Central Yup’ik, Lower Yukon, Alaska. Dance mask, representing the Moon-Woman c.1870. Wood, pigment, vegetal fibers, sinew. Private collection. Photo by Craig Smith.

Once called a “wild beast” for his bold use of color, Henri Matisse continues to influence art and fashion today, more than six decades after his death in 1954. Despite a battle with cancer and other health ailments, to say nothing of the interruption of World War II, Matisse continued to innovate through his final years, working in Vence, an idyllic community in southeast France.

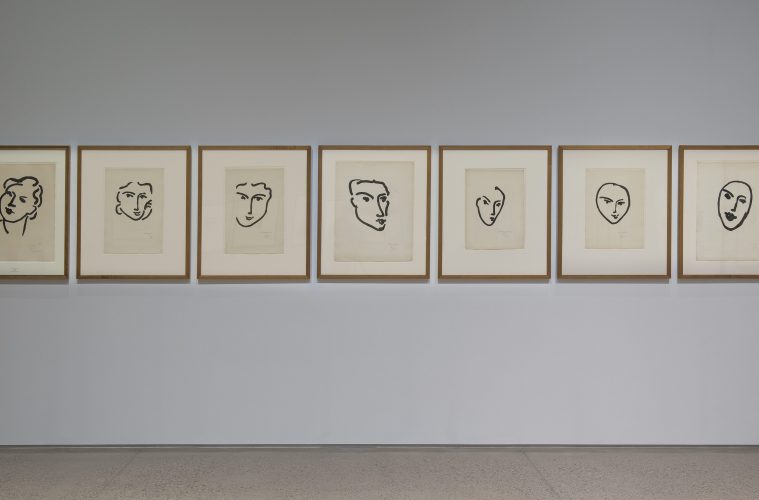

Though his paper cutouts from this period are well known – gracing everything from mass-market products to high fashion couture – his radically simple portraits have received less attention. The exhibit Yua: Henri Matisse and the Inner Arctic Spirit, which opened at the Heard Museum in October and runs until February 3, is changing that.

Henri Matisse, Esquimau. Lithograph, ca. 1947, Plate I (frontispiece) from Georges Duthuit’s Une Fête en Cimmérie, 1963. Collection Musée départemental Matisse, Le Cateau-Cambrésis, France. Gift of Barbara and Claude Duthuit, 2010. # 2010-1-6 (2-1). © 2018 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The exhibit explores not only Matisse’s work but also the art and ideas of indigenous communities that influenced him in his twilight years, especially the Yup’ik people of Alaska. The exhibit features works by Matisse in varying mediums, including nearly fifty drawings based on photographs of Yup’ik and other Northern peoples. These are displayed alongside Yup’ik masks, with a healthy smattering of photographs, films and ephemera woven throughout the exhibition to give context. The show displays items culled from more than a half-dozen collections spread across the world, assembled together for the first (and likely only) time at the Heard for the next few months.

