When Restaurant Progress opened a couple of years ago in the Melrose neighborhood of central Phoenix, this hip, chef-driven concept quickly met with rave reviews, partially due to its ambiance and aesthetic appeal. As they say, the devil is in the details. The talent behind the lovely and well-crafted plates, bowls, and other ceramic tableware, Miro Chun, owner and designer of ceramics company Miro Made This (MMT), pays close attention to detail – almost to the point of obsession.

When Restaurant Progress opened a couple of years ago in the Melrose neighborhood of central Phoenix, this hip, chef-driven concept quickly met with rave reviews, partially due to its ambiance and aesthetic appeal. As they say, the devil is in the details. The talent behind the lovely and well-crafted plates, bowls, and other ceramic tableware, Miro Chun, owner and designer of ceramics company Miro Made This (MMT), pays close attention to detail – almost to the point of obsession.

Being detail oriented is the thing that keeps her going, but sometimes at a slower rate than other ceramicists. “My biggest thing is issues with perfectionism,” she says. “I had to learn to be okay with whatever happens. There’s so much heat and movement inside the kiln. There are like fifty little steps [in ceramics making], with plenty of chances for things to go wrong!”

Ceramics artists tend to be methodical, and for good reason. There is a process that must be followed in order to get the best results from the clay body. Timing must be perfect for drying, the kiln maintained at the right temperature for firing. Almost everything comes down to ritual.

But within that ritual, there is always room for variance. “Having a structure lets me do things like play with the form a little bit, or play with colors, and still have things work together cohesively. Natural systems are very much like that. There is always a structure. We may not see it, but it does help to lend order,” Miro says.

But within that ritual, there is always room for variance. “Having a structure lets me do things like play with the form a little bit, or play with colors, and still have things work together cohesively. Natural systems are very much like that. There is always a structure. We may not see it, but it does help to lend order,” Miro says.

Chun and her husband have an extensive backyard garden where they grow lots of edibles, including some exotics. “Living pretty closely tied to the land, you have to be able to see the smaller things – observe them – in order to tell when things are ripe or ready, or if they need to shift. I feel like it’s the same thing with clay,” she says. Minute changes can occur depending on temperature or humidity. At times it can be frustrating to face an unexpected outcome. But more and more in her practice, Miro says she tries to embrace the unexpected.

Chun came to working in ceramics and porcelain after a career in architecture. She grew up in the suburbs of Philadelphia and attended school in Pittsburgh. From there, she went to live and work in Portland, Oregon, for two and a half years, and then Seattle, Washington, for another couple of years. Her husband is from the Valley, so thirteen years ago, they moved back.

Chun came to working in ceramics and porcelain after a career in architecture. She grew up in the suburbs of Philadelphia and attended school in Pittsburgh. From there, she went to live and work in Portland, Oregon, for two and a half years, and then Seattle, Washington, for another couple of years. Her husband is from the Valley, so thirteen years ago, they moved back.

Chun’s husband is an architect and a landscape architect. “When the permaculture guild was active, he taught some classes for them, and he’s also done some workshops, such as fruit tree pruning, at the Arizona Botanical Gardens,” she says.

Before she really got into her serious ceramics practice, Miro first took a class in Portland. “I was looking for something a little more immediate, because architecture can be so long term with the projects,” she says. At first, she couldn’t get the hang of centering, so she dropped it. Still, her imagination lingered on clay.

“My husband doesn’t remember it this way,” she says, “but I was dreading moving to Phoenix. And as sort of a bribe, he said he would pay for my classes if I stopped complaining.” So after a ten-year lapse, Chun returned to the pottery wheel for another spin. “At that point, I was a little more mature, and a little more stubborn, probably. You know, to just work through it.”

“My husband doesn’t remember it this way,” she says, “but I was dreading moving to Phoenix. And as sort of a bribe, he said he would pay for my classes if I stopped complaining.” So after a ten-year lapse, Chun returned to the pottery wheel for another spin. “At that point, I was a little more mature, and a little more stubborn, probably. You know, to just work through it.”

She began taking night classes at Phoenix College. She says she really enjoyed the tactile nature of being able to create things with her hands. It was a change from architecture, where everything is so digital these days, she says. Around that time she was also working at Lux as a baker. She compares the process of kneading and working with dough to ceramics. The materials are soft and malleable, and it’s necessary to dig right in with the fingers and press with the palms to work. “Architecture is more about hard materials that you manipulate into structures,” she says.

Her friends and family pushed her to stick with the craft. And she’s glad they did. Miro now creates her ceramics pieces full-time. She is such a perfectionist that without their nudging, she might have waited another ten years before becoming a professional ceramics artist.

