Long before artist Robert Williams founded Juxtapoz magazine, the printed paradise of underground and outside-the-box artwork that debuted in 1994, he was creating bombastic, original artwork that forged the direct pathway to that publication’s birth. Slang Aesthetics! is a touring exhibition featuring a selection of his oil paintings, drawings and immoderate sculptures that is currently viewable at Mesa Contemporary Arts Museum through January 21, 2018.

While Williams and his wife, Suzanne—herself a talented artist—were here earlier this month for the opening reception and related events, tragedy struck back in California. Williams’ dear friend, and a member of the team responsible for the creation and development of Juxtapoz, Greg Escalante passed away at 62. The gregarious and generous gallery owner, collector and longtime supporter of the arts took his own life, after years of battling mental conflict and turbulence. It is a tremendous loss that has leveled the arts community. “It’s such a very sad and unfortunate happening,” said Williams, adding, “The vacuum that he’s going to leave will be huge in the months to come. He was so charitable and organized. He helped so many people, especially young artists.”

The depths of Escalante’s inner turmoil came as a surprise to many, even dear friends like Williams. “He was a very close friend of mine. As I look back, maybe I could have been more sympathetic to him,” said Williams, “but I do come from a nastier world, and at the time, I didn’t realize how emotionally embroiled he was by the devils that continually worked on him.” Escalante was always known for being happy go lucky, but Williams said that he got more of a view of Escalante’s troubles in the very recent weeks before his death.

That “nastier place” Williams himself came from includes what he calls a “very difficult” childhood and teenage years that were loaded with unhappiness. He was thrown out of schools, did jail time and bopped around from job to job. He got a firm understanding of what hard work was and what it meant to succeed and decided to implement that knowledge fiercely when he became an artist. “When I made the decision early in life to be an artist,” he said, “I realized that very few people succeed, and I knew I had to do it.”

He wasn’t entertaining other possibilities as options. “The art community is a very sensitive, caring, delicate world, and I come from a rough, brutal world where the chances of surviving are very tough. I saw the alternatives and I knew I had to make it as an artist.” Even with his view of the art world’s sensitive side, he didn’t kid himself for a minute about the challenges that come with exploring that landscape and hoping for exceptional results. “Everyone can be an artist, but only about three or four percent can be professional artists that make a living at it. It’s a ridiculous percentage—it’s brutal!”

Williams left Albuquerque for art school in Los Angeles in 1963, armed with fantasies of comic book art and pulp magazines and other inspirational imagery, only to land in art school during the heyday of abstract expressionism, where his lean toward bold and imaginative realistic works was stifled. Fluent in art history, Williams understood the why’s of what was being taught at the time, he just didn’t appreciate how abstract work seemed to foster a devaluation of representational art.

“I don’t really favor impressionism and abstract expressionism. I understand the theories and the backbone, and it’s of course legitimate—there’s no bad art—there’s just been a complete denial of representational art.” He sees that changing, now that there are younger generations not being raised on abstract expressionism and conceptualism, but back then, he recalls, “It was omnipresent, it was fucking everywhere, and it was a law.”

He thought pop art might be a pathway toward highlighting the beauty of realistic work, but those hopes didn’t last long. “The problem with pop art,” he says, “is that it is appropriating. It’s not really a free use of the imagination or a way to exercise the imagination. It’s just simply referencing things in your everyday life. If you consider that realistic work, I can’t argue with you, but it’s certainly inhibiting.”

“Inhibited” is certainly not a word that should be included in any description of Williams’ work. He comprehended what was being handed down at art school and honed his skills, but it was different imagery that loaded his mind. “I was attracted to pulp magazines from the 1920s and 1930s, with the licentious, lustful graphics of the woman being attacked by the maniac, that had this specific lighting,” Williams said. “To me, that was real adventurous stuff, and so stimulating, but I was taught that this was not sophisticated. It’s been just in the last 10 to 15 years that I really started examining what in the hell sophistication is.” And? “It’s an inhibition,” he said. “Picasso said it perfectly: ‘The greatest enemy of imagination is sophistication.’ And he was right.”

Out of art school, Williams found himself in a couple of new situations, one being getting hitched to Suzanne, also an art student at the time. The couple has been a team ever since. He also was in the working world, taking some art-related jobs, including art director for a karate magazine, before landing a position with Ed “Big Daddy” Roth, an artist and custom car designer.

This environment felt like home for Williams, who came from a youth steeped in hotrod culture. “When I came to California,” he said, “I gave up on hotrods and wanted to be a young, urbane sophisticated man and get rid of hotrods and motorcycles and become a professional artist. Then I find myself right at Ed Roth’s studios as his art director, making a lot of money.” The fit was undeniable. “I fit in so well, and I knew so much about hotrods and the culture, I just really started weighing the worth of art.”

