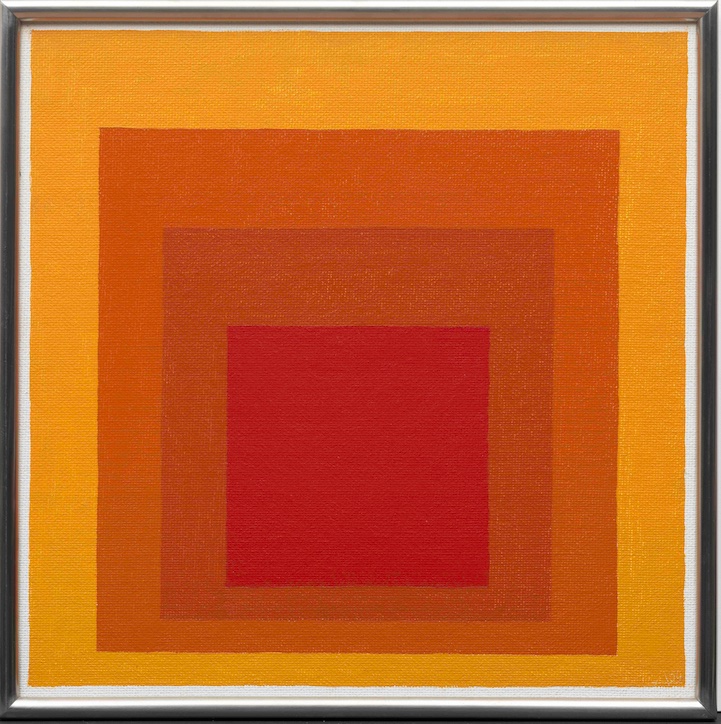

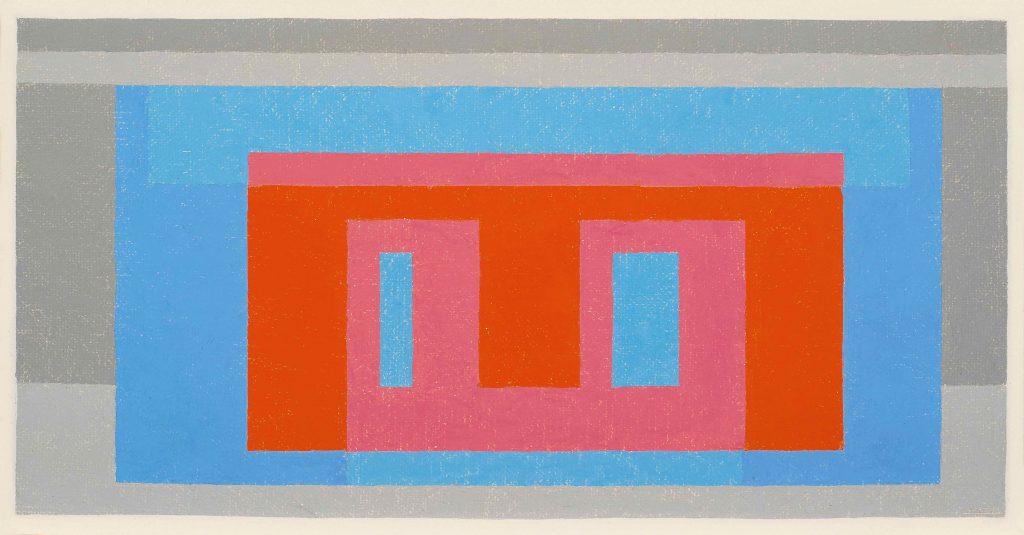

Josef Albers (1888-1976) “Study for Homage to the Square, Closing,” 1964 Acrylic on Masonite, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, The Josef Albers Foundation, Inc., 1996

History can often influence movements in contemporary art, as evidenced by images of the ancients resurfacing in the works of Modern masters.