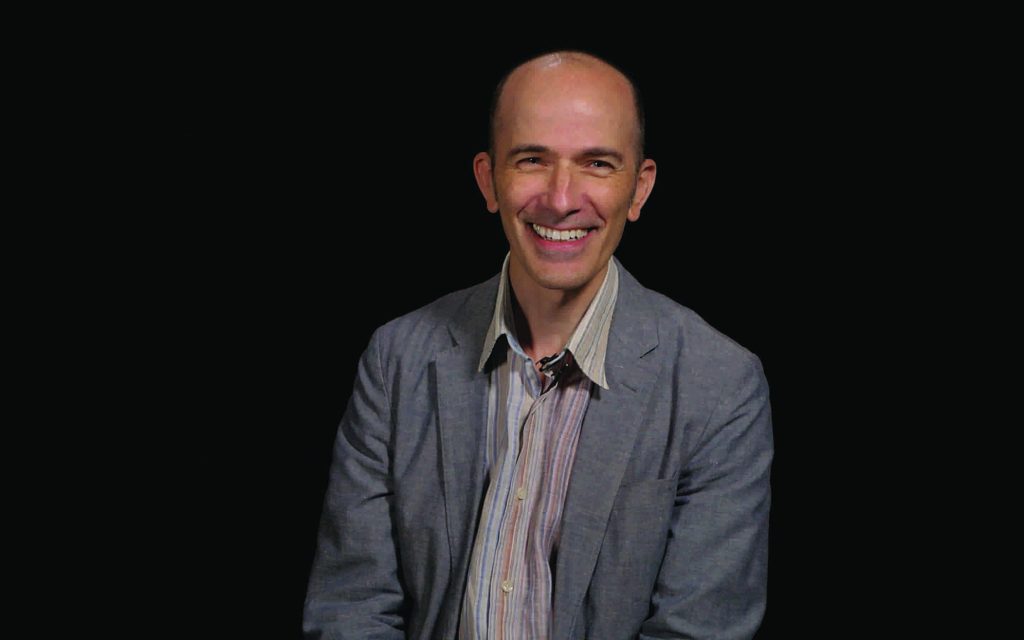

David Roche, director and CEO of the museum, first learned of the connection between the French master and sub-Artic shamans while working for Sotheby’s auction house in New York City in the late ’90s.“As a museum director, I ask myself every day, what are the great stories that need to be told?” Roche said. “When I started at the Heard nearly three years ago, this story was on the top of that list.”

The project has generated new scholarship and insights into both Matisse and the Yup’ik mask makers who were his geographically distant contemporaries. Bringing it all together took years of concerted effort.“This was going to be the most ambitious exhibition that the Heard had ever organized,” Roche said. He forged critical partnerships with Sean Mooney and Chuna McIntyre, the exhibit’s co-curators, along with the many institutions that lent items for use in the show.

McIntyre is a Yup’ik artist, elder and scholar. His linguistic and cultural skills were essential for engaging with the Yup’ik community. By speaking with the descendants of shaman craftsmen in their own language, he learned about the masks, the stories they depict and the stories of those who made them in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The exhibit focuses on the masks of two of these artist-shamans in particular: Ikamrailnguq and Agyatciaq.

“It’s always been a goal to define these pieces not only as works of art but as the personal creations of individuals,” Mooney said. “It is really groundbreaking to look at these masks from that perspective and to be able to (with the help of McIntyre and other Yup’ik people who are familiar with these terms) use Yup’ik language to reconstruct their meaning.”

Mooney is an expert in indigenous art and curator for the Edmund Carpenter Collection of Arctic Art at the Menil Collection in Houston. McIntyre and Mooney, who had previously collaborated on other projects, spent two years defining this show’s scope, with Matisse as their starting point.

“We know of the masks in historic collections in museums today almost as an accident of history,” Mooney explained. “It was only as outsiders during the gold rush and when the first missionaries started going to Alaska that these masks were traded and were retained, which eventually led them to museum collections.”

Adam Twitchell was drawn to Alaska by the gold rush in the 1890s. Eventually settling down, he collected the masks between 1902 and 1912. Married to a Yup’ik woman named Qeciq, he was able to gather the masks and observe their use in Napaskiaq, a village in Alaska.

