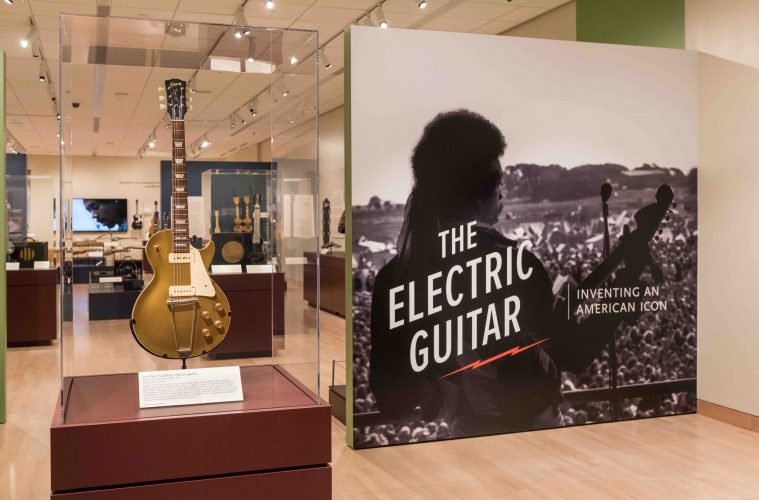

On November 10, the Musical Instrument Museum unveiled its newest exhibit, The Electric Guitar: Inventing an American Icon, with over 80 historic guitars, instruments, amplifiers and original design sketches. While you’ve probably heard some of these very instruments – Pete Townshend’s “5” Les Paul Deluxe, Keith Richard’s Telecaster, and Bo Diddley’s custom “The Get Drum” – visitors have a chance to see the DIY origin story of the first electrically-amplified string instruments unfold before them in their steel and wooden flesh.

The electric guitar so revolutionized popular music it’s hard to remember when horns ruled the roost in the early the 20th century. The first of the exhibit’s three sections displays a number of seminal electrified instruments, inclucing a ukulele, banjo, violin and zither. There is a hand-drawn sketch from Frederick Deardorf, who designed one of the first functioning electronic stringed instruments in the early 1920s, in this case a violin. There are also a number of very early amplifiers, some which look straight out of Edison’s lab and others that appear astonishingly modern for the time.

As the exhibit’s title promises, there are a plethora of guitars from this period, however unrecognizable their designs may be. The first to be electrified were not “Spanish” guitars, those often played while standing with the instrument suspended from a neck strap, but instead lap steel or “Hawaiian” guitars, which are generally laid flat and played while sitting.

“In a few short years, people explored a staggering range of possibilities,” said curator Richard Walter. “It’s just hard to imagine that so much development across so many categories had already been investigated just between 1932 and 1938.”

“In a few short years, people explored a staggering range of possibilities,” said curator Richard Walter. “It’s just hard to imagine that so much development across so many categories had already been investigated just between 1932 and 1938.”

By the late 1930s, the simple yet elegant form of the modern electric guitar began to take shape. George Beauchamp’s refinement of the string-driven electric pickup – the device which converts the physical vibrations of the strings into an electric signal – helped make this possible. After the exhibit opened, Beauchamp’s nephew reached out to Walter, sharing the story of how his uncle’s first model was made with parts cannibalized from the family’s washing machine.

“I thought that was a perfect example of people using what was at hand to develop something totally new, because there were no ready-made parts,” Walter said. “It was kind of the Wild West.”

The exhibit’s second and third section see the electric guitar go from technical oddity to mass-produced commodity and cultural icon, including instruments such as the Elektro A-25, known commonly as the frying pan, which became the first commercially successful electric guitar. It was also first to grace a national radio broadcast in January of 1933. Alvino Rey’s historic performance caused quite a stir, prompting a number of listeners to contact the station to find out what it was they had just heard.

“The electric guitar was a different sound,” Walter said. “Some people thought it sounded almost like an organ and some like a horn. Depending on the recording quality, sometimes it even sounded like a kazoo, that real nasal-but-dense sound.”

“The electric guitar was a different sound,” Walter said. “Some people thought it sounded almost like an organ and some like a horn. Depending on the recording quality, sometimes it even sounded like a kazoo, that real nasal-but-dense sound.”

Rey also helped a number of companies with research and development, all of it together earning him the moniker of, “Father of the Electric Guitar.” It’s no wonder Rey’s historic instrument – with its faded white paint chipping along the edges – is given such pride of place in the exhibit and its marketing.

More than 20 years before Elvis gyrated his guitar and hips into the national consciousness, the instrument was already an emblem for a changing society. As electric guitars became more widely available, they revolutionized popular music, helping usher in first western swing and later rock ‘n’ roll as popular genres.

“Leo Fender in particular was really important because he took the principles of the electric guitar and applied a very smart mass-manufacturing sensibility,” Walter said, pointing out another instrument of particular historical significance in the show. “For all the images of Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton and all the great Stratocaster players, Leo Fender personally wanted to put his fanciest early one in the hands of Eldon Shamblin to play Western swing.”

Whether it was a discordant rendition of the national anthem in the ’60s or the stuccato aggression of punk in the ’70s, the electric guitar has continued to be a totem of youth, rebellion and consumerism. To learn the rest of this story – and find out how the Stratocaster got its horns and the Gibson Les Paul its double humbuckers – you’ll just have to explore the MIM’s exhibit yourself.

Whether it was a discordant rendition of the national anthem in the ’60s or the stuccato aggression of punk in the ’70s, the electric guitar has continued to be a totem of youth, rebellion and consumerism. To learn the rest of this story – and find out how the Stratocaster got its horns and the Gibson Les Paul its double humbuckers – you’ll just have to explore the MIM’s exhibit yourself.

The Electric Guitar: Inventing an American Icon

Through September 15

Musical Instrument Museum

mim.org