Her friends and family pushed her to stick with the craft. And she’s glad they did. Miro now creates her ceramics pieces full-time. She is such a perfectionist that without their nudging, she might have waited another ten years before becoming a professional ceramics artist.

Chun does all the throwing, shaping, smoothing, glazing, and firing herself by hand; she doesn’t currently have an assistant – just one friend who occasionally helps out with the shipping and packing. People have been gradually collecting her work, often piecemeal. Fine ceramics can become very pricey to collect, she explains.

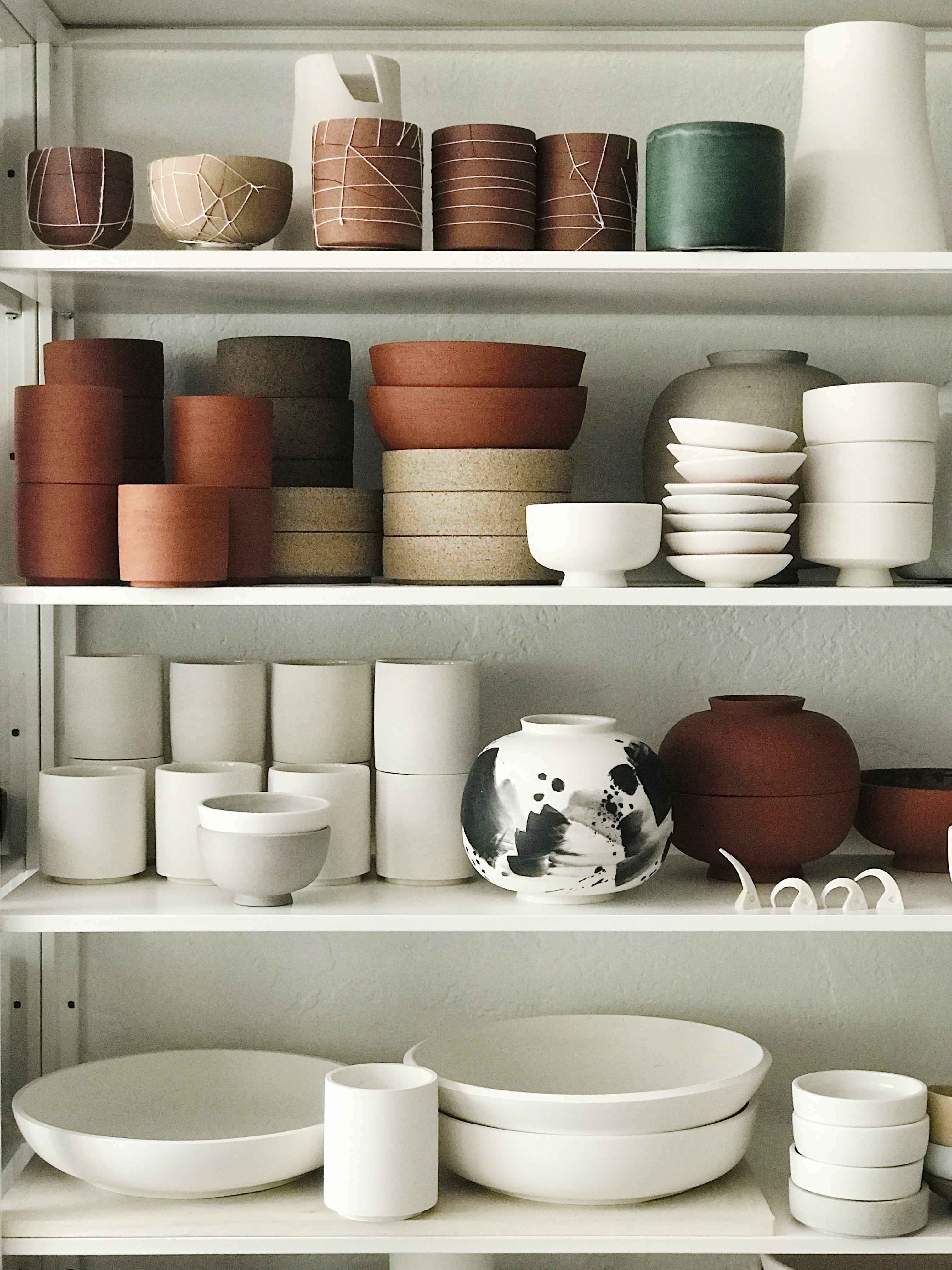

Another factor that sometimes slows the process of creation is that Miro likes to work with a variety of clay bodies. Between each batch that she throws, she has to clean down all of her equipment. The process can be so intense, and clay can get so messy or mix so much, that she keeps two different studios – one for throwing light-colored clays and porcelain, and the other for the reds and other dark colors.