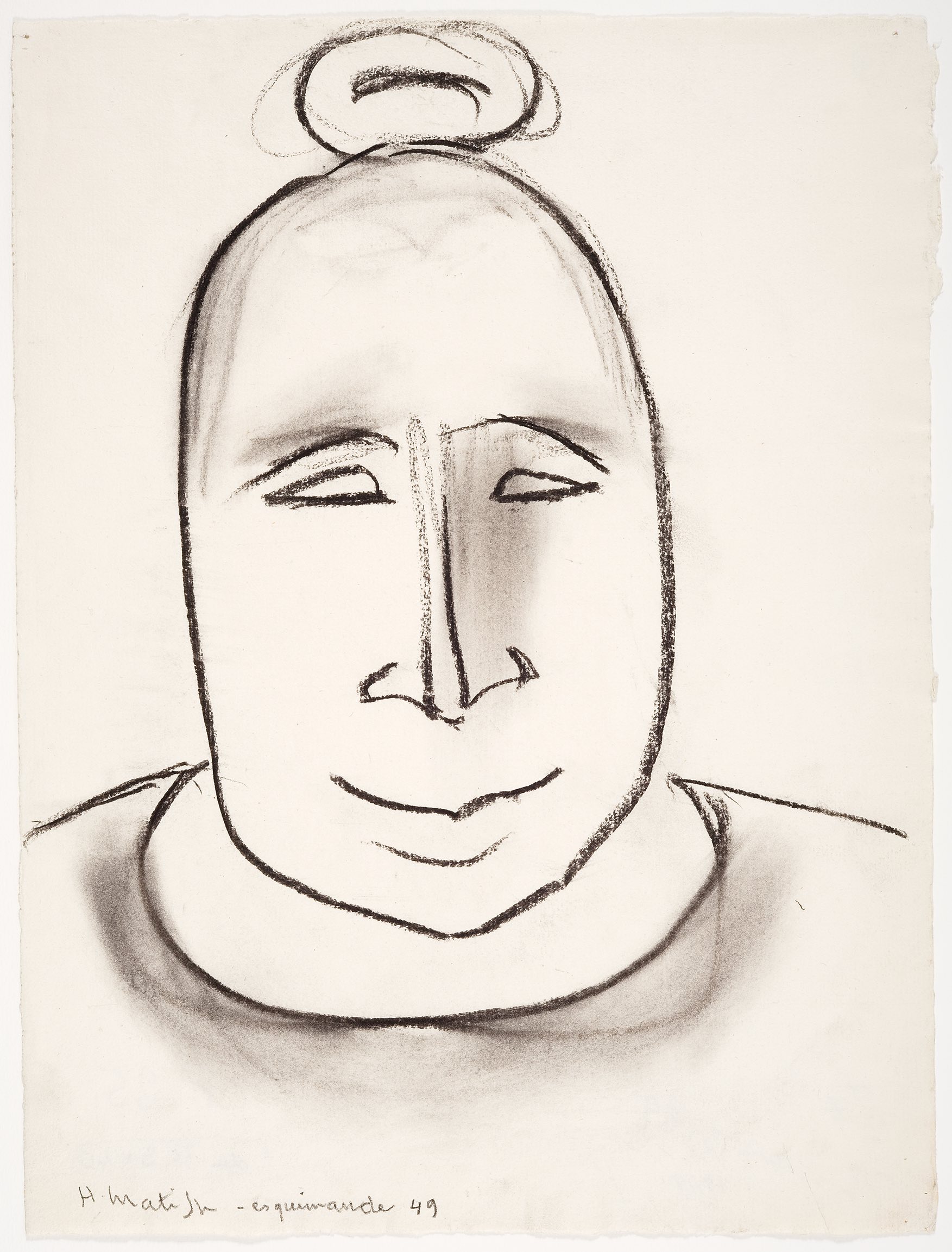

Henri Matisse, Esquimaude. Charcoal on paper, 1949.

Collection Musée départemental Matisse, Le Cateau-Cambrésis, France.

Gift of Barbara and Claude Duthuit, 2010. # 2010-1-9.

© 2018 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Twitchell helped collect and preserve the masks, assisting George Gordon, director of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Anthropology, on a collecting expedition in 1907. Twitchell also corresponded with scholars, such as anthropologist Edward Nelson. It was from these connections that many of the masks on display made their way to New York and then France.“It was a very exciting detective story,” Mooney said.

Georges Duthuit, Matisse’s son-in-law, was in New York City when World War II erupted in 1939. Stranded with other expatriate European artists and intellectuals, they explored vast U.S. collections of Native American art and acquired their own artifacts when possible, including several pieces featured in the Heard show – some of which have returned to the United States for the first time since 1945.

When Duthuit was able to go home following the armistice, he had about a dozen Yup’ik masks with him. Duthuit’s wife, Marguerite, asked her father to contribute drawings to a book inspired by the artifacts that her husband was publishing, titled Une fête en cimmérie. Matisse used photographs of indigenous people from northern latitudes as his models for the drawings.

