Like water in the desert, art has the powerful ability to bring people together. In contemporary Phoenix, all too often, community-based art is reduced to branding and marketing efforts, and authenticity can quickly be lost. This city does, however, continue to bring people together beyond property and product. One recent powerful example of this is Vesich eth ve:m, a creative team that arose from the Water Public Art Challenge.

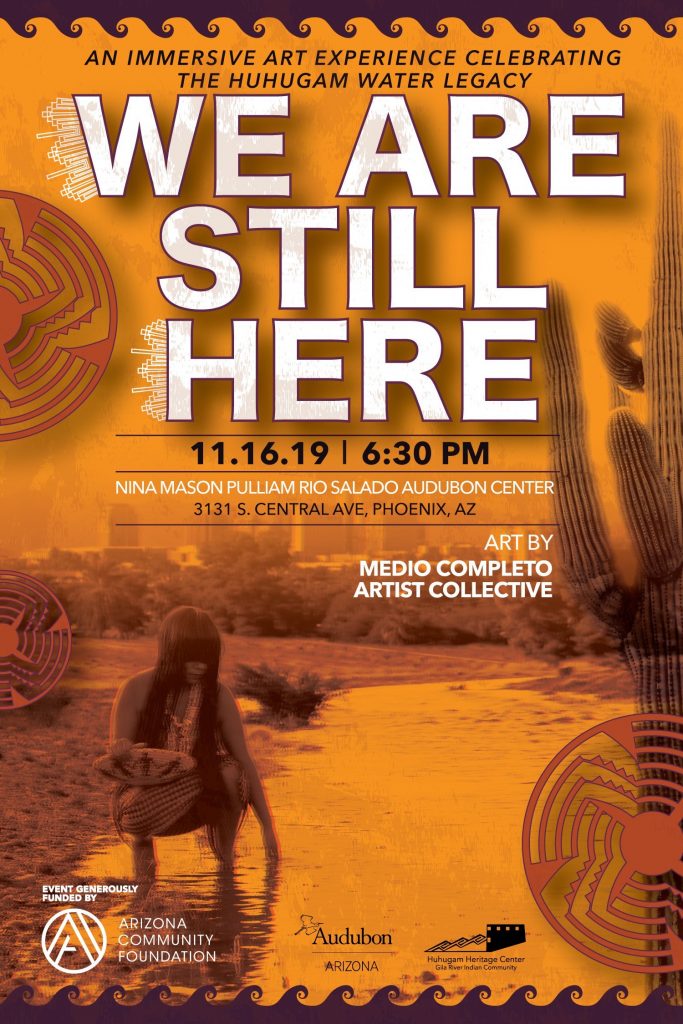

On May 30, 2018, the Arizona Community Foundation launched the Challenge – its third philanthropic competition “aimed at creating the Arizona of tomorrow.” Funds were distributed to collaborative projects that delved into the “Hohokam” legacy, canal system, and history of water use in the Valley. The majority of winning teams will be exhibiting their work on November 16 at Scottsdale’s Canal Convergence, the Mesa Arts Center, and the Rio Salado Audubon Center (with the exception of Pueblo Grande Museum’s exhibition, which was held on October 20).

The competition called for “collaborative temporary public art projects that build connectivity between cultures through creative expression.” Audubon Arizona’s executive director, Sonia Perillo, saw it as an opportunity to link water and community with the organization’s mission to protect birds and habitats. Birds, after all, need water.

Audubon Arizona is one of many nonprofits in South Phoenix looking for ways to connect with its community. Public meetings on the South Central light rail extension brought together many stakeholders, including Perillo and Sam Gomez of the Sagrado Galleria (located on south Central Ave.), and they began to discuss the possibility of collaboration.

