Thirty-eight might not seem quite old enough for a museum retrospective. But in just 38 years, Alaska-born Native artist Nicholas Galanin (Tlingit/Unangan) and has produced work in many different media that doesn’t just “speak volumes”: it sprawls, twists, kicks and screams – in this case, across more than 12,000 square feet of gallery space at Heard Museum.

Dear Listener: Works by Nicholas Galanin is the first contemporary art show at Heard in about a decade focused on the work of one living artist, according to curator Erin Joyce. The show includes some old works, some new and some produced exclusively for the retrospective. In tandem, these pieces create a personal, spiritual and insightful journey through the perceptions and experiences of a political, very mindful, working artist.

Upon entry into the Dennis H. Lyon Family Crossroads Gallery, a transitional space, one may notice muted blue light cascading down from the usually bright skylights. The artist and curator asked Heard Museum to drape the skylights in blue plastic tarps, not just for mood but also to pay tribute to the many uses of this inexpensive resource in Native communities. These tarps are often used to patch leaky roofs, cover damaged car windows and as temporary shelters and sheds. The blue plastic tarps are so ubiquitous, there’s even a nickname for homes made out of them – “tarp-ees.” The blue tarps appear “because they are readily accessible and very inexpensive. A lot of people are living below the poverty line on reservations,” Joyce explains.

SHE IN SKY FORM: NO PIGS IN PARADISE Collaboration with Nep Sidhu Rope, Mongolian Lamb, Cocoa Fiber, Brass Bullet Shells, Cotton Dimensions Vary, 2015

Under the blue light stands the enormous growling head and upper body of a polar bear, shot by a sport hunter in the village of Shishmaref, Alaska, in the ’70s (“We Dreamt Deaf”). The form seems to melt down into a bearskin rug, splayed open, as if across a hunting lodge floor. Just as the polar bear seems to melt away into the floor, the community of Shishmaref is currently melting into the sea due to global warming.

Inside the main gallery, the Virginia G. Piper Charitable Trust Gallery, temporary walls are arranged in a cross shape. “I really wanted to have sort of a cathedral-like feel to the gallery. Thinking about how museums are often quasi-religious spaces anyway, I wanted to play with a form of institutional critique that way,” Joyce says. Some of Galanin’s work references Christianity. Planning of the floors in this area followed the cardinal directions, which helps support a thematic metaphor of cultures colliding or being at a crossroads.

GOD COMPLEX, Glazed porcelain, 72 x 72 x 10 in, 2015 Permanent Collection of Denver Art Museum: Gift from Vicki and Kent Logan to the Collection of the Denver Art Museum, 2017

The main altar displays Galanin’s porcelain sculpture of a police officer’s riot gear (“God Complex”), with helmet dangling and arms spread open, to resemble the body of Christ on the cross. This piece has been featured on the cover of the New York Times.

Before this “altar,” a dialogue naturally arises about the relationship between Native people and law enforcement, which historically has not been peaceful. “Native people are the highest group to be profiled and assaulted by police officers,” Joyce says.

On the north wall is a small apsidal chapel, inviting more comment on the themes of commodification and reclamation. A painting displayed above the altar combines Russian Byzantine imagery with an image from indigenous North America.

“He’s taken a Pantocrator – a blessing, Christ image – probably from Byzantine or medieval [times], and he’s put a Tlingit shaman’s mask over it. Sort of playing with this idea of religion in both contexts and re-appropriating religion after forced missionary actions,” Joyce says.

Beneath this cultural mash-up is a handful of thick, authoritative-looking texts spread open on another altar. The books present “facts” and “truths” about Tlingit culture, but they all were written by Caucasian writers. The artist has hand-cut the profile of his own face into thousands of pages of the volumes. Joyce explains that this is one way of inserting the authentic, real Native American into these texts that were written without permission by those outside of the culture. On the wall above, accompanying the altered books, two busts – arrangements of 1,000 hand-cut pages – splay out from the wall, like faces peering down on the viewer from above (“What Have We Become?”). The artist wants you to see, and he wants you to know. In this respect, many of the works invite Dear Listener into the dialogue.

Along the walls of the inside nave are 13 new monoprints, produced for the show. Theirarrangement echoes the stations of the cross. To the south of this is a well-known piece of Galanin’s, “Arrows Casting Shadows.” From the ceiling hang dozens of ceramic arrow sculptures painted with a Delftware pattern detail. These are from a show of Galanin’s from a few years back where he Europeanized or “white-washed” several Native objects with this pattern, including masks and other tools. From a distance, the shower of arrows produces the visual effect of a cowboys-versus-Indians clash in an old Western. But cast in ceramic, the weapons become fragile – the ultimate oxymoron.