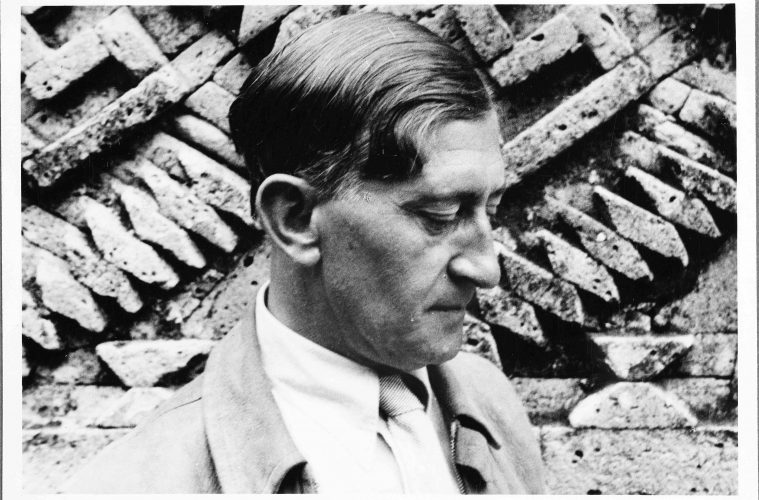

Artistic influences of the past begin to meld with modern artists – Minimalists, Abstract Expressionists, and Bauhaus-era designers – particularly evidenced in the paintings, drawings, and photographs of Josef Albers. “Josef Albers in Mexico” is now on view at Heard Museum.

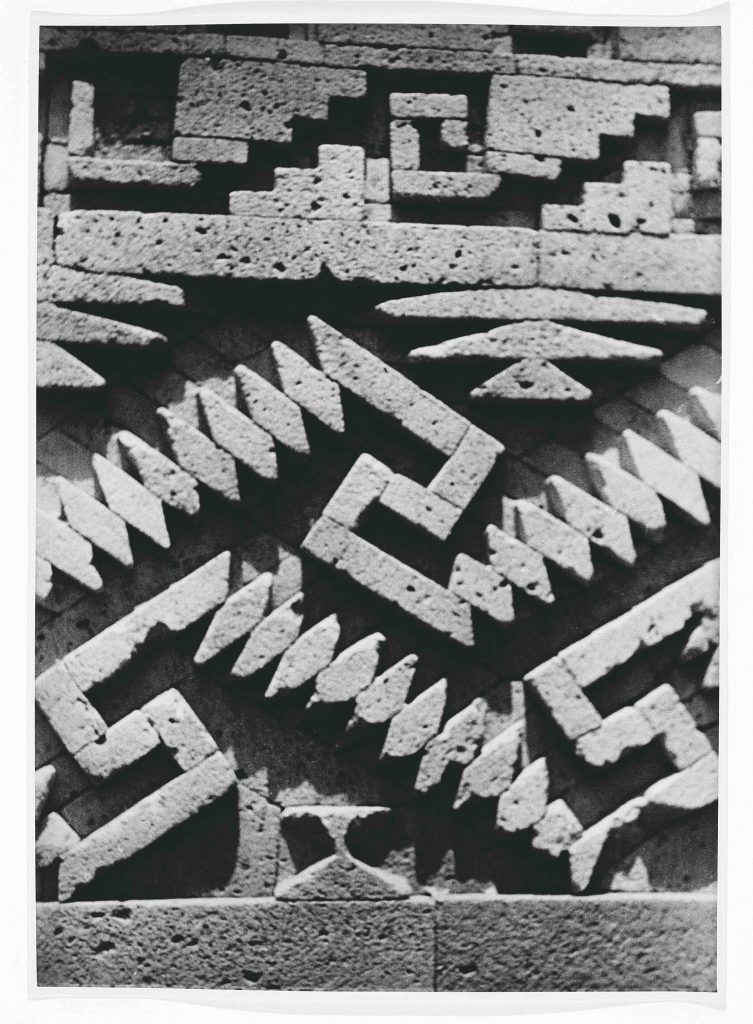

Josef Albers (1888-1976) “Ballcourt at Monte Alban, Mexico,” ca. 1936-37

Gelatin silver print, The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany, Connecticut, 1976

This exhibit allows guests to view and consider the links between Meso-American architecture and ruins that Josef Albers explored during his travels and the way these sites influenced his practice for the next 30 years, explains Lauren Hinkson, Associate Curator of Collections for the Guggenheim Museum in New York, where the show was organized.