As a result of Chun’s meticulous nature, some of her orders are backlogged. “At this time, people just expect that they are going to have to wait,” she says. “At times, one large order could take up to a year.”

As a result of Chun’s meticulous nature, some of her orders are backlogged. “At this time, people just expect that they are going to have to wait,” she says. “At times, one large order could take up to a year.”

Chun’s first big commission was a large order of planters – around forty pieces in brown, red, gray, and porcelain – for the General Assembly co-working space in San Francisco. The design team working on the interior ordered the planters for the workspace tables.

“Some forms are harder than others, but it’s really just a ruler and the motions,” she says. “It’s kinetic memory. Sometimes it’s about switching clay bodies, too. Porcelain,” she says, “throws like butter.” But it also tends to not be as forgiving if the artist plays with it too much.

When Chun looked at most of the ceramics available, she noticed that she would sometimes only see a small ring of the natural clay on the underside. The rest is usually completely covered by glaze. Miro likes to leave many of the surfaces of her ceramic work unglazed. The main reason is her strong appreciation for the look and feel of the raw clay when fired. There is something extremely honest about the materiality.

Perhaps because of her architectural background, Miro appreciates materials in their pure form and chooses to leave her clay pieces uncoated and porcelains unsmoothed. “Things will smooth out over time,” she says. Of pieces she made seven to ten years ago, she says, “Little bits of sand or aggregate will fall off or wear out.”

Perhaps because of her architectural background, Miro appreciates materials in their pure form and chooses to leave her clay pieces uncoated and porcelains unsmoothed. “Things will smooth out over time,” she says. Of pieces she made seven to ten years ago, she says, “Little bits of sand or aggregate will fall off or wear out.”

“When I went to school, you could see where the students before me had stepped on the stairs,” she says. She admires the marks that people leave behind. This reminder of those who came before adds a nice patina to an object or a place as it ages. “I think the things we value the most are not shiny and brand new. They are the things that have a history, or a memory that has been passed down.”

Over time, MMT serving pieces may collect stains from tea, beets, turmeric, and other richly colored foods. She tells clients if they don’t want to get stains to keep those brightly colored items away from their unglazed pieces.

Many ceramicists sand porcelain smooth, but not Miro. “When it fires and vitrifies, the water leaves, so you will have a tiny bit of that texture,” she explains. “I try not to do as much porcelain in the summertime, because it does dry really fast. And ceramics is all about drying things evenly,” she says. “When it’s hot and dry here, it creates more tension as some parts dry out before others. I usually end up covering and uncovering things a lot to try to keep them even.”

Her ceramics studio for light-colored material is located in a house on a large lot that gets flood irrigation to feed the lawn and an assortment of fruit trees and vegetation. This extra moisture in the atmosphere can really help with the curing process.

Her ceramics studio for light-colored material is located in a house on a large lot that gets flood irrigation to feed the lawn and an assortment of fruit trees and vegetation. This extra moisture in the atmosphere can really help with the curing process.

Chun has been working on some newer, experimental pieces, with an interesting nod to history. She’s taken inspiration from ancient Korean moon jars – throwing two separate hemispherical pieces, a top and a bottom, and then joining them in the middle to create a round, moon-shaped vessel. She likes to collaborate with her mother, a painter, who then decorates the vases with expressive marks using glaze.

“Most of my practice is functional ware, but I’ve got these other series that are less functional,” Chun explains while walking between the shelves in her light-color studio. “Really they are based on things that are happening in the process. Sometimes, because I only glaze the interior and not the exterior, the tension – the shrinkage – of the clay body versus the glaze doesn’t always match. Or there is thermal shock, if I open the kiln too early.”

