“There’s probably a mine up there.”

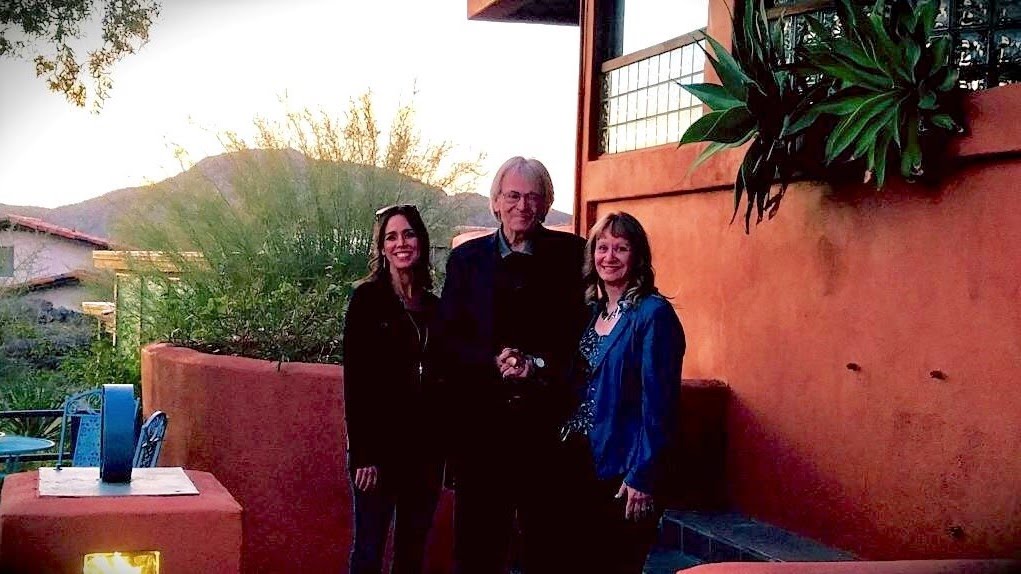

Charles Schiffner and I are standing in the backyard of a house in Sunnyslope. A mountain rises over lemon trees and a wall that runs along the edge of the property. The architect points at a tiny patch of white rock on the mountainside: “That’s quartz. Prospectors searching for gold would start digging whenever they found quartz. Usually if you see one, the other isn’t far away.”

At this distance, the quartz he’s gesturing toward is as small and insubstantial as a tennis shoe hanging from a distant power line. I could have stared at that expanse of rock, dirt and cacti for a half hour and never noticed it, but he saw it in a heartbeat. That eye for detail, his profound awareness of his surroundings, is just one of the many qualities about the man that make him a great architect.

“Architecture is the least understood or comprehended art in America,” Schiffner says ruefully as we sit in the shadow of the mountain. “It usually isn’t until college that you can get a class in architecture. And because there’s so much bad architecture – just drive down Thomas Road if you want to get an image – we’ve become desensitized to it.”

