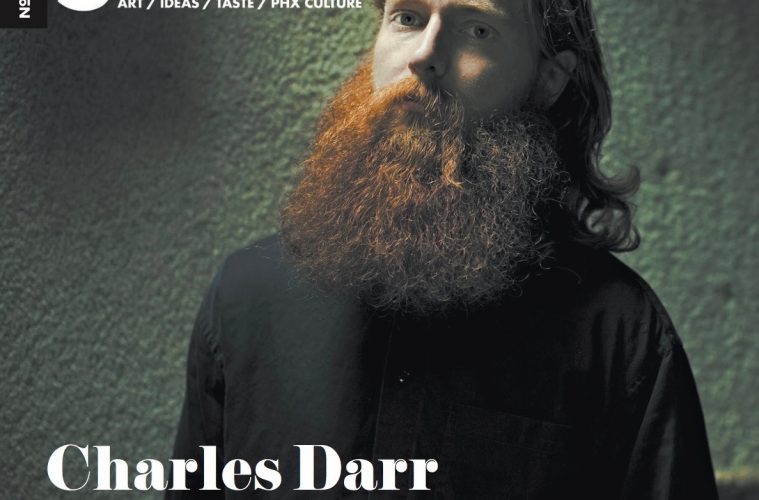

Charles Darr is hesitant to call himself an artist. Instead, he offers theories on what it means to be one—to create work and to share it with an audience that both changes and is changed by the work. He identifies with the adage that art is an ongoing conversation, or at least a number of conversations occurring simultaneously, but he remains uncertain of where his voice fits in to any of them. In his ongoing series, “Stars to Satellites,” he has found a place by documenting the artists and people of Phoenix who inspire him.

In the past three years, Darr has shot more than 60 portraits of individuals who, for one reason or another, represent what it means to be dedicated to a craft or idea. “The people I’m photographing aren’t limited to artists—they are also activists, thinkers, entrepreneurs,” Darr said. The subjects are pillars of Phoenix’s creative community and disprove the lingering notion that Phoenix’s creative class, while noteworthy, pales in comparison to those of other large cities. But Darr’s inspiration for the series came from his own personal frustration. While he grappled with questions of what it means to call himself an artist, he gravitated toward people who served as examples.

Darr was born and raised in Maryvale, a suburb of Phoenix that has become known for gang violence and urban blight. This is where he first discovered photography through his fascination for family photos. “Growing up, my first experience with photography was just looking through my mom’s memories. I’m just trying to record my own,” he said. His parents saved enough money each year for a summer vacation, usually spent in the National Parks. It was during one of these trips that Darr was first allowed to hold his parents’ camera, capturing the landscapes and the sensations they induced.

As a teenager, Darr found a use for his photography through skateboarding: shooting videos of friends for Cowtown Skateboards. “All my friends were always better than me at skateboarding, so I was usually the one [filming],” he conceded. Then, after his camcorder was stolen, he bought his first digital camera in 2003 and rarely went anywhere without it.

Darr enrolled at ASU, where he met some of the professors and cohorts who continue to influence him today. Through faculty such as Michael Lundgren, who has taught at ASU since 2004, Darr was exposed to the life of a practicing photographer. He began to appreciate what it means to put a craft at the center of one’s universe—to develop in darkrooms and to submit to journals and gallery exhibitions constantly.

Darr realized that going to college wasn’t a necessary part of the equation, so in his second year at ASU he decided to drop out. “My most influential teacher inadvertently talked me out of going to college at that time,” Darr chuckled, speaking of Lundgren. However, Darr returned years later, at the age of 27, and enrolled in ASU’s photography program, where some of the students he’d met the first time had now joined the ranks as faculty members.

Darr was then better suited for the intellectual rigor of academic life. He encountered the work and ideas of many photographers, explored what it meant to be an artist and contemplated photography’s role in contemporary society. “A lot of people hold [photography] to this standard, like painting, as if can you make a photograph as beautiful as a painting. But I don’t think those are the most interesting photographs. Photography is sufficient on its own. It doesn’t need to emulate another medium,” Darr said. He found relevance in the works of Stephen Shore, whose 1982 book Uncommon Places captures the mundane qualities of American life without injecting glamour or beauty.