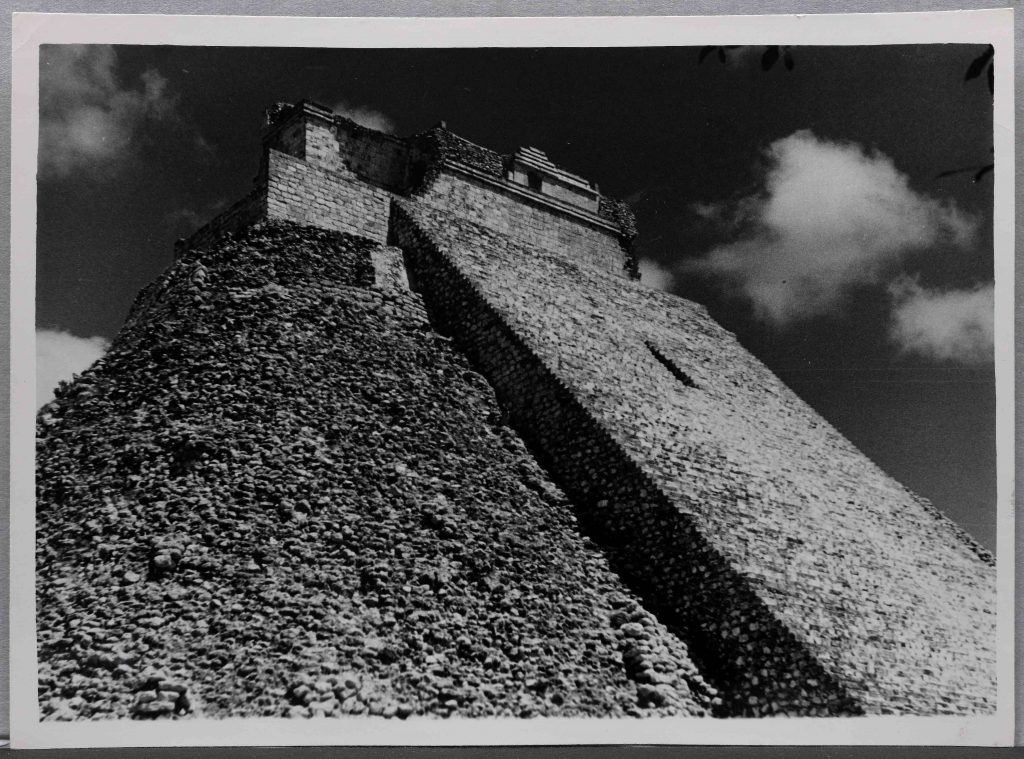

“Before Albers traveled to Mexico in 1935, he was not painting,” Hinkson said. “He took thousands of photos. You can see that he really studied elements of the pyramids and their designs.”

Many revelations come in viewing the photography, Hinkson said. “We have included about sixty photos and photo collages in this show, many of which have not been seen in the United States, and rarely seen at all.”

Josef Albers (1888-1976) “The Pyramid of the Magician, Uxmal,” 1950, Gelatin silver print

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, The Josef Albers Foundation, Inc., 1996

Works in the exhibit are grouped by architectural sites across Central Mexico and the Yucatan peninsula, including Chichén Itza, Mitla, Monte Albán, and Teothuacán. Josef and his wife, Anni Albers, also visited additional sites in South America, including Peru, but the spotlight was placed on Mexico for this show.

“We wanted to focus on both the Guggenheim’s holdings and also what was available from the Albers Foundation,” Hinkson said. Many of the photos came from his namesake foundation. Most of the works, including the very familiar Homage to the Square series, have never been on view in Arizona prior to this show.

Anni Albers was awell-known and influential designer and textile artist. Anni taught design theory to weavers at Bauhaus and later became the school’s acting director. From 1933 to 1949, she was head of the weaving department at Black Mountain College. She was recently recognized with a solo exhibition at the Tate in London from October 2018 to the end of January. She is seen in several of the photos and contact sheet collages.