He was still working on his paintings at night, sold some to a wealthy appreciator, and began to see a demand. “I couldn’t get these paintings shown anywhere, and no one in the fine art world would tolerate ’em, but there was a demand. I was getting a lot of money for them, so there was a real obvious contradiction going on.”

While he was working with Roth, Williams met San Francisco psychedelic poster artists Rick Griffin and Victor Moscoso, who later went on to do Zap Comix in the late ’60s, which Williams got involved with. He loved comic books, and these artists, including R. Crumb, Spain Rodriguez and S. Clay Wilson, faced some of the same challenges he did with producing brash and realistic work in an art world that might not have initially appreciated them.

Not waiting for an engraved invitation, they all forged forward, and Zap Comix revolutionized the comic world. Counter-culture to the max, plump with great art from this treasure trove of artists, Zap fearlessly depicted the underbelly of humanity with brains, humor and frankness. “Zap,” said Williams, “started a whole slew of underground comics in the ’60s and ’70s. It was very influential and changed American culture.”

Punk rock was another movement happy to fly the finger in the face of all that was staid and afraid during its early days. For Williams, it was a chance to connect with other iconoclastic artists. “I’d go to punk rock clubs and afterhours clubs,” he said, “and they’d have these art shows, and the work was so brutal and salacious and nasty that I thought, ‘Gosh, this is a real deviation from academic art, and if I sloppied up my work a bit, I could join these guys.’”

He found excitement in discovering a peer group of painters and was thrilled to make lurid work where he said he had “absolute social and psychic freedom.” He challenged himself to take it as far as he could go. “It was like, ‘How wild can you get?!’ and ‘What happens if you pull out all the stops?’” He did his Zombie Mystery series and couldn’t sell them fast enough. Things really spiraled from there. Williams’ following continued to expand, attracting innumerable fans and collectors. The “lowbrow” tag—echoed in the title of his book The Lowbrow Art of Robert Williams—stuck with the movement he created, which eventually splintered off into different arenas, like pop surrealism. Williams understands that with the growth of any movement comes the need to create more and deeper definitions, but to him, it’s all feral art. “It’s just feral art—art that has raised itself—raised out of the wilderness.”

He started showing with New York’s Tony Shafrazi in 1992, and then Juxtapoz happened not long after that. Williams had previously helped create Art Alternatives magazine, which was successful but went south after the publishing company fired the woman who was instrumental in getting that project going. After Williams had tried some different publishers, Escalante suggested he talk to High Speed Productions, who publishes Thrasher, which often featured Williams’ art. That was a go, and Juxtapoz has gone on to outsell all the biggies, like Art Forum, Art News and Art in America. It also fulfilled Williams’ vision of putting the spotlight on the work itself, not the text.

Williams said he didn’t think it would sustain as long as it has. “We thought we’d never be anything other than an alternative fanzine, but the fact it’s still going strong proves there was a desperate need for this magazine.”

There’s so much to know about Robert Williams. His history is rich. He’s working on his eleventh book. His imagination is boundless. But, truly, the best thing you can do is to get to this exhibition and completely lose yourself in it. That’s what the artist would like you to do. Slang Aesthetics! debuted in Los Angeles in 2015 and will be making its way to the LSU Museum in Baton Rouge after its stint in Mesa.

When asked what he hopes absorption in his work will bring viewers, he said, “I hope that I am bringing out in a person their investigative skills. In other words, I’m not so much interested in if a person likes the painting as much as if they’re interested in investigating it. Investigating it exercises their imagination. If they do that, then they’re gonna want to see the next one and so on. And if I can get them to go to three or four paintings, I know they’ll start liking the paintings.”