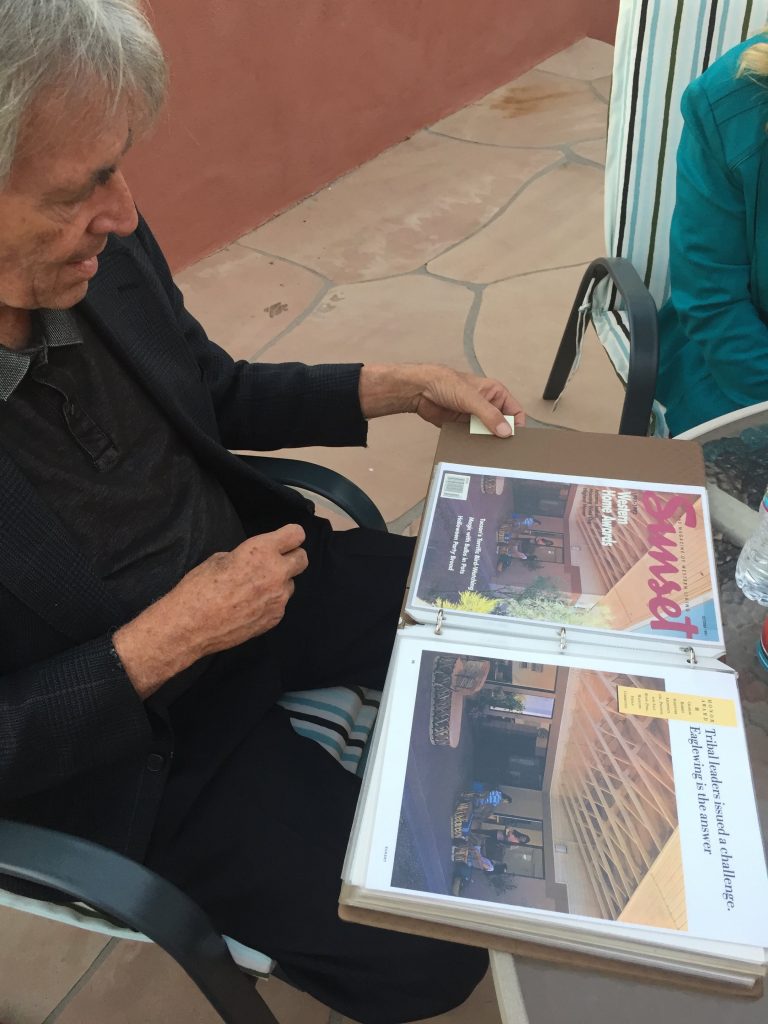

Bespectacled and crowned with a mound of shaggy gray hair, Schniffer carries himself with the gravitas of an esteemed professor. He talks slowly and deliberately; it’s as though each word is a tile he’s delicately setting down to create an ornate mosaic. But he’s never boring, especially on the subject of architecture – an art form that he’s devoted most of his life to.

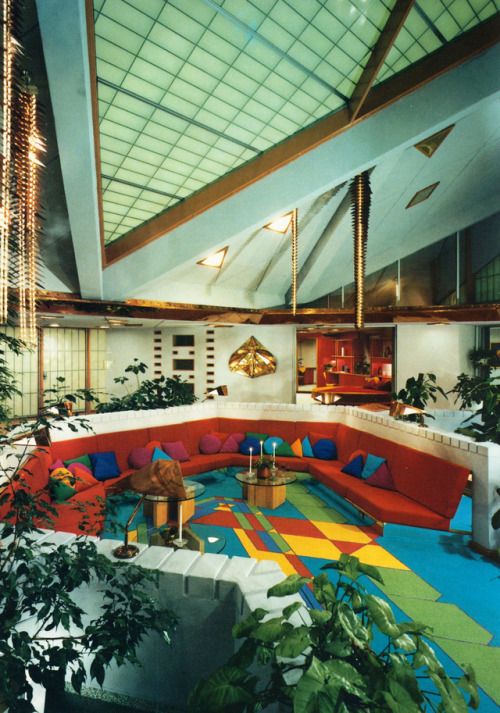

Born in 1948, Schiffner cemented his reputation as an architect with forward-thinking designs like the Floating House in Paradise Valley and the House of the Future in Ahwatukee. The Floating House is a sleek marvel, boasting a flowing sense of space and a negative edge pool that looks like it’s suspended in mid-air. The House of the Future got its name thanks to its sharp geometric design and state-of-the-art automation, which was so radical in 1979 that President Carter was planning on attending the house’s ribbon-cutting before the Iran hostage crisis threw a monkey wrench into his plans.

Son-in-law of the legendary Frank Lloyd Wright, Schiffner shares Wright’s almost evangelical passion for architecture’s ability to add “grace to the landscape.” Schiffner refined his eye as a student at Taliesin. It’s because of that appreciation for beauty that Schiffner is rankled by the bad architecture he sees every day in the Valley.

“Architecture that’s for profit only, devoid of any sense of giving the world beauty,” he says with visible scorn. “If you really took in the horror of what we’re doing to our desert and to our plains and mountains, filling them with this crap – you’d have to put on blinders not to go insane!”

When it comes to defining beauty in architecture, Schiffner has what he calls “an esoteric view” of the subject. “One of the unfortunate situations in America is the preponderance of people who believe that beauty is in the eye of the beholder: ‘I know it when I see it and I like it’. But I insist that beauty exists in spite of the eye of the beholder and is beyond opinion. There are higher forms of beauty that we’re not even aware of, ” says Schiffner.

This notion that forms can possess an objective level of beauty was a view shared by Schiffner’s father-in-law. “Frank Lloyd Wright was designing a home and the wife of his client asked, ‘Where is the hallway where I can put my family photos?’” Schiffner says. “And he said, ‘Oh, you don’t need that, you can can put them on this table over here.’ What he was doing was challenging her: Did she understand the opportunity that was in front of her, to create a Frank Lloyd Wright original? In order to do that, she’d have to rearrange her values. To see the beauty that was beyond herself.”

