of bodies.

In this regard, the work of Alaka and Fresquez challenges these prejudices through the production of weighty chandelier-like forms that demand to hold space in a room along with the sophisticated articulation of so many streaming bulbs of vertical hair bobs that must be delicately negotiated in order not to disturb the active play of design and dissemblance. In this way, we can say that Alaka and Fresquez’s work speaks to the growing concerns around routines and rituals that have been naturalized over the generations in an entirely different way than the pieces of Ellsworth that are decidedly more discreet in their interests and intimate in scale.

If Ellsworth’s part of this exhibition is about questioning those beliefs that appear to be sewn into the fabric of different religious ideologies, then Alaka and Fresquez’s collaborations are about embracing counter-narratives to the status quo. Alaka and Fresquez’s work challenges the dictates of white supremacy with regard to the act of taking up space, indexing the gordian knot between history and repression that is tied up in the suspension of our everyday expectations of encountering difference as such.

In this way, we can say that all three artists in this exhibition act as seers, as visionaries in the field of cultural interventionism. Toward this end, “Things We Carry” is not just about how the burdens of the past circumscribe the dictates of the present, but how these two bodies of work are actively engaged in undoing the kind of presuppositions that have structured the systematic abuse and systemic domination of BIPOC, gay, lesbian and queer peoples.

It is no coincidence that an exhibition that speaks to these concerns is full of pins, needles, knots and even rope-like forms, all of which speak to histories of disciplining the body. Most importantly however, are the numerous ways that these works talk about how bodies can be rendered invisible by power and prejudice, as well as how they work to reclaim a space of unfettered presentment through a palpable sense of opulence and presence.

To see these works in person is to visit a space of liberatory potentials made real, of histories revised and re-evaluated. One gains entrance into a space of contemplation that trades on the genuine power of artistic expression to reconfigure our relationship with the world around us.