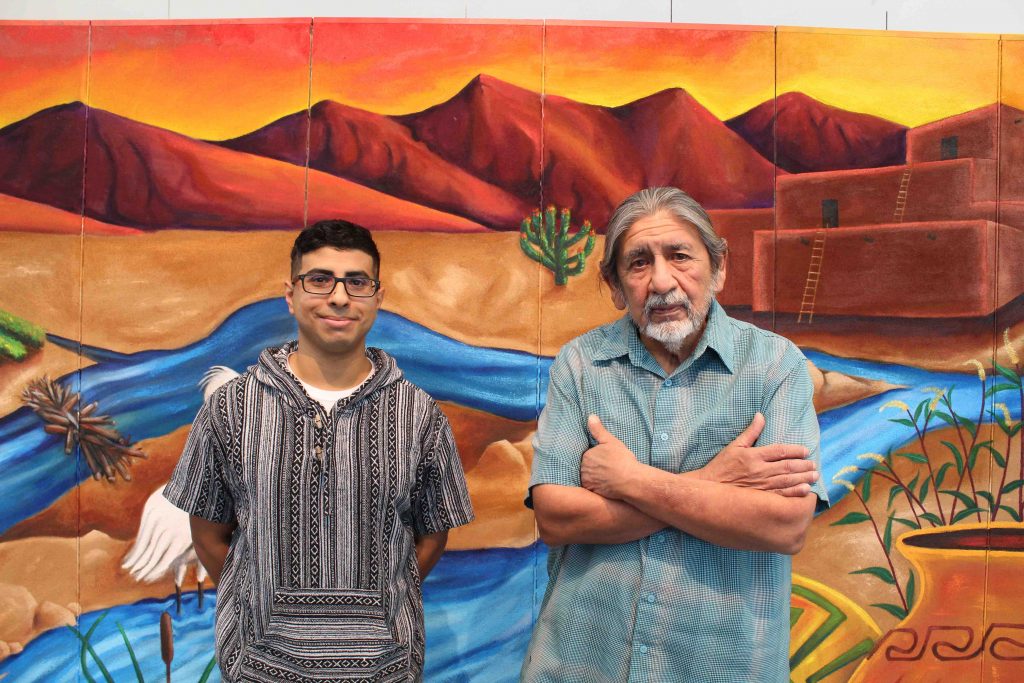

Meanwhile, a separate group was coalescing around Gomez. Diana Calderon, Gloria Martinez-Granados, Reggie Casillas, Nuvia Enriquez, and Ayo Sinplaneta were all looking to combine their individual artistic practices to form a collaborative. Soon enough, Edgar Fernandez and Martin Moreno joined the conversation, along with Gomez. Together they formed the artist group Medio Completo. Gomez then bridged Medio Completo with Audubon Arizona through the idea of the water competition.

Perillo was simultaneously reaching out to members of the Gila River Indian Community, which is composed of two tribes – the Akimel O’odham and the Pee Posh. In the past, tribal members had frequented the Rio Salado Audubon Center to collect materials for basket weaving.

The Huhugam Heritage Center was established to ensure that the Gila River tribes continue to flourish for generations. The center’s education curator, Monica King, says, “We want it for our community, but we also want to share with the public.” King connected with Perillo and signed on to the competition, inviting Heritage Center staff and artists from the community, including Joyce Hughes, Tim Terry Jr., and Aaron Sabori to contribute their vision and direction to the project.

Together Audubon Arizona, the Huhugam Heritage Center, and Medio Completo formed a team called Vesich eth ve:m, which translates to “all of us together.” Team members got together for the first time at the Rio Salado Audubon Center over a year ago to begin the application process, and since then have forged a path to share the results of their collaboration on November 16.

While all are interdisciplinary artists, Calderon and Martinez-Granados both currently work primarily through printmaking, Fernandez through painting and murals, and Casillas and Moreno through murals and sculptures. Enriquez and Sinplaneta are well known for their creation of La Phoenikera, an online bilingual publication covering Phoenix’s countercultures; they also bring experience with performance and film. Besides curating shows at the Sagrado, Gomez also works in photography.

The Medio Completo artists have approached the project from varying perspectives, but ultimately contrast with the Gila River and Heritage Center members in that they connect with the project through immigration – a common motif in the group – along with exploration of their ancestral roots. Many of the artists are immigrants or children of immigrants, and much of their professional work draws from their Latinx experiences. But in connecting with the Huhugam Heritage Center and members of the Gila River Indian Community, they learned not only about the living history of Phoenix’s tribal cultures, but also how easy it is to relate.