Schiffner shakes his head. “It didn’t work out, and the house wasn’t built.”

Fortunately, that wasn’t the case with the Schiffner house where he and I are having this conversation. Completed in 1985, the property at 1752 E. Vogel Avenue in Phoenix was a house created in a relative harmony between Schiffner and the original owners. While the architect often talks about beauty as a kind of Platonic ideal, the house on Vogel (which is currently on the market) gives insight into the kind of aesthetic touches and grace notes that Schiffner puts into his work.

Schiffner’s concept for the Vogel house was “bringing the outdoors in.” He accomplished this with carefully placed windows: 652 of them, to be exact. Glass blocks dot the walls around the home, which also features curving walls and teardrop-shaped ceilings. As you wander through its halls, the sense of freedom and ease of motion the house instills is a revelation. It’s a sobering reminder of how confining and rigid it feels when you’re inside an assembly-line house, the kind of place that Schiffner derides as “four walls with a couple of holes for windows.”

To Schiffner, that’s one of the more important questions to ask of any piece of architecture: How does it make you feel? “That’s the question to ask a student: What do you think the architect who designed this building thinks of you?” he says. “How do you feel in here? How do you feel here compared to church?”

These kinds of concerns make Schiffner another idealist in the long train of thought on this subject. Chinese philosophers developed feng shui because of their belief in how a person’s surroundings could radically affect their mind, health, and fortunes. The Romans would consult and give offerings to genius loci, the protective spirits of places. The French Situationists integrated these ideas by creating the practice of psychogeography, which Guy Debord defined as “the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographic environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals.”

Architecture’s ability to influence and shape our being is what makes it such a vital part of our civilization, according to Schiffner. “Architecture is the cure, the solution.” As to how it can be a cure, Schiffner cites the miracle of Medellin, Colombia – a city torn apart by gang violence and drug cartels that was saved by the power of architecture.

“The leadership there, the mayor, drew maps of Medellin,” Schiffner explains. “And where the gangs were most prominent, they’d put in a library. They did a world search to find the best architect and then plunked the library down right where the gang activity was. They did this in several nodes throughout Medellin, and it totally changed the city.”

What Schiffner is describing is almost alchemical in nature – the lead of society is transformed into gold, given the proper ingredients. Even the way he talks about his profession sounds a bit like Paracelsus, the Swiss alchemist who practiced during the German Renaissance: “The architect is in the practice of transforming materials. Architecture is a process of synthesis.”

“The materials, the budget, the terrain, the nuances of the family in the house that you’re designing for – does the husband like to get up early and read the paper while watching the sunrise? Why did they buy this land? Was it for the distant views? The isolation? The surrounding architecture? And so on. Each project that I’ve done has been a totally new facet of the same gem. It’s all about finding relationships.”

The urge to transform and beautify seems to be the driving force behind Schiffner’s latest project: a series of proposals that would give a whole new meaning to the term “organic architecture.” Emboldened by a successful proposal he submitted to the city of Casa Grande involving a large-scale greenhouse garden, Schiffner is imagining a brighter, greener tomorrow for our malls.

“We’re trying now to meet with property owners,” Schiffner says. “All of the malls have enormous parking lots, and hardly any of that space is being used. Now that malls are becoming a thing of the past, we could activate those spaces. We would have a series of elevated glass greenhouses; you’d have the product up above, and you can drive underneath them. All of the parking would become covered parking! And we would capture the CO2 from the parking lot and use it to enhance the growing.”

Schiffner also envisions this type of greenhouse parking becoming a staple for grocery store chains like Safeway and Fry’s. They could have the produce they’re selling inside their stores growing above their patrons’ parked cars. I think back to what he said earlier about how architecture should make you feel something. How much more pleasant would it be to go grocery shopping when you could walk under a canopy of gardens?

“Architects are unique in that we need to think and create in three dimensions,” Schiffner says as the sun sets on Vogel Avenue. Listening to him talk about a world where malls become greenhouses and libraries halt gun violence, I feel as though I’ve only been seeing in two dimensions. Like that tiny patch of quartz on the horizon, Schiffner sees a golden future that most of us are blind to.