Tucked into the easternmost gallery is a set of avant garde fashion pieces that clearly blend many different cultural and global influences. The “No Pigs in Paradise” series addresses worth and safety for Native American women inside and outside of their communities.

The fashion pieces are the result of collaborative efforts within Galanin’s creative collective, Black Constellation. Members of the collective include Nep Sidhu, a Sikh artist based in Toronto; Maikaiyo Alley-Barnes in Seattle; Ishmael Butler and Tendai “Baba” Maraire from the group Shabazz Palaces; and Otis Calvin. The artists collaborate on these garments, and Shabazz Palaces wears some of them in performance. On Nep Sidhu’s website, Black Constellation is described as a “cross-disciplinary guild of Soothsayers, Makers, Empaths and Channels.” The artists met while participating in a group art show at the Frye Art Museum in Seattle four years ago. Their collaboration extends beyond visual art: Shabazz Palaces are a musical performance group, and Otis Calvin plays with Galanin in their band, Indian Agent (both bands played at Not a Block Party, the show’s opening night at Heard).

Nicholas and his brother, Jerrod Galanin, also collaborate often under the moniker Leonard Getinthecar. In the Heard’s Freeman Gallery, their “Space Invaders,” painted on a deerskin with Nintendo/arcade game space invaders, represents white settlers and their encroachment. Another painting, on seal hide, shows a group of four walruses on a small iceberg. It is well known that indigenous people who hunted walruses and seals were in the habit of letting nothing go to waste, neither tusks nor oil. Yet a looming menace casts its shadow on these blubbery animals in the painting – the dark shadow of an enormous offshore drilling rig. It is yet another sign of the toll of man’s interference with nature, the oil industry encroaching on wild habitats.