“It doesn’t feel that unfamiliar,” Calderon shares, “even though it’s not specific to my culture.” She reflects on her own family’s indigenous roots in the Copper Canyon in Chihuahua, Mexico. The sentiment is echoed by many Medio Completo artists, who find commonalities between their heritages and those of the O’odham.

The Medio Completo artists are familiar with community-based work – from Casillas and Moreno collaborating with others to make murals, to Calderon leading bookmaking workshops, and Enriquez and Sinplaneta cultivating the written form with La Phoenikera. Developing the work behind We Are Still Here was a new experience in that the artists effectively acted as students, learning how to accurately portray art expressing a historical and contemporary community.

We Are Still Here is an immersive art experience that presents a chronology of water history and features the importance of rivers for the sustenance of the Huhugam people. Through soundscapes, sculptures, augmented-reality murals, film projections, bookmaking, and performance, stories of Huhugam history are woven together with the community’s continued connection to the river. The artists aim to celebrate those who set the foundation for life in Phoenix and the surrounding communities.

Research took Vesich eth ve:m on trips to pick cholla buds, harvest cattails, attend storytelling sessions, and tour Pueblo Grande. The members also attended the dedication of the Gila River Indian Community’s MAR 5 (Managed Aquifer Recharge) Interpretive Trail, which presents a reminder of how water still does flow through the desert. Research trips were not led by disconnected historians but by living descendants of the Native Americans who built the extensive canal structure around the Salt and Gila Rivers.

“Each artist has had the opportunity to get feedback from the Huhugam Center, from the artists there, and from Monica and her staff,” Moreno explains. For example, Calderon consulted with artists on designs for her printmaking activity and with Hughes for translation of a poem to O’odham.

Sinplaneta shares that he connected to the project by “writing something that was approved, in a way, by the culture. I’m really kind of a tourist, and it could even be perceived as appropriation.” Learning about and listening to storytelling from community members enabled the Medio Completo artists to interpret their roles in the project. “We’re gathering stories that we’ve heard, and all this knowledge that we’ve been exposed to, and giving interpretation through our artistic sense,” Sinplaneta says. Ultimately, Medio Completo aims to bring the project a contemporary lens that has been lacking in conversations about Arizona and its tribal communities.

King shares an explanation by the Gila River Indian Community’s tribal historic preservation officer, Barnaby Lewis: “‘Huhugam’ is not the same as the archaeological term ‘Hohokam,’ which is limited by time periods. The archaeological term does not acknowledge our ancient ancestors nor living O’odham, who will become ancestors today and tomorrow. I am O’odham today, I will be Huhugam one day when I perish.”

Medio Completo will be exploring these distinctions while weaving together each component with water, which serves as the crucial connection among the ecological, economic, and cultural fabrics of the desert. Water as a resource and economic structure through the historic canal system will be ever-present in the exhibition, as it is in our modern life.

Vesich eth ve:m will also promote the importance of water in their project beyond its extrinsic value, delving into its cultural and spiritual side. From the significance of a cottontail rabbit’s dependence on water, to monsoon storms and water rights interpreted through projections and performances – the role of water flows through the entire project.

“Hopefully, whatever happens with this event, we can continue and do more projects like this, and continue the narrative,” Gomez says. “Preservation, ownership, and being able to control our narrative” are key components of We Are Still Here, as they relate to the Huhugam, the O’odham, and the artist collective’s individual heritages, as well. The artists agreed they had learned a lot from this process, and are inspired to spread the knowledge gained from the Huhugam Heritage Center and Gila River Indian Community, so that future generations don’t have to learn these lessons from scratch.

King echoes the sentiment: “We’re not talking about a people who lived and disappeared. No, we still live on through our traditions, our cultural and oral history, our practices, our songs and stories – and we share those. That is something we wanted to do with this group – to help them understand the difference.” King concludes, “So again – we are still here. Our tribe lives on, and we continue.”

We Are Still Here

An Immersive Art Experience Celebrating the Huhugam Water Legacy

Saturday, November 16, 6:30 – 8:00 p.m.

Nina Mason Pulliam Rio Salado Audubon Center

riosaladoaudubon.org