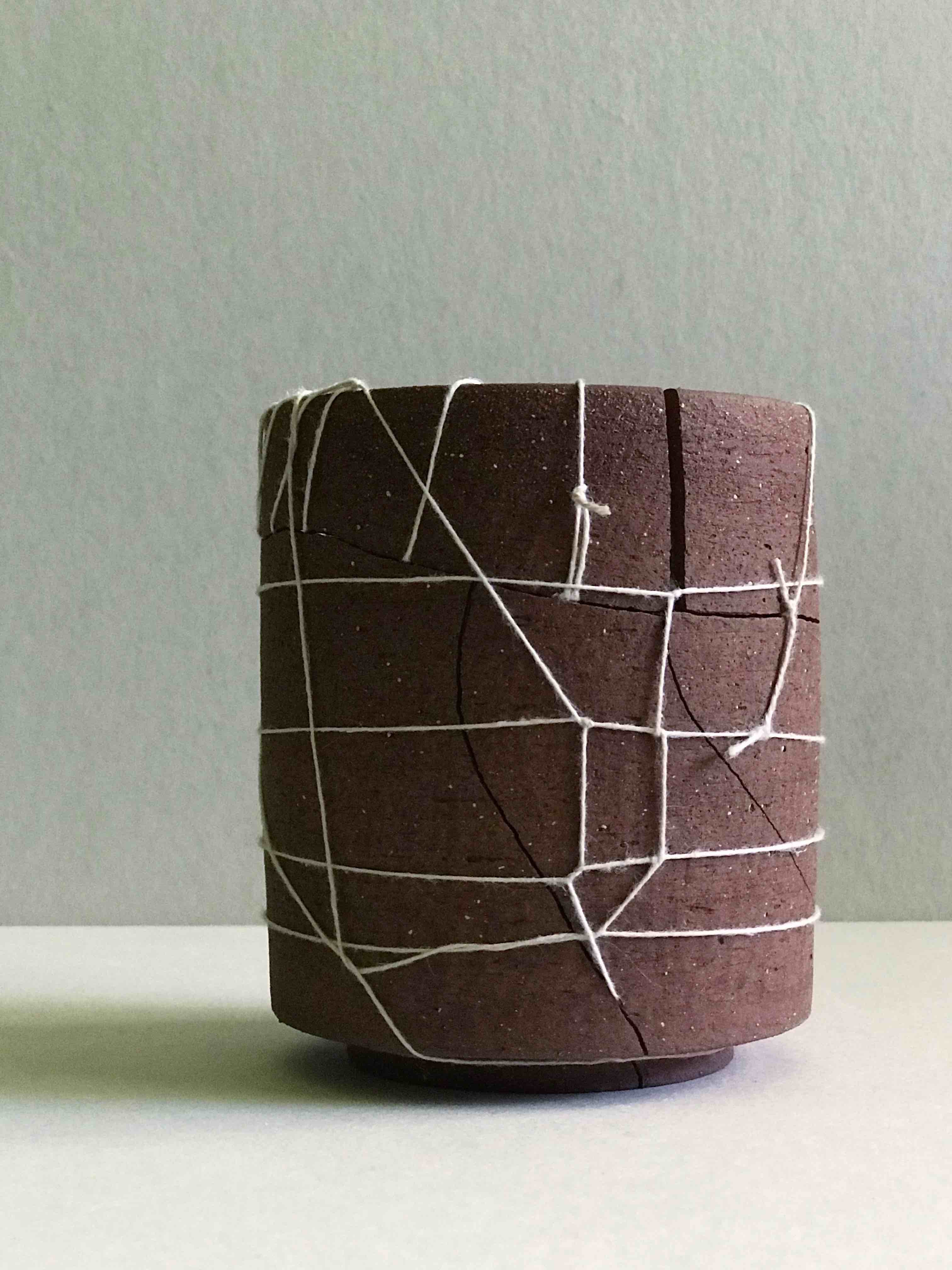

Another series of more experimental pieces comprises those that have shattered in the kiln, which she then mends back together with gold or bookbinding thread. For this practice, she was inspired by the Japanese art of kintsugi, of mending ceramics with gold to fill in the cracks between pieces. She calls this series, “Almost as Good as New.”

Another series of more experimental pieces comprises those that have shattered in the kiln, which she then mends back together with gold or bookbinding thread. For this practice, she was inspired by the Japanese art of kintsugi, of mending ceramics with gold to fill in the cracks between pieces. She calls this series, “Almost as Good as New.”

For the sewn pieces, she guides the needle through the open spaces. She got the ideas and knots from things like trussing (as in tying a roast). “I like connecting to ideas of domesticity and women’s work,” she explains. “This lets me be okay with these things that are not so perfect, and find another value in them.”

It is part of her ethos not to create waste but to find re-uses for things, even when there seem to be mistakes or accidents. Another series, “Perfectly Imperfect,” places value on what otherwise in ceramics making might be considered faults.

Once when Chun was glazing an almost-finished piece, it fell from her tongs. She decided to just continue glazing it and finish it. One of her clients liked the piece and told her that the creative outcome seemed intentional.

“It’s hard to always keep things even,” Miro admits. Some people don’t worry about it, or purposely make things that do not stack. But she likes the challenge. It is this precision that imbues Chun’s work with its Zen-like quality.