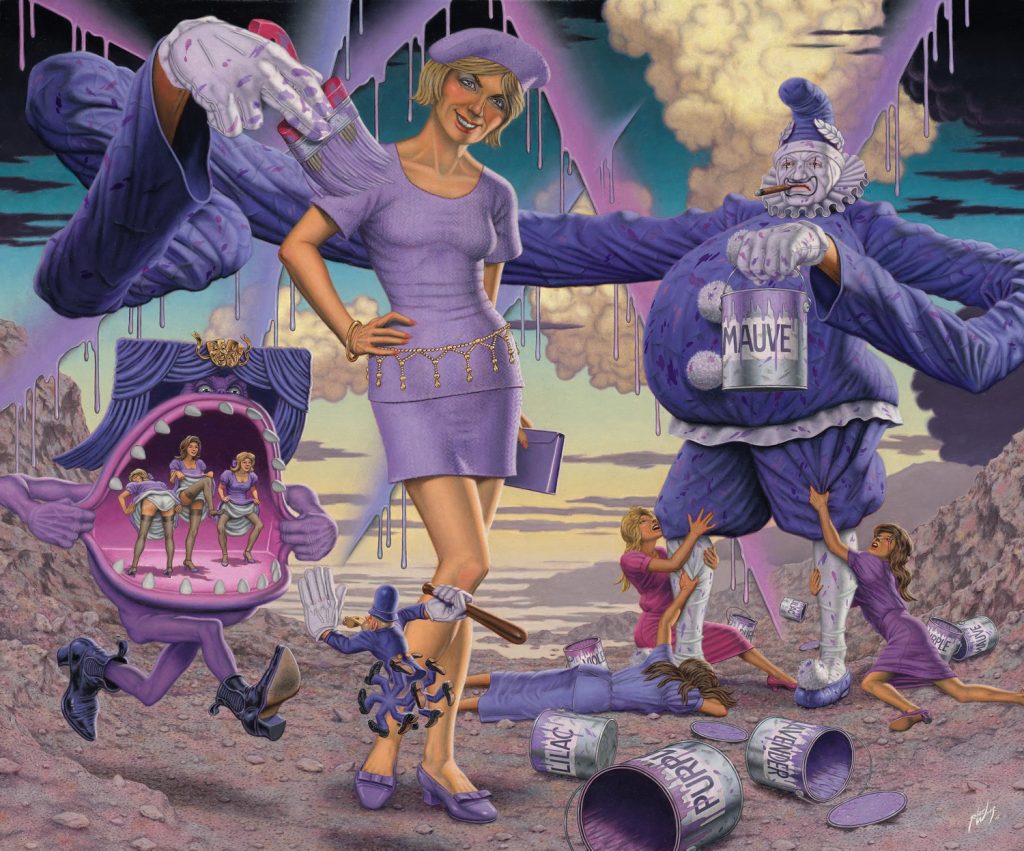

Welcome to Robert Williams’ world. What is not to like? From the electrifying, brilliant colors in pieces like “Fast Food Purgatory” to the dominant purple palette in “Purple As An Explicable Poetic Force,” his mastery of color is enough to bowl you over. His subjects, ranging from sultry to outlandish to nightmare inspiring, are sincere, vivid and believable. The subject matter ranges from hilarious to insightful, provocative and gloriously wild, sometimes—oftentimes—all at once.

As magnificent as it is to be in rooms that have you surrounded by Williams’ paintings and drawings, his fiberglass sculptural work is nothing short of incredible. Flawless and creative, they are 3D manifestations of the artist’s wickedly divine imagination. And, according to him, a hell of a lot of work.

One features 196 impeccably shiny teeth that Williams hand-carved himself. He loves the results but doesn’t know if there will be many more like this in the future. He said, with a laugh, “I’m an old man now, and I just stick with painting, unless some wealthy person comes up and says they’d like to underwrite sculptural work. I’d tackle that in a heartbeat. Those things are so problematic to exist, so the next time you see them, appreciate the hell out of ’em, okay?”

He’s thrilled to be showing here in Mesa and is appreciative of the curators “sticking their necks out for me.” He’s continuing to paint constantly and says his imagination is incontinent. “I wish I had three lifetimes to empty my basket, but for now, I’m pecking away all the time.”

Images:

Robert Williams with his sculpture Rapacious

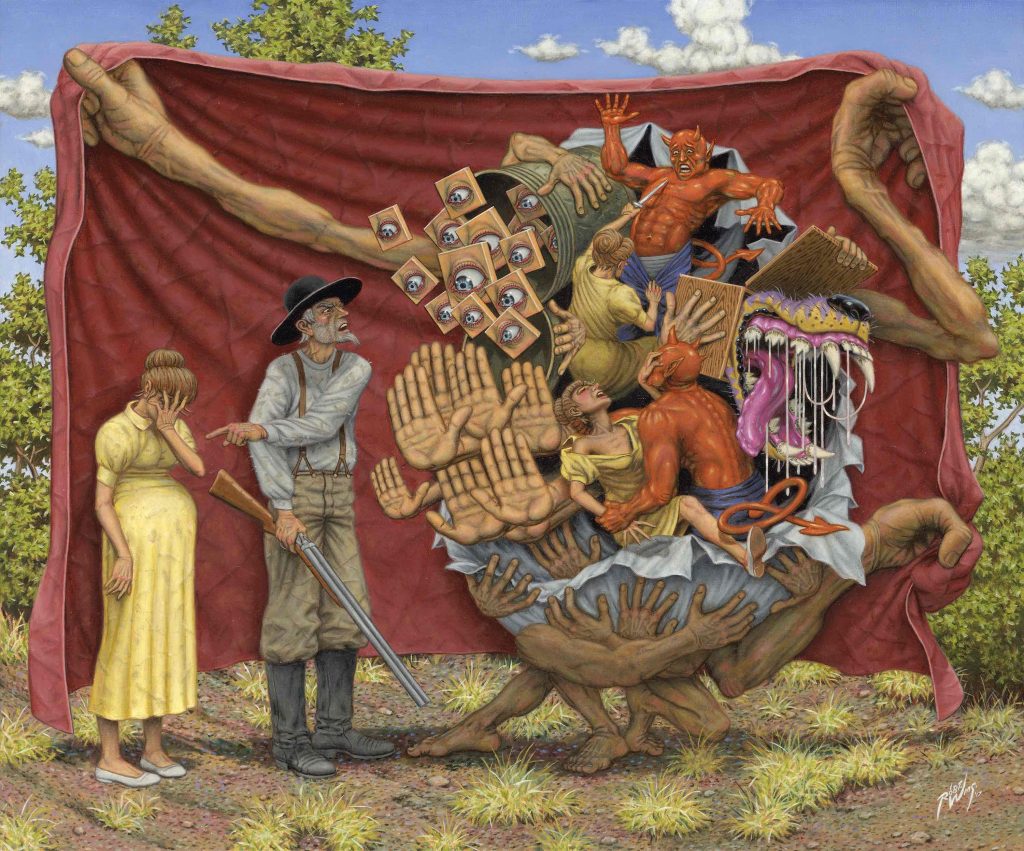

Veil of Paternity, 2017, Oil on canvas, 33 X 29 inches

Purple as an Inexplicable Poetic Force, 2015, Oil on canvas, 30 X 36 inches

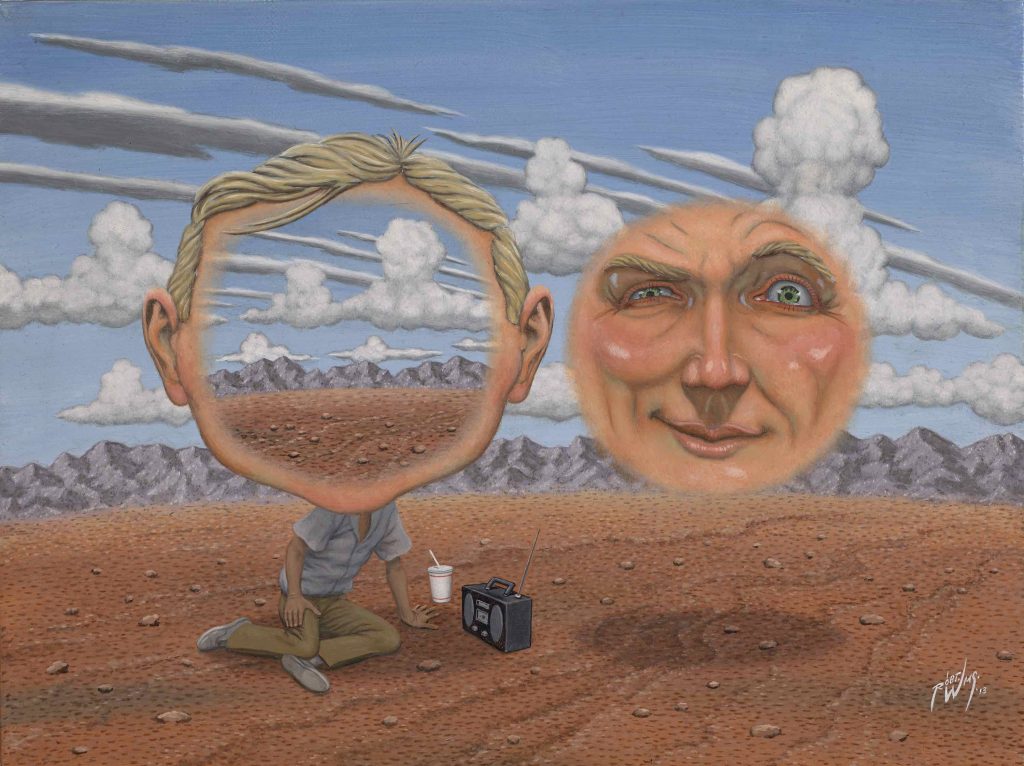

Terra Facia, the Exaggerated Persona of a Poetic Location, 2013, Oil on canvas, 24 X 28 inches

Puppets Orchestrating Puppets, 2013, Oil on canvas, 42 X 42 inches