Carolina Aranibar-Fernandez comes to Arizona from Bolivia, where she started her life of art at the age of eight. Her passion and work are driven by the mapped relationship between people, capital, and place, and fueled by history and current events.

Bolivia’s famous Water War was one of the sparks for Aranibar-Fernandez’s body of work, in which she questions systems of colonization, capitalism, commodification, and extraction. She grew up at the time California-based Bechtel took control of her country’s water and spiked the rates, causing outrage and protest among Bolivians. She found herself questioning, then and years after, how a company so far away from a community could have so much power over it.

Ten years ago, she left Bolivia to attend art school in the United States. Since then, her questions and art have taken her to Virginia, Qatar, Nepal, the Amazon, Brazil, back to Bolivia, and Arizona, and will take her soon to Florida.

In each place her work leads her, she first waits for an invitation to enter the space. She comes to collaborate, not to work. She takes care not to perpetuate the colonialist habit of self-inserting and forcefully exploring for the sake of art. Instead, she builds relationships with the community, asks questions, and listens. Her goal is to create dialogue and form connections with the viewers of her pieces as well as with the communities with which she collaborates. Sometimes she engages in with a community for over a year before starting a piece – or doesn’t start a piece at all.

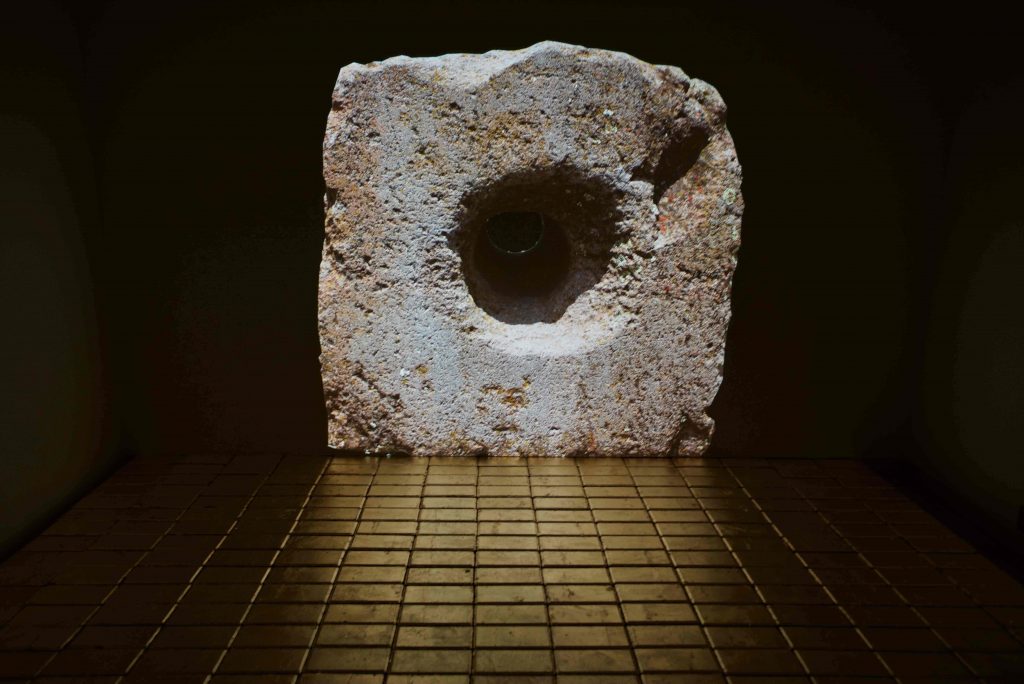

Her work projects questions of power and how it manifests. Often formed as multi-media installations, Aranibar-Fernandez’s art immerses viewers into the behind-the-scenes world of production and extraction. She creates rooms that illustrate, by engaging almost every sense, the duality of a journey – between commodity and person – out of the earth, through the sea, and into a foreign land. Video projections and audio composites are mixed with textiles, ceramics, weaving, and beading, merging traditional forms of storytelling and creation with more contemporary and processed media.

As an artist within an imperialistic, neocolonialist, and capitalistic society, she strives to exist inside – but against – this system, or, as the Peruvian sociologist Aníbal Quijano asserts, “vivir adentro y en contra.”

This is demonstrated aptly through her exhibited work, commonly installed in colonial institutions (art galleries). Viewers unwittingly participate in destroying the work they experience, dropping its perceived value rapidly – sometimes simply by walking into the room. No single piece she has made still exists in physical form, to reject any attempts at commodifying an art piece made to question commodification.

The unperceived value of her work is her process. Vulnerability threads itself into her regimen as she visits male-dominated mining sites through discomfort during deep dives into research. She also embraces vulnerability to ensure her work reflects the experiences of others above her own. Whether it’s silver-leafed coins made of quinoa and cocoa in Bolivia, or sugar molded in Brazil to model gold bars, Aranibar-Fernandez makes a point to work with those impacted by exploitation of these commodities as she fabricates her pieces. Each small part of the work is painstakingly handmade in collaboration with local working-class women of color, who engage in hours and hours of dialogue with her that in turn informs the rest of her process, from beginning to end.

The women in these communities are crucial to Aranibar-Fernandez’s messages. They are directly impacted by the exploitation of their countries’ resources, be it minerals and food commodities in Bolivia and Brazil, physical labor in Nepal, or oil and gas in Qatar. They are, as she affirms, the “most invisible labor.” She not only collaborates with them to make her work but also illustrates their stories visually and aurally.