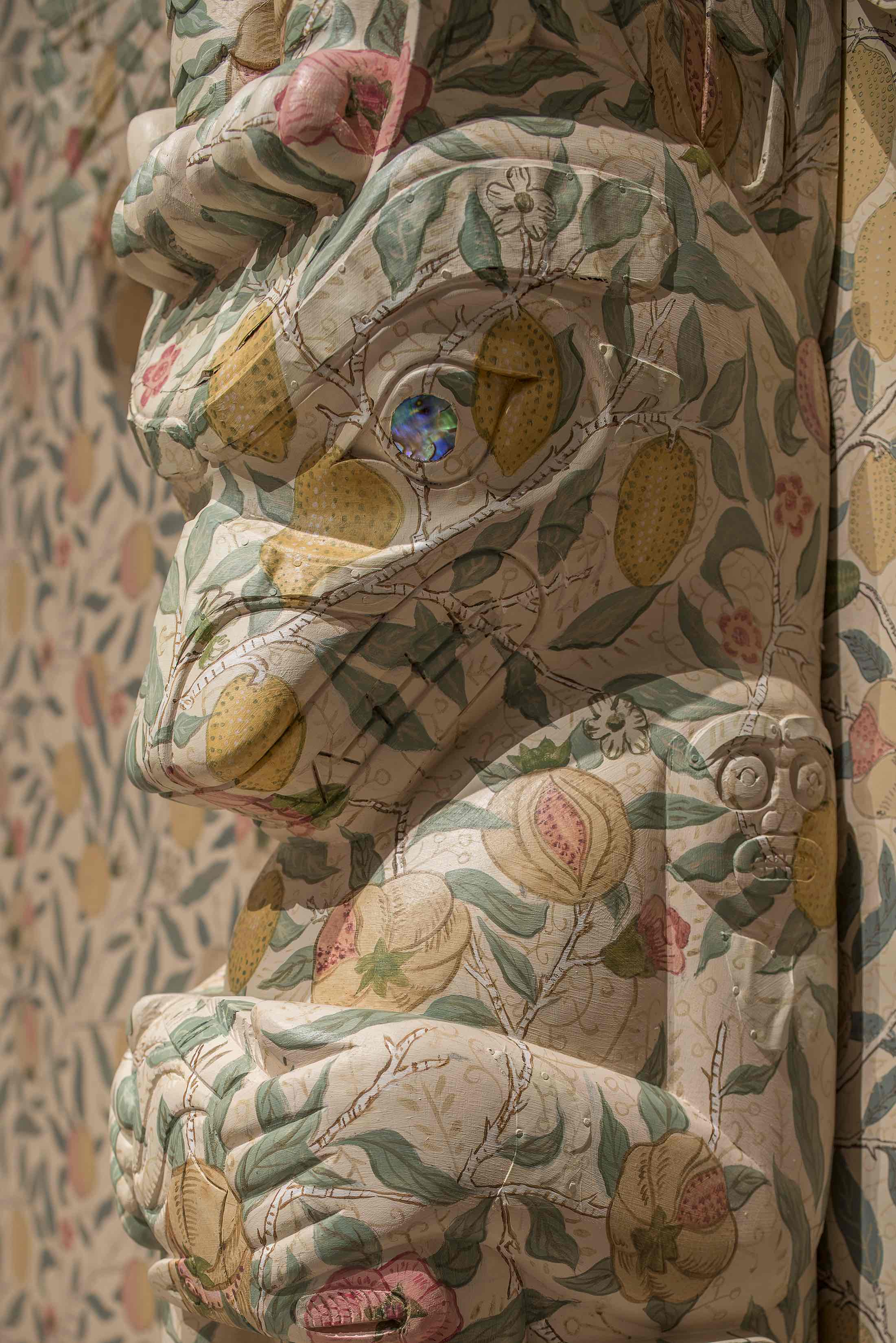

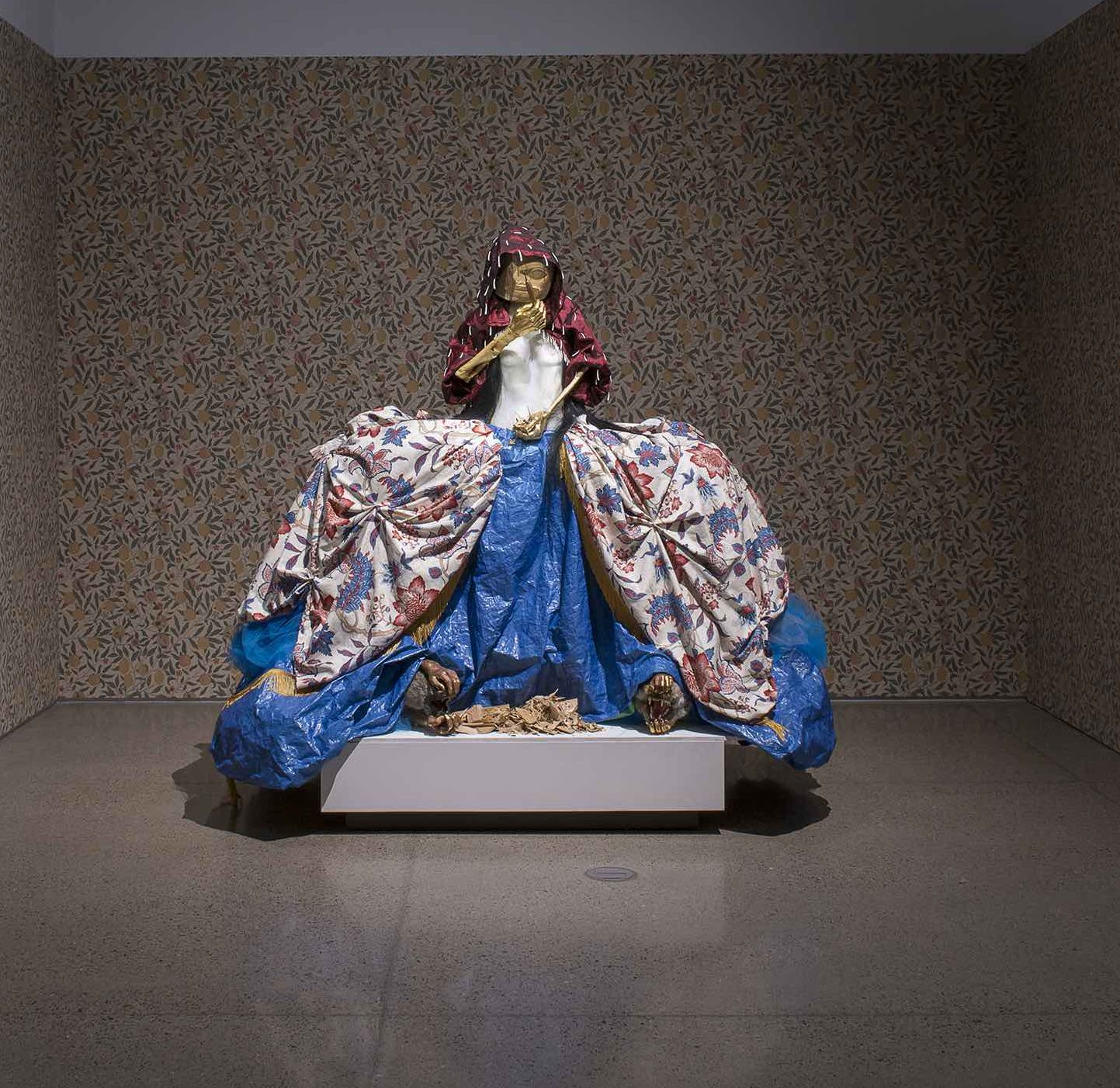

Returning to the front of the house in the Virginia G. Piper Charitable Trust Gallery, a small, temporary room has been set aside and decorated with smooth, flowered wallpaper. The 1866 William Morris–designed pattern and the shape of this space help visitors envision a parlor in an old Victorian home. Here you will find another of the Indonesian knock-off sculptures – this one has been hand-painted by the artist to match the wallpaper identically (“Imaginary Indian: Totem”). The totem is fake and camouflaged well in the middle-class room, save for one distinctly Tlingit trait: its abalone eyes. This totem stands in conversation with another character, a woman made of wood wearing a multicolored, multilayered patterned dress.

This piece, “Creation With Her Children,” is a collaboration with Galanin’s partner, artist Merritt Johnson. A blue plastic tarp peeks out as a layer of the woman’s petticoat. Her children are animals who gather at her feet, beneath the folds of her gown. In one hand she holds a mirror, and in the other she holds a knife, gazing at her reflection while carving her own face “out of necessity.”

CREATION WITH HER CHILDREN Collaboration with Merritt Johnson Plastic Tarp, Fabric, Cord, Wood, Horse Hair, 2017

Additional installments of the “Imaginary Indian” series are on view in the show, deeper into the Freeman Gallery. Photographic images of what look like Native American masks handcrafted in the tradition of people of the Pacific Northwest come from Galanin’s 2015–2016 series “Kill the Indian Save the Man.” But these masks weren’t really made by Native Americans, they were fabricated in Indonesia, probably intended to be sold to tourists. Galanin purchased the masks and then re-appropriated them by using an axe to chip each mask apart; he then glued all the pieces back together in an inside-out arrangement. He also added horsehair to each mask and ceremonialized the process with a dance. Also on view is a video of the process.