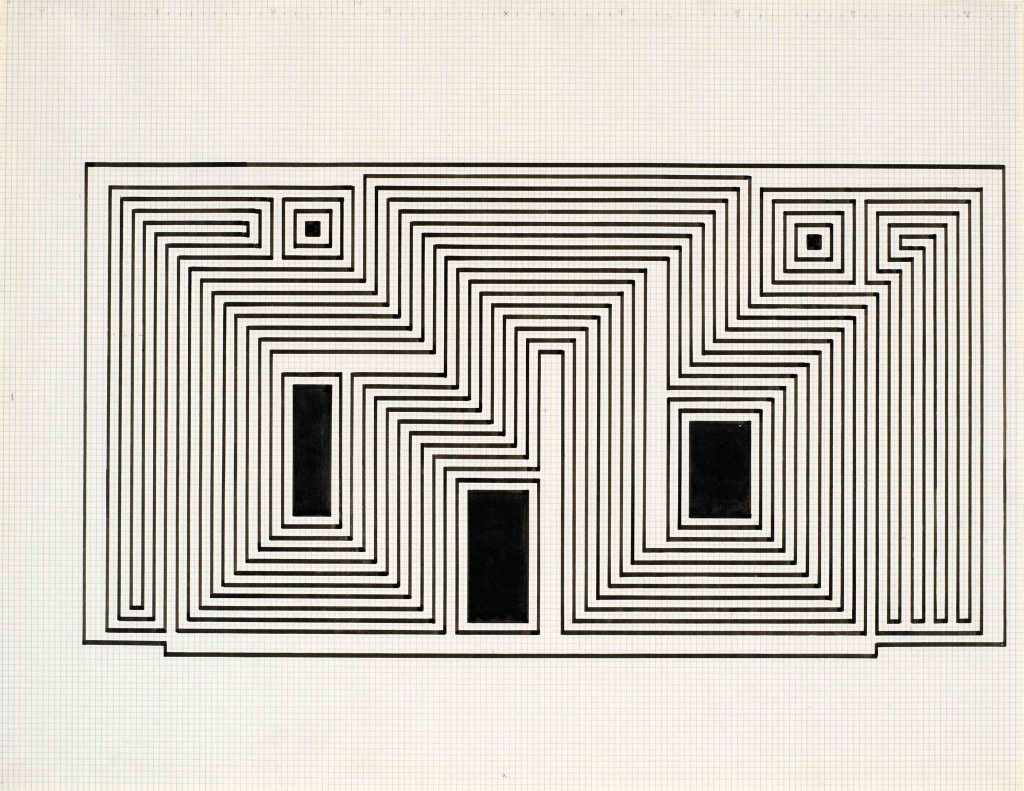

Josef Albers (1888-1976) “Study for Sanctuary,” 1941-1942. Ink on paper, The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany, Connecticut, 1976

Hinkson says she discovered Albers’ photographs in the Guggenheim collection about 10 years ago and became very excited about them because they had not been shown. She connected with chief curator Brenda Danilowitz of the Albers Foundation, then planned and arranged for the collaboration. While much of the work comes from the Guggenheim collection, Hinkson also borrowed extensively from the Albers Foundation to complement, Danilowitz explained.

In the arrangement of this exhibit, the juxtaposition of photos of geometric and serpentine patterns next to the paintings of Albers makes it easy to see the influences in shape, texture, and hue. “He started experimenting using the colors of Mexico,” Danilowitz said, pointing out details of some of his older paintings.

Some credit Albers for inspiring the Minimalist movement in art, and he is often noted for his work in color theory. Though Donald Judd called him the godfather of Minimalism, Albers probably wouldn’t have labeled himself that way, Danilowitz said. However, his teaching at Black Mountain College and Yale directly influenced a generation of artists, including Cy Twombly, Eva Hesse, and Robert Rauschenberg. “All of the ’60s artists knew about Albers. That is when he began to be seen as this old master,” Danilowitz said.

Josef Albers (1888-1976) “Luminous Day,” 1947-1952, Oil on Masonite, The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany, Connecticut, 1976

Albers joined the Bauhaus school of art, design, and architecture in 1920 at age 32. He was one of the first students to become a meister,or master, Hinkson says. Due to pressures from the Nazi government, the school was forced to move from Weimar to Dessau and then Berlin in its final months. Josef, Anni, and many others fled Germany. After relocating to the United States, Albers became active at Black Mountain College in North Carolina and later settled in Connecticut to teach at Yale. He and Anni continued their travels through Mexico into the 1960s.

Over the decades of their travel, the development of the tourism industry in Mexico is also chronicled. “When they first arrived in the 1930s, there wasn’t much,” Hinkson said. “In one of his tiny contact prints, you can see Josef Albers standing in front of a streamlined car, right next to a pyramid, because you could drive right up to the pyramids and walk right in.”

At the Zapotec site, Monte Alban, in the 1940s and 1950s, Mexican archeologist Alfonso Caso was in the process of excavating for years. This was particularly exciting to Josef and Anni because each time they returned, there was something new to see, Hinkson said.

Another interesting part of this exhibit is the collection of a few well-preserved Pemex travel maps. These maps were produced by the state-run oil company to support the travel industry and designed as highly visual souvenirs.

“Josef Albers in Mexico”

Heard Museum

Jacobson Gallery

Through May 27

heard.org