It was during this time that Darr took a portraiture class with Betsy Schneider, laying the foundation for his “Stars to Satellites” series. He hadn’t taken many portraits prior to this, and was instead focused more on capturing fleeting moments.

After Darr graduated from ASU, he struggled to stay motivated. “All the work that I did in college was just responding intuitively to the stimulation around me,” he explained. “A couple years after graduation, when you’re not in that environment anymore, you don’t really have that inspiration.”

A post-graduation existential crisis set in. If art is an ongoing dialogue, at least school placed Darr within the conversation. Once he graduated, he was on the outside, wondering if he had anything to contribute. “If you just shout into the void every now and then, you’re not really part of the discussion,” he says. “I wasn’t feeling like much of a photographer.”

To break through his self-doubt, he started reaching out to friends that he wanted to photograph. “So then you have to get off your ass and seek it out, and you have to start contacting people, like, ‘Can I come over and shoot photos with you?’” he said. The first person in his portrait series was Christian Michael Filardo, a former Tempe-based audio and visual artist now living in Santa Fe, NM. The photo features Filardo surrounded by boxes of cassette tapes and recorders for HOLY PAGE, his experimental music label.

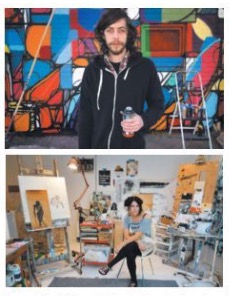

“After starting this project, I began pushing my comfort level with regard to how much I wanted to direct a photograph as opposed to just capturing something,” Darr said. He might move an object out of the frame or shift a chair a few inches to improve the composition, creating a balance between the candid and the curated.

The entire series is shot with a first-generation Sony RX digital camera. It is small and discreet, in contrast to the bulky DSLR or lighting equipment some subjects expect Darr to bring. “It’s not really about the hammer and the saw, it’s about the structure you build,” he explains. “I’m very big on the final product and not the tools that got you there.” When shooting a portrait, he’s able to engage with the subject without hiding behind the lens and viewfinder. His process is simple, and he often observes the space for only a few minutes before knowing how to proceed.

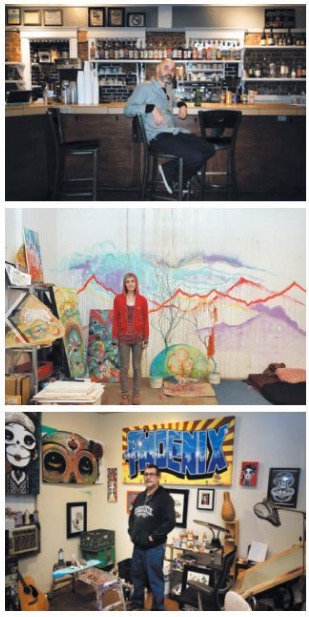

“Stars to Satellites” has retained an intimate, engaging aesthetic throughout the series. Darr invites viewers into the creative refuge of the subject’s home. There is an element of voyeurism as a sense of privacy falls away. He brings you in, but the subjects themselves at times appear wary and unsure of how to pose in the very space where they should feel most comfortable. Some spaces are cluttered, others clean and well organized, each revealing the nuances of the individual pictured.

Many of the subjects are easily recognizable to anyone familiar with the Phoenix arts community—Tato Caraveo, Lalo Cota and Sierra Joy, to name a few.

For Darr, they are friends, colleagues, former professors and other important figures in his life, who act as pieces of the puzzle.

What does it mean to be an artist? Darr’s portraits have brought him closer to creating his own definition. “I’ve become more educated on what being an artist means and have gained a unique insight by going to artists’ spaces and talking to them about their process and their vision,” he said.

This is a collection of people whom the 35-year-old Darr aspires to, because of their work ethic and passion. They are the stars and Darr is their satellite, orbiting around them. While the series is ongoing, he has no end goal in mind, except one: to look at these portraits years from now and remember the people who inspired him. “Down the road when it’s all over,” Darr says, “I’m going to be happy that it was documented and recorded.”

www.chardarr.com