Central Yup’ik, Napaskiaq Village, Kuskokwim River, Alaska. Aiviqaq yua (Sandhill Crane spirit) dance mask c. 1900. Wood, feathers, pigment, vegetal fibers. Collection of the Fenimore Museum, Thaw Collection, T0651.

Though Matisse did not sketch or copy the masks directly, he drew inspiration from their simple yet elegant lines. He analyzed their visual vocabulary, recognizing the makers as kindred spirits in the quest to distill the essence of a person’s spirit and personality. The influence bled into Matisse’s subconscious and back out into his art. He began calling his portraits “masks.”

The masks that inspired this change in nomenclature were part of a rich tradition of dance, song and story. Yup’ik belief held that such ceremonies ensured balance between humans and the environment in this harsh region. Some of the dances, particularly those occurring in winter, were held in large ceremonial houses called qasgis. The masks were made by the community shaman, angalkuq, and usually represent an animal’s yua, or spirit, as a human face in the animal’s belly.

“They’re always represented with a human face because it’s the personal spirit of that animal,” Mooney said. “The yuais often represented as residing in the belly, like an infant in the womb.”

Mooney and McIntyre carefully studied the motifs represented on the masks, allowing them to understand the main plot points, if not the full stories, depicted in the masks. Outstretched hands are meant to encourage spirits to enter through the mask, though the lack of thumbs ensures they don’t overstay their welcome. A series of concentric rings surrounding a mask is called ellanquaq, which literally translates to “pretend” or “model universe.”

Central Yup’ik, Napaskiaq Village, Kuskokwim River, Alaska. Wanelnguq dance mask c.1900. Wood, feathers, pigment. Collection of the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, 9/3432. Photo by NMAI Photo Services.

“In Yup’ik cosmology, your awareness of your universe, or your existence in that universe, is essential to your wisdom,” Mooney said. “You have all these beautiful concepts that would have been perfectly obvious to a Yup’ik person in a village witnessing a dance or performing a dance.”

Given the double or even triple meanings of the signs, interpretation isn’t always simple. For example, whale flukes can represent labrets, ceremonial body piercings given to elders as a sign of respect. If the flukes are dripping water, they can represent literal flukes of a breaching whale, or the oil being rendered from whale blubber.

“Each mask corresponds to a song verse, and that’s why you see in many cases these related groups or pairs where one complements another,” Mooney explained. “For example, there’s the wolf and the caribou. One is hunter and one is prey. One represents night and the other one represents day. You have these symbiotic relationships between the masks, and that explains a little bit why we were so adamant about restoring the groupings in this presentation.”

At the same time Matisse studied the art and faces of indigenous people, he was undertaking his final masterpiece: the Chapel of the Rosary at Vence. Dedicated to his friend and former nurse Sister Jacques-Marie, Matisse designed every detail of the chapel, from its vivid and colorful stained glass windows to the vestments worn by the priests. The nexus of the two projects, the “mask” portraits and the chapel redesign, is the show’s unifying theme. It is most clearly illustrated by the story of a smile and a fish.