Women also exhibit a more ideal distribution of power than what is seen in the typical realm of capitalism.

“If power is not only a ladder, rather a web, I think we could move differently in the world. And I think a lot of decisions in the capitalist system that we live in create an individual, egotistical ladder that I find very problematic.” Aranibar-Fernandez continues, “Redistributing power is really important. And in thinking about community, women have – for thousands of years – shown that when you work in community, there’s no ladder in the structure of power.”

Elevating women and sharing their histories is only one, albeit a significant, facet of Aranibar-Fernandez’s work. She also wants to introduce people to the layers of place, and to give thought to how hierarchies of power shape history and mythology.

“Space – every place we go, and every land we step – has layers of history,” she explains, and her intent is to uncover the history not rewritten by colonists but shared by the people who were born and raised on the land – those who live here today and their ancestors. History indigenous to many of the places Aranibar-Fernandez has visited is considered mythology by Westerners, who use their position of power to frame their own narratives as objective history and discredit others. Aranibar-Fernandez learns as much as she can about the history of a place through reading, as well as through oral stories told by members of the communities she collaborates with, before settling on an idea for a project.

She also uses place to differentiate forms of movement and exploitation. On the land, she analyzes resource extraction in mining, agriculture, and construction. But she also uses place as negative space – an opportunity to discusswhat’s between places. That is why her work has also always been rooted in and across bodies of water; she is, in many of her pieces, “exploring depth in the ocean.”

Perhaps Bolivia’s Water War served as a precursor to her consideration, as she has examined water as both a commodity and a plane on which to travel and to assert dominance. One of her first forays into this concept was working in and near the ports of Norfolk, Virginia, where she began to (and still to this day does) shed light on the trafficking of capital and bodies across the Atlantic.

While Aranibar-Fernandez is sharing insight into the backbreaking realm of extraction, she is also revealing the aftermath of it, both in the transport and the destination. Her work has taken viewers from the silver mines of South America across meticulously traced routes to the importing nations of Europe. She has tracked the traffic of blue-collar workers from Nepal to Qatar, where they are all but held hostage to build modernity on top of the rich history that once was there. She illuminates the consequences of destroying value to construct wealth.

In Arizona, Aranibar-Fernandez delves into the narrative of extraction with one of our state’s five Cs: copper.

Arizona’s copper mining narrative does not look quite like the silver mining narrative in Bolivia. Where, in the latter, the country’s resources were stripped to form another’s (Spain’s) currency, the modern-day copper narrative in Arizona represents one of dominance and control. Aranibar-Fernandez is delving into the power dynamics of copper companies that hold influence across the world, and she is only just starting to form her representation of it.

She has, since August of 2018, immersed herself in research and conversations revolving around copper, how its value is perceived across the globe, who takes it from the ground, where it goes, and who profits. As she unearths Arizona’s role in the mineral’s commodification, she is learning new things about her place in the world, as well as in her own family.

She discovered only recently that her grandfather was a miner in Bolivia, pulling from the earth silver and estaño(tin) in a small, rural town she had never previously considered visiting. Consistent with her usual form, the information came about through questioning and conversing with the town’s community.

During her time here, Aranibar-Fernandez has also developed a relationship with the Copper State that she has not established with any other place outside of Bolivia. She rejects any singular term to describe her identity (not simply an immigrant, not simply a Bolivian), and this emerges in her sentiments of belonging, as well. While she considers Bolivia a home due to her roots, family, and ancestors, Arizona has presented a similar feeling.

“I feel like since I’ve arrived, my body feels at home here, and that hasn’t happened before, in a place that wasn’t Bolivia. I feel that here. It seems like it comes from… I don’t know. I feel it really inside; it feels more like home. Arizona is very special.” Ancestral energy, the weather, the heat, and something still untouchable connect her to the state, in addition to human connections.

The politics of a border state has created a sense of belonging for her unwavering questions. The effect of power on place exhibits itself in the historic displacement of indigenous people and people of color for mining, and the contamination of tribal and reservation waters when minerals are washed of their toxicity. Like Bolivia, Brazil, Qatar, Nepal, and other disenfranchised countries, Arizona is not unfamiliar with this historical trend. But while it houses groups marginalized as a result of extraction and commodification, it also houses the agents who act to marginalize. In exploring the disparate nature of a place’s relationships, Aranibar-Fernandez’s art becomes as multidimensional as the histories and mythologies she works to unearth.

She views Phoenix as an important space for community and conversations. As with every place she has worked, she feels lucky to have mostly experienced receptivity to her art. She joins Arizona’s community through the ASU Herberger Institute’s Projecting All Voices Fellowship, which seeks to promote equity and inclusion in the arts by upholding spaces for discourse and representation. At the same time, any resistance, discomfort, or rejection of her work is viewed just as positively, and resounds with her own discomfort and vulnerability in making the pieces.

Aranibar-Fernandez has experienced the privatization of a country’s resources and the effects spurred from it, and she observes this still happening throughout the world, displacing and transporting people and things from one side of the ocean to the other. She can feel the state our society is in, and while conversations may be changing, she doesn’t think the structure is – at least, not fast enough.

With her work, she wants people to become conscious of the movement of people, resources, and narratives. Of those viewing her work, she doesn’t expect radical change, but smaller movements and conversations that may someday be catalysts to something larger.

“My biggest goal is to make and ask questions,” she concludes. “If every viewer can leave with a question, that’s amazing.”