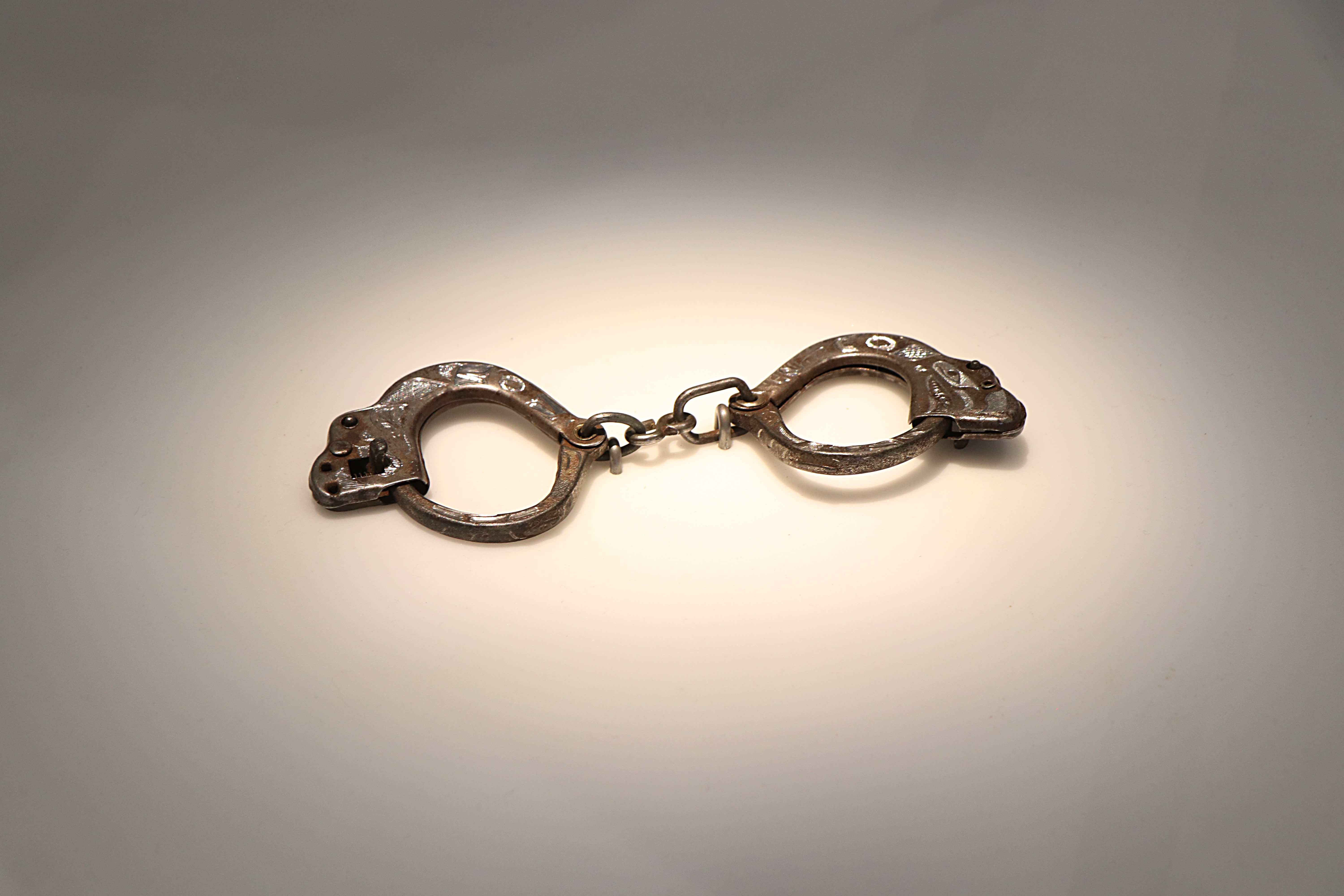

Encased in a large, lonely glass box, but with very intentional spotlights, is a tiny pair of elegantly carved child’s handcuffs (“Indian Children’s Bracelet”). This item is an actual relic from history, something government officials shoved onto the skinny wrists of indigenous children during their forcible removal. In the light of the display case, they glint invitingly, almost like an elegant baroque locket or some other precious object that begs to be stared at. But in this case the stare becomes a gape when one considers how and why this item from history was once utilized.

There are several moments in Galanin’s retrospective show where the startling realities of unfairness, injustice, brutality and outright intolerance break to the surface. Another occurs in the back gallery where two video segments are displayed alongside nine men’s torsos molded from ballistic gel. Ballistic gel is a substance that firearms producers use to test the accuracy and impact of various projectiles. “Supple Plunder” tells the story of Russian soldiers rounding up and then tying together twelve indigenous men in single file, in order to settle a bet: How many men could one bullet kill?

The bullet stopped in the chest of the ninth man.

“The gel torsos are very temperamental. If you touch one, it leaves a fingerprint,” Joyce says. Before opening the show, the museum has to employ a heat gun to smooth out a mark on one of the torsos. The half-bodies are translucent, and it’s easy to track the path of the bullet and find the mark where it stops.

A SUPPLE PLUNDER with Leonard Getinthecar, Ballistic Torsos, Two Channel Video Installation dimensions variable, 2015-2018

During First Friday weekends, some performative pieces will come to life in the Freeman Gallery. For example, in Galanin’s “White Carver” series, documents, a live person and video components speak to the objectification of Native people. For many tourists visiting Alaska and Northwest reservations, a highlight is viewing demonstrations of Native art-making. On these visits, a Native carver or other artist is put on display, almost as if in a zoo. But Galanin has turned the gaze. Instead of an “authentic Native American,” a white man sits in the hot seat, carving what appears to be an important or sacred Native American object. Upon closer examination, the object turns out to be a comedic foil.

The galleries are packed with a wealth of different two-dimensional, video and performance work, fashion collaborations and other forms. For a man not quite four decades old, Nicholas Galanin has been busy as an artist.

This is Joyce’s ninth exhibition curating and working with Galanin. She has also worked with him on shows in New York City, Santa Fe and Flagstaff. She first met him when she interviewed him in London several years ago.

Dear Listener invites guests to be fully present and to unplug our ears. To live in the moment. And to listen.

Dear Listener is on view at Hearn Museum through Sept. 3. Learn more at DearListener.org.