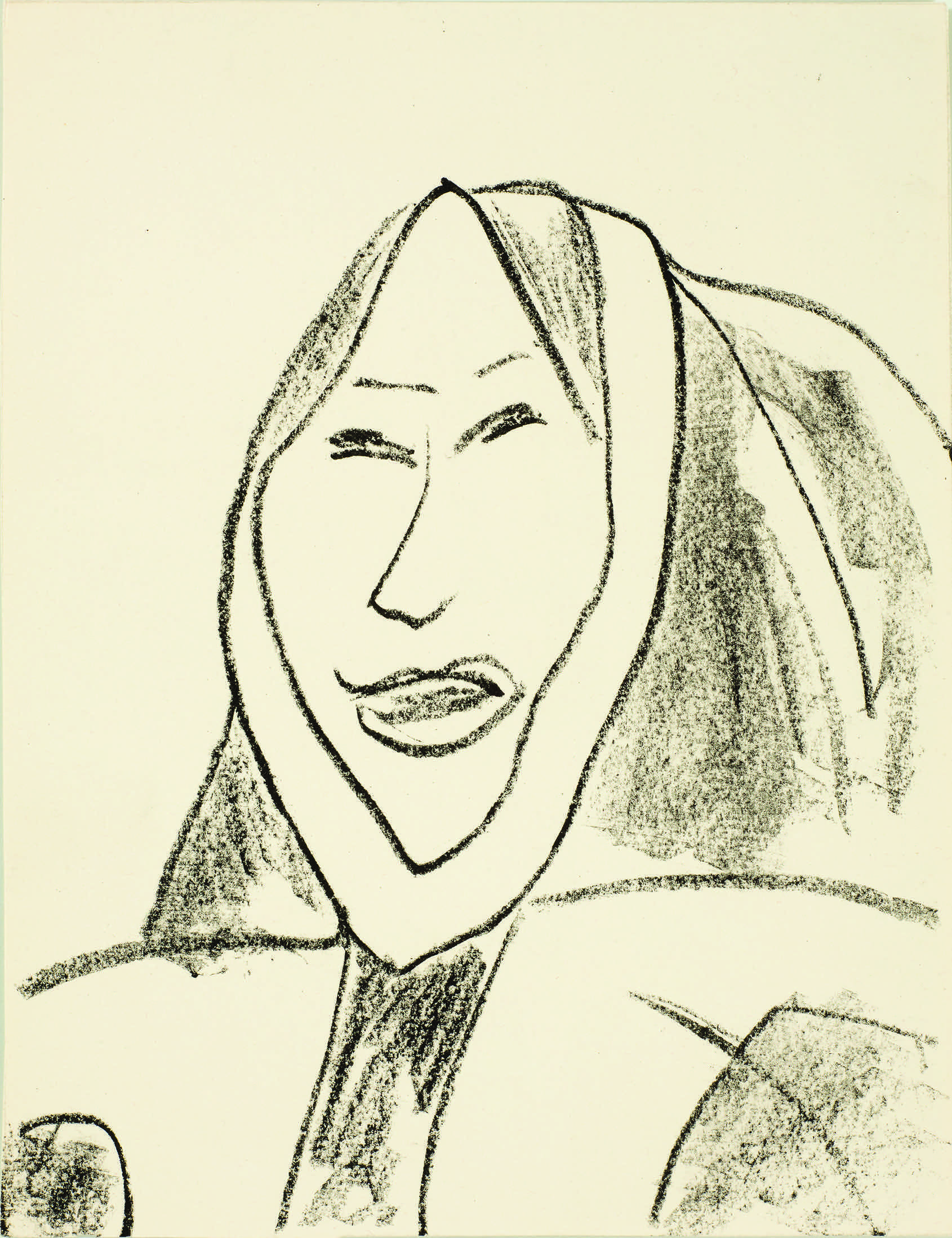

Henri Matisse, Esquimau (after Rasmussen). Lithograph, ca. 1947

Plate XX from Georges Duthuit’s Une Fête en Cimmérie, 1963. Musée départemental Matisse, Le Cateau-Cambrésis, France. Gift of Barbara and Claude Duthuit, 2010. # 2010-1-6 (14-1). © 2018 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

One of the photos that Matisse used as a model was of an elder Yup’ik woman. It was taken on one of Knut Rasmussen’s polar expeditions. The woman’s smile in particular seemed to captivate Matisse, and he drew more versions of her face than any of the others. When Brother Rayssiguier – a church official who worked closely with the artist on the chapel project – dropped in for a chat in April of 1950, Matisse asked him to look at a charcoal sketch of the woman’s smile.

“It looks like a fish,” Rayssiguier recalled Matisse saying. “But I didn’t mean to make a smile that looked like a fish, that would be Surrealism. I made a smile, and it just happens to look like a fish.” Matisse used this smile in the chapel’s main entrance to represent Christ as a fish in front of a net. He hoped it would invoke the smile of the praying faithful.

Matisse continued deftly cutting shapes from gouache-colored paper with almost comically oversized shears until very near his end. Though wheelchair-bound and aged, the wild beast’s claws were not dulled. The Heard’s show shines a fascinating new light on the late work of Matisse and his indigenous counterparts, whose names may have been lost to time were it not